Origin of Zee, Zed

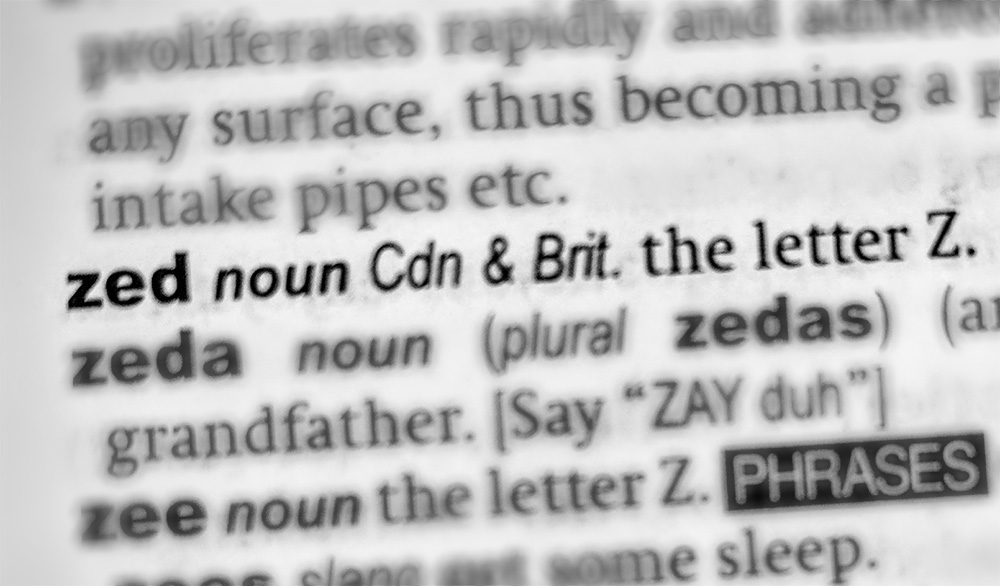

According to The Canadian Oxford Dictionary (2nd edition), the word zed is derived from the French word for the same letter, zède, as well as from the Latin and Greek word for the letter zeta. There were many historic names for the letter Z, including zad, zard, ezed, ezod, izod, izzard and uzzard. In fact, Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) includes the entry: “zed, more commonly izzard or uzzard” (see Early Dictionaries). The earliest citation for zed dates to 15th-century Middle English: “zed, which is the laste lettre of the a-b-c.”

The pronunciation zee is a 17th-century variant of zed. The earliest citation is from a 1677 language textbook, A New Spelling Book by Thomas Lye, a Nonconformist minister and teacher in London, England. It’s thought that zee was last used in England during the late 17th century; however, usage is difficult to trace, because pronunciations for letters were not often written down. Regardless, zee made its way to the British colonies in North America.

While different pronunciations for the letter were used in the United States, the famed American lexicographer Noah Webster wrote in An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) that, “It is pronounced zee.” The motivation behind Americans adopting zee is debated. Some argue that Americans sought to distinguish themselves from the British, particularly as they fought for their independence (see American Revolution). Others argue that zee follows the rhyme pattern of the “Alphabet Song” — copyrighted in Boston in 1835 — making the song, and the alphabet, easier to learn. Zee became the American standard.

Why Do Canadians Say Zed?

While British and American English have distinct vocabularies, Canadian English vocabulary is informed by both. For the most part, however, Canadian English follows the American influence, with Canadians preferring flashlight to torch and diaper to nappy, for example. Zed is perhaps the most iconic instance of Canadians preferring the British term to the American. But that was not always the case.

During the Victorian era (1837–1901), both zee and zed were used in present-day Ontario; however, promoters of “the Queen’s English” found such examples of North American English to be vulgar or even rude. Still, evidence suggests that children were taught to say zee in school. Canadian linguist J.K. Chambers cites an 1846 letter to the editor of the Kingston Herald in which a man called Harris complains that, “The instructor of youth, who when engaged in teaching the elements of the English language, direct them to call that letter ze, instead of zed, are teaching them error.” William Canniff, an amateur historian and contemporary, noted “the presence of American teachers and school books” — including a spelling book by Noah Webster — through which Canadian students learned the “peculiarities of American spelling and pronunciation.” The degree to which American teachers and textbooks influenced Canadian English is debateable, as British textbooks were more popular. In the end, education reform led by Egerton Ryerson in the 1840s standardized school textbooks in anglophone Canada West (Ontario), settling on British books and removing American textbooks from classrooms (see Curriculum Development). Eventually, zed gained preference over zee.

According to a 1974 linguistic study by M.H. Scargill, zed was preferred by English-speakers across Canada — except in Newfoundland. Between 72 and 79 per cent of Canadians said zed, while 11 to 15 per cent said zee; the remaining respondents said either zed or zee. Since then, preference for zee has been on the rise, while zed has been on the decline. However, the change has been far less pronounced than in other examples: change in preference for the term couch over chesterfield, or gutters over eavestroughs, has been more acute. According to the North American Regional Vocabulary Survey carried out by linguist Charles Boberg from 1999 to 2007, 70 per cent of Canadians now say zed and 28 per cent say zee.

The Student’s Oxford Canadian Dictionary (2nd edition) includes entries for both zed and zee but says:

Both “zed” and “zee” are acceptable pronunciations for the letter Z in Canada, though “zed” is much more common. Be warned, however, that some people feel very strongly that it is a betrayal of Canadian nationality to say “zee” and you may incur their wrath if you do so.

The Gage Canadian Dictionary includes an entry for zed — though not for zee.

The Rise of Zee

According to Boberg, “Canadians who do not wish to appear American” insist on zed; according to Chambers, use of zee, particularly in southern Ontario, is stigmatized. According to both linguists, zed is an iconic example of the small ways in which Canadians resist American linguistic influence and maintain autonomy (see Canadian Identity and Language). However, between 1972 and the mid-2000s, use of zed among students dropped by 11–15 per cent to stand at 61 per cent, while use of zee increased by over 20 per cent to stand at 34 per cent.

Changes in the way people speak as they mature have lessened the rise of zee and may continue to do so. A series of linguistic studies in southern Ontario found that while a higher proportion of young people say zee — likely because they learned it from the “Alphabet Song” or Sesame Street, an American TV show — they change preference to zed in later stages of life. It’s argued that such a shift is a cultural marker of maturity.

Popular Culture

Zany Dr. Zed is a character created by scientist and children’s author Gordon Penrose. Dr. Zed appeared in the children’s magazines OWL and chickaDEE as well as in a series of science activity books published from the late 1970s to the 2000s.

ZeD was a late-night arts and culture show on CBC TV that ran from 2002 to 2006. The show featured independent and sometimes viewer-submitted content, including short films and documentaries, animation and music. Viewers could submit content to the show through ZeD’s website.

Zeds Dead is an electronic music duo from Toronto that formed in 2009. Their name is actually a reference to a line in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994).

Zed was a Cirque du Soleil production staged in Japan from 2008 to 2011.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom