The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 was the largest strike in Canadian history (see Strikes and Lockouts). Between 15 May and 25 June 1919, more than 30,000 workers left their jobs (see Work). Factories, shops, transit and city services shut down. The strike resulted in arrests, injuries and the deaths of two protestors. It did not immediately succeed in empowering workers and improving job conditions. But the strike did help unite the working class in Canada (see Labour Organization). Some of its participants helped establish what is now the New Democratic Party.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

This is the full-length entry about the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. For a plain-language summary, please see Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 (Plain-language Summary).

Background

After the First World War, many Canadian workers struggled to make ends meet while employers prospered. Unemployment was high, and there were few jobs for veterans returning from war. Due to inflation, housing and food were hard to afford. Among the hardest hit in Winnipeg were working-class immigrants.

Workers elsewhere in the world were fighting for better treatment. There had been strikes before the successful Russian Revolution in 1917. A growing international workers’ movement called syndicalism sought to bring down capitalism. It inspired western Canadian labour leaders to meet in Calgary in March 1919. There, they discussed the creation of the One Big Union.

Take the quiz!

Test your knowledge of Labour History in Canada by taking this quiz, offered by the Citizenship Challenge! A program of Historica Canada, the Citizenship Challenge invites Canadians to test their national knowledge by taking a mock citizenship exam, as well as other themed quizzes.

Winnipeg General Strike

In Winnipeg, Manitoba, workers in the building and metal trades negotiated with their managers for job improvements. They wanted the right to collective bargaining, better wages and better working conditions. Workers staged several strikes in early May 1919. On 15 May, the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) called a general strike after talks broke down (see also Labour Mediation).

Within hours, almost 30,000 men and women left their jobs. This shut down the city’s privately owned factories, shops and trains. Public employees joined them in solidarity. These included police, firemen, postal workers, telephone and telegraph operators and utilities workers.

The Central Strike Committee co-ordinated the strike. Its members were elected from each of the unions linked to the WTLC. The strike committee bargained with employers on behalf of the workers. It also ensured that essential services continued in Winnipeg.

Did you know?

Labour activist Helen Armstrong, nicknamed “Ma,” was one of only two women among some 50 men on the Central Strike Committee. During the strike, she established the Labour Café, which provided women strikers with three free meals a day. This was an essential service for those who lost wages due to the strike. The cafe also welcomed men but encouraged them to pay or make a donation. It reportedly served 1,200 to 1,500 meals a day.

Opposition

The Citizens’ Committee of 1,000 quickly formed to organize opposition to the strike. It included Winnipeg’s most influential business leaders and politicians. This committee did not seriously consider the strikers’ demands. It called the strike a revolutionary plot led by a small group of “alien scum.” Winnipeg’s leading newspapers took this view, too. In reality, there was little evidence that the strike was started by Bolsheviks and immigrants from eastern Europe. But the Citizens’ Committee used these unproven charges to block any efforts to appease workers.

Government Response

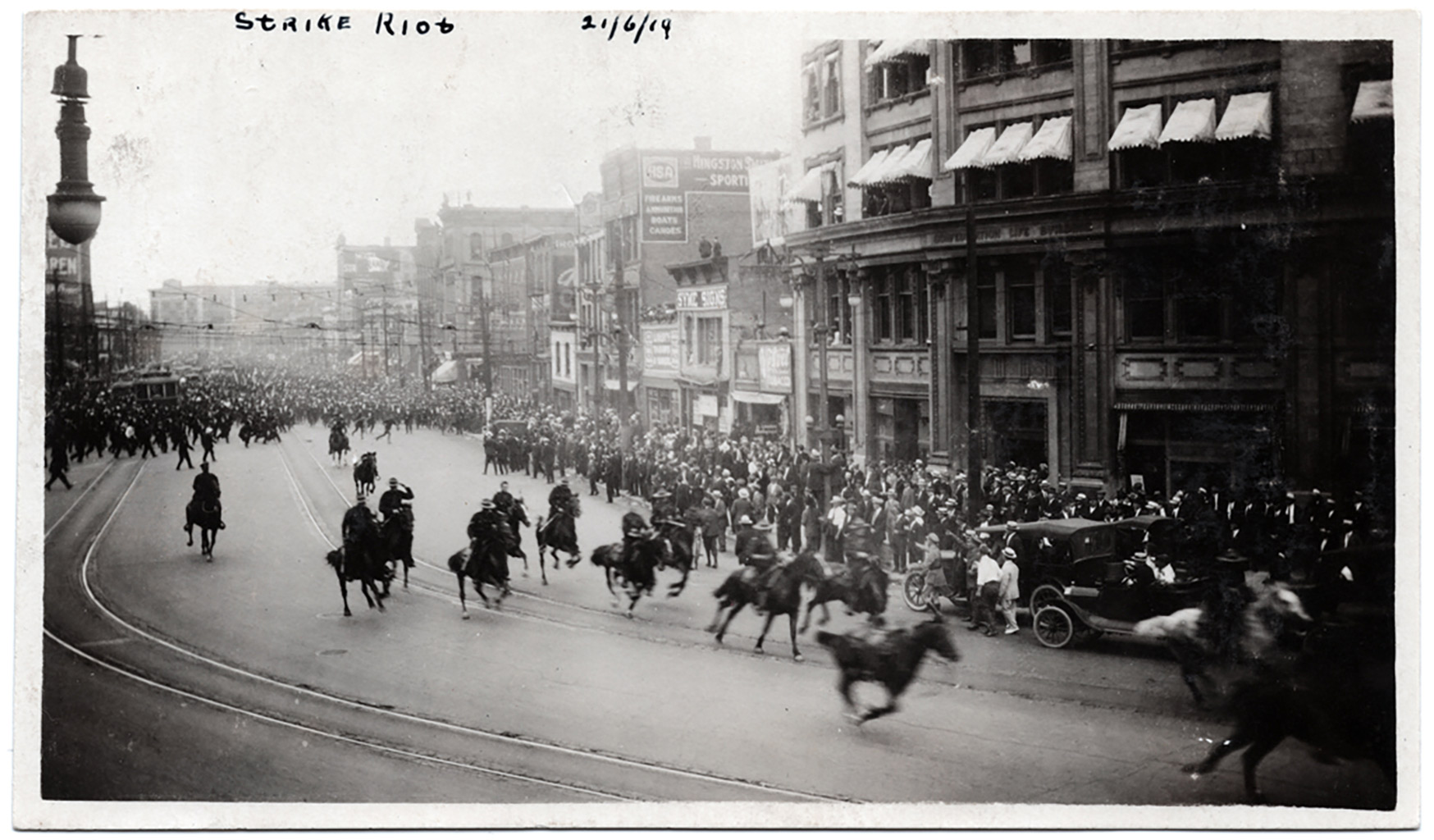

Photo of mounted troops galloping around a bend in the road at Main Street and Market Avenue on Bloody Saturday, 21 June 1919.

The federal government decided to step in. It was afraid the strike would spark conflicts in other cities. Soon after the strike began, two Cabinet ministers met with the Citizens’ Committee in Winnipeg. These officials were Senator Gideon Robertson, minister of labour, and Arthur Meighen, minister of the interior and acting minister of justice. Robertson and Meighen refused to meet with the Central Strike Committee.

On the Citizens’ Committee’s advice, the federal government swiftly supported the employers. It threatened to fire federal workers unless they returned to work immediately. Parliament changed the Immigration Act so that British-born immigrants could be deported. It also broadened the Criminal Code’s definition of sedition (see Criminal Code, Section 98).

On 17 June, the government arrested 10 leaders of the Central Strike Committee and two members of the One Big Union. Four days later, strikers held a silent parade in support of the arrested leaders. At City Hall, the crowd began to vandalize a streetcar. The Royal North-West Mounted Police charged at the protestors, beating them with clubs and firing bullets. The violence injured about 30 people and killed two. Known as Bloody Saturday, the day ended with federal troops occupying the city’s streets.

Police released six of the labour leaders. However, they arrested Fred Dixon and J.S. Woodsworth, editors of the daily Strike Bulletin.

The combined power of the government and employers crushed the strike. On 25 June, the strike committee announced a return to work and set the strike’s official end for the next morning.

Seven strike leaders were eventually convicted of planning to topple the government. They received jail terms of six months to two years. The charges against Woodsworth were dropped.

Importance

In the short term, the Winnipeg General Strike did not achieve gains for workers. It left a legacy of bitterness and controversy among organized labour groups across Canada. But in uniting workers around common goals, it also helped bridge divides between them. In Winnipeg, for example, Canadian-born workers walked out with immigrants from Britain and mainland Europe.

Did you know?

After the First World War, immigrants from central, southern and eastern Europe were often viewed with suspicion. In the early 1920s, the Canadian government labelled them a “non-preferred” category. (See also Prejudice and Discrimination; Immigration Policy in Canada.)

The general strike sparked more unionism and activism. Workers in cities from Amherst, Nova Scotia to Victoria, British Columbia, walked out in support of the Winnipeg strikers. Some strike leaders, including J.S. Woodsworth, were elected to government. Woodsworth and other former strikers helped found the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. This socialist labour party later became the New Democratic Party.

It took three decades after the Winnipeg General Strike for employers to recognize Canadian workers’ unions and grant collective bargaining rights.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom