Winter Characteristics

Meteorologists and climatologists in the Northern Hemisphere generally consider December, January and February as the winter months. In Canada, however, the length of winter varies by region and by severity because of the country's latitudinal range.

In most of Canada, winter is marked by snow, ice, blizzards, wind and the hazards of wind chill. Extreme weather during Canadian winters seems the norm, rather than an exception. The coldest recorded temperature in North America occurred in Snag, Yukon, on 3 February 1947, when the temperature reached a bone-chilling -63˚C.

Human Adaptations to Winter

The conditions of winter have required the development of many adaptations, the first of which came from the country's Indigenous peoples, who devised many of their adaptations by observing animals in winter. Some of these adaptations, such as the toboggan, kayak and snowshoes, facilitated travel and exploration in the early days of the country, and have since been incorporated into Canadian leisure activities. Habitation presented challenges for the earliest peoples in winter, solved most ingeniously by the Inuit who developed a way to build igloos out of snow for their winter dwellings.

Transportation is a particular concern in Canada because of the country's vast geography; in winter, roads and highways are an even more crucial aspect of daily life. The first winter roads were frozen waterways used by the First Nations, whose example was followed by explorers, settlers and soldiers. The first roads in Canada were little more than cleared paths and so rough that most people preferred to travel by horseback or on foot than by any type of conveyance. Some roads were marginally improved by planking with logs laid side by side. These "corduroy" roads provided important inland transportation, especially in winter when uncomfortable wagons and carriages traded their wheels for runners.

Winter was an impediment to travel even by rail, and necessitated the invention of the snow plough. In the 19th century, as the railways opened the West to settlement, winter proved a harsh and unyielding foe. Thousands of men were hired to remove snow from the tracks with shovels. In 1869, a Toronto dentist, J.W. Elliott, designed the first rotary snowplough. Another Canadian, Orange Jull, improved his design. The Elliott-Jull snowplough became standard equipment on trains in North America, allowing them to operate under the harshest conditions and putting fewer men at risk during winter rail maintenance.

Attitudes Toward Winter

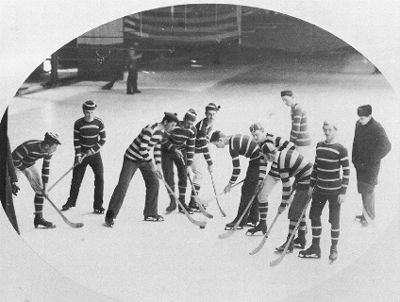

Winter may be considered an unnatural environment for humans, but Canadians seem to revel in the hardiness that allows them to weather, if not actually embrace, their harsh winter climate, so much so that winter may be said to be part of Canadian identity. Across the country, winter does not keep Canadians indoors. People take part in winter sports such as hockey, alpine and cross-country skiing, snowboarding, skating, snowshoeing, curling and snowmobiling.

Canadian winter is a time of seasonal celebrations such as: the famous Carnaval de Québec in Québec City, which includes a hotel made of ice; Winterfest in Calgary; the WinterStart Festival in Banff, Alberta; and Winterlude in Ottawa. Many events include lights to brighten the long nights, including: Toronto's Cavalcade of Lights; Montreal's High Lights Festival; and Winter Festival of Lights celebrations in Vancouver, Airdrie, Alberta, and Niagara Falls. Typical winter festival activities include sleigh rides, cross-country ski races, skating, snow and ice sculpting, fireworks, bonfires, and plenty of food and hot drinks.

The northern territories are most closely aligned culturally with winter by virtue of having so much of it. Winter festivals in the North include: the Snowking’s Winter Festival in Yellowknife, with its castle carved from snow; the Yellowknife Long John Jamboree featuring dogsled derbies; the K’amba Carnival and Polar Pond Hockey Tournament in Hay River, Northwest Territories; and the Top of the World Ski Loppet in Inuvik, Northwest Territories. The Arctic Winter Games were initiated in 1970 to give northern athletes the opportunity to train and compete in a range of sports.

Winter Folklore

A country with so much winter is bound to have some associated folklore, especially among Indigenous peoples. Among Canada's winter folklore is the Inuit myth of the ice worm, which is called Sikusi, and is said to melt igloos. The ghost of a trapper, sentenced to atone for his many sins by helping lost travellers, is said to roam the wilds of Labrador on a sleigh pulled by white huskies. Perhaps the most enduring piece of folklore, which may be better described as a misunderstanding, is the idea that the Inuit either have, or don't have, many words for snow; both ideas convey an element of folklore.

The argument in favour of this linguistic myth claims that Inuit language groups add suffixes to words to express the same concepts expressed in English and many other languages by means of compound words or phrases, but that there are no more root words that refer to snow than in other languages (see Inuktitut; Inuktitut Words for Snow and Ice). However, anthropologists with expertise about Arctic Indigenous peoples speak of the diversity of Inuit terms related to ice and snow, but it is unclear if these can truly be considered as distinct "words" from a linguistic point of view. What is certain is that the Inuit describe ice and snow in ways that help them understand and deal with the environment in which they live and travel. Snow and ice are very important and often dangerous features of their cultural landscape and must be understood for survival. Precise communication about ice and snow features or conditions is vital and accounts for the diversity of terms used to describe them.

By the time Groundhog Day arrives (2 February), most Canadians are looking for signs of spring and may be willing to believe the folklore surrounding the groundhog's appearance to look for its shadow. Unfortunately, February is often the worst month of winter, with several winter records having been set in that month, including: a deadly snowstorm in St. John's in 1959; an ice storm in 1961 that left parts of Montréal without power for a week; a 1979 blizzard that isolated Iqaluit, Nunavut, for 10 days; a blizzard in 1982 that marooned Prince Edward Island for a week; the Ocean Ranger disaster on 15 February 1982; and the greatest single-day snowfall of 145 cm in Tahtsa Lake, British Columbia, on 11 February 1999.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom