The wild turkey (Meleaagris gallopavo) is a species of bird native to North America. There are six subspecies of M. gallopavo, two of which have populations in Canada: the Eastern wild turkey, M. gallopavo silvestris and Merriam’s wild turkey, M. gallopavo merriami. The Eastern wild turkey is native to southern Ontario and Quebec, while Merriam’s wild turkey was introduced to Manitoba in 1958 and to Alberta in 1962. In the 1960s, Merriam’s wild turkey naturally expanded their range from the northwestern United States into southern British Columbia. Today, Merriam’s wild turkey can also be found in Saskatchewan.

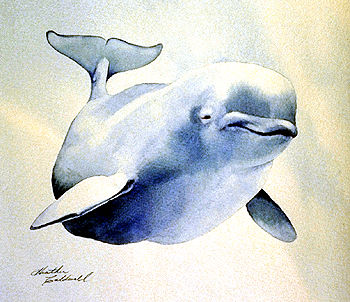

A male Eastern wild turkey in Point Pelee, Ontario.

Description

The wild turkey is a member of the order Galliformes, which includes pheasants, chickens and quails. They are characterized by heavy-set bodies, colourful plumage, and the call males make to attract females, known as a “gobble.”

Wild turkeys are the heaviest of Galliformes. Males weigh between 8.1-13.6 kg, and females between 3.6-6.3 kg. Males are called “toms” or “gobblers” and are much more colourful than females. Their naked heads are coloured in hues of red, blue and white, and their body feathers include shades of dark brown, bronze, copper, chestnut, purple and iridescent green. Their fantail feathers are striped brown, white and black. The tips of their tails are also brown, tan, white or black, depending on the subspecies. When displaying their fantail, males appear almost twice their size. Female turkeys are called “hens.” They do not have fantails, and although they may have the same spectrum of colours as toms, the colours are much duller.

A female Eastern wild turkey in Point Pelee National Park.

Subspecies vary slightly in body size, plumage colours, and the strength of their gobble. Eastern wild turkeys have chestnut banded tail tips and are said to have the strongest gobble of all subspecies. Merriam’s wild turkeys have beige tail tips and rump feathers, and are said to have the weakest gobble.

Reproduction and Development

Mating season takes place between February and June, depending on latitude and climate. Males strut, fan their tails, gobble and dance around. After mating, females search for nesting sites hidden from predators, and they scratch the earth to create shallow depressions to lay their eggs in.

Female Eastern wild turkeys lay on average 10 to 12 eggs per brood, while Merriam’s lay 8 to 12. Hens frequently reposition their eggs in order to make sure all surface areas receive adequate body heat. Wild turkey hatchlings are born fully developed and grow very rapidly. Within the first week, chicks can perform species specific behaviours, and by 14 weeks they’ve developed their distinctive male and female plumage.

Habitat and Diet

This map depicts the combined range for all six subspecies of wild turkey (Meleaagris gallopavo) in Canada and the United States. Eastern wild turkeys (M. gallopavo silvestris) are found in southern Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec, while Merriam’s wild turkey (M. gallopavo merriami) are found in southern British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

Wild turkeys have separate habitats for breeding and non-breeding seasons. During breeding season, wild turkeys prefer open pastures, agriculture fields, areas near streams and rivers, open forest areas and meadows. These areas provide the insects and seeds that form the majority of their diet, especially for growing chicks. During non-breeding season, wild turkeys can be found in open, mature forests of mixed hardwood and softwood where they often like to roost.

Eastern wild turkeys have the largest range of all the Meleaagris gallopavo subspecies. They have adapted to various types of habitats across North America. Merriam’s wild turkeys, on the other hand, prefer pine-oak forests and varying elevations of the Rocky Mountains.

Wild turkeys are opportunistic foragers and eat a variety of items such as nuts, fruits, seeds from grasses and sedges, insects, snails, frogs, salamanders and crayfish. They are generally crepuscular, meaning they forage in early morning and late afternoon.

Relationship With Humans

Wild turkeys were an important source of protein for First Nations throughout North America. Specific peoples who hunted wild turkey include the Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, Ojibwe and Potawatomi. Hunting methods differed from nation to nation; for example, the Huron-Wendat used snares and bows and arrows, while the Haudenosaunee relied on snares. Similarly, methods of preparation also varied. The Potawatomi pickled, then smoked, turkey meat, while other groups roasted, boiled or stewed the birds.

Today, wild turkeys are hunted in the spring and fall in Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia, and in the spring in Quebec and Alberta.

Extirpation and Restoration

When European settlers arrived in North America, they hunted wild turkeys in large numbers. In addition, much of the species’ natural habitat was cleared for farmland. As a result, by 1909, the Eastern wild turkey was extirpated from Canada.

Attempts at restoring wild turkey populations began in the mid-20th century in the United States. By 1976, people reported seeing wild turkeys in southern Quebec; however, it wasn’t until 1984 that planned restoration efforts began in Ontario. As a part of these efforts, in the winter of 1986-87, conservationists in Ontario began trapping wild turkeys and transferring them to other parts of the province. Since the Eastern wild turkey population has been re-established in Ontario, conservation efforts are now focused on maintaining the population while still providing hunting opportunities.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom