Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern Woodlands

Eastern Woodlands Indigenous peoples belong to two unrelated language families, Iroquoian and Algonquian. It is important to note that while Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) peoples form part of the Iroquoian language group, they do not comprise the entirety of the group. The same is true for the Algonquin and the Algonquian language group.

Iroquoian-speaking peoples in this area include the Erie (south of Lake Erie), Neutral (Grand River–Niagara River area), Wenro (east of Niagara River), Haudenosaunee or Six Nations (including Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk and Tuscarora), Wendat-Huron (St.Lawrence River Valley in the 1500s, Wendake or Huronia in the 1600s, which stretched from Georgian Bay to Lake Ontario), Petun (south and southwest of Georgian Bay) and St. Lawrence Iroquoians (present-day Montréal to Québec City).

Algonquian-speaking peoples in the Eastern Woodlands include the Ojibwe (eastern Lake Superior to northeastern Georgian Bay), Odawa (Manitoulin Island and Bruce Peninsula), Nipissing (Lake Nipissing area), Algonquin (Ottawa River and tributaries), Abenaki (present-day Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, New Brunswick and southeastern Québec), Wolastoqiyik (formerly known as Maliseet) (St. John River in western New Brunswick, northeastern Maine to Québec) and Mi’kmaq (Gaspé Peninsula, and what is now New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia).

Geography

The Eastern Woodlands is a large region that stretches from the northeastern coast of present-day United States and the Maritimes to west of the Great Lakes. It extends southwest to present-day Illinois and east to coastal North Carolina. The deciduous forests of southern Ontario (see Forest Regions), the St. Lawrence lowlands and coastal Maritime provinces phase north into the mixed deciduous-coniferous canopy of the Canadian Shield in the west and the Appalachian uplands in the east. Except in the Maritime provinces, the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence watershed provided access to water transportation to all Eastern Woodlands peoples. Climate and soil conditions allowed peoples south of upland regions to grow corn, beans and squash (known as the Three Sisters); the largest portion of many Eastern Woodlands peoples’ diets consisted of produce from their fields.

Traditional Territory

Iroquoian-speaking peoples in the Eastern Woodlands generally occupied much of what is now southern Ontario, northern Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York, and the St. Lawrence Valley as far east as the present-day Québec City area. Algonquian-speaking groups extended from Lake Superior north of Lake Huron to the Ottawa Valley, and east through present-day New England and the Maritime provinces.

Traditional Life

Food

Iroquoian-speaking peoples relied primarily on cultivated corn, beans and squash. Fishing, hunting and gathering supplemented these domestic crops. White-tailed deer were one of the most important game animals except in the north, where moose were the staples. Some coastal peoples hunted seals as well as freshwater fish, eels, molluscs and crustaceans. Waterfowl and land birds were seasonally important in some areas. Fur bearers, especially beaver, were significant to trade-based economies. Peoples in the area gathered and ate a variety of berries, nuts, tubers and plants; and some groups harvested maple and birch sap. While Iroquoian women planted and harvested, men were made to clear the forest for farming.

Among most Algonquian peoples, horticulture for subsistence was largely marginal, except for the cultivation of wild rice in some communities. Odawa, Algonquin, Mi’kmaq and Abenaki peoples planted few crops. On the other hand, farming was important to the Wolastoqiyik economy, especially the growing of corn. The Ojibwe relied on wild rice, which was harvested in the late summer, and may have been responsible for its spread outside the lands where it was typically found. The Nipissing did some cultivating of corn, but they also traded fish and furs for Wendat corn. Hunting and fishing provided the bulk of sustenance for Algonquian peoples. They hunted deer, bear, moose and caribou, and, where available, seals, porpoises and whales. In hunting they used bows, arrows, lances, traps, snares and deadfalls, and used hooks, weirs, leisters and nets to fish. Meat was either boiled or roasted for immediate consumption or smoke-dried for future use. In the Great Lakes area, Algonquian peoples also collected maple or birch sap in the early spring.

The enduring presence of settler-colonial political and social frameworks brought about considerable culture change among all Eastern Woodlands groups. Hunting, gathering and fishing have become marginal subsistence activities except among some nations, for whom fishing has remained a significant source of income, but not without its challenges. Agricultural practices declined as reserve populations grew, lands were partitioned and new employment opportunities arose.

Dwellings

Crop storage among the Iroquoian peoples permitted sedentary (permanent) and fenced-in settlements ranging from small hamlets with a few families to towns where as many as 2,000 persons resided. Population density was high among the Wendat. Although estimates vary, there may have been from 70,000 to 90,000 northern Iroquoians at the time of contact. A typical village contained a large number of elm- or cedar-bark longhouses.

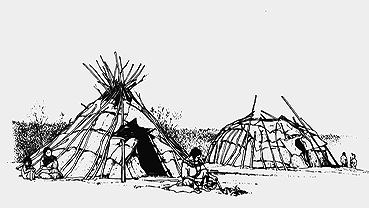

Seasonal activities among the Algonquians tended to inhibit a strictly sedentary existence, although the abundance of certain food, especially fish and some horticulture, permitted a greater degree of sedentation than among Subarctic peoples farther north. Dwellings were smaller and less permanent than among Iroquoians, varying from conical birchbark tipis to domed wigwams or rectangular structures that housed several families. Village size varied seasonally, with the largest population concentrations generally occurring in summer.

Transportation

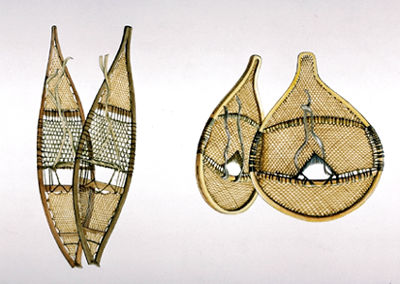

The Iroquoians travelled mainly on land or in elm-bark or birchbark canoes. The Algonquians made slender birchbark canoes (the Mi’kmaq used caribou-skin canoes) and in winter used snowshoes, sleds and toboggans. Trade and visiting appear to have been common activities among neighbouring Algonquian peoples. They also traded with Iroquoian peoples, importing corn and fish nets from the Wendat, for example.

Clothing

Clothing of the Eastern Woodlands Indigenous peoples was made of animal skins and furs. While the men hunted animals for hides (as well as for meat), women were responsible for tanning the skins and creating the clothing. Women also decorated the clothing with beads, quills and other natural products. Typical clothing for the people of the Eastern Woodlands included robes, breechcloths, leggings and skirts. For footwear, people wore moccasins, which are slipper-like shoes made out of animal hide.

Social Organization

Prior to contact, the largest political unit among most Eastern Woodlands Algonquian peoples appeared to be the band-village, a community consisting of various bands. Each band or band-village possessed at least one chief, whose position was usually hereditary within the male line. Patrilineal groups designated by an animal totem seem to have been characteristic of Eastern Woodlands Algonquian peoples. Village-band territories were not strictly demarcated, and all members had access to basic subsistence resources.

In Iroquoian society, longhouses sheltered several related families. Residence in these households was matrilocal (upon marriage a man would move into his wife’s longhouse). As well, descent, inheritance and succession followed the female line. One or more households formed a matrilineage. Several lineages composed an exogamous clan — where individuals must marry outside the social group — designated by a particular totem emblem. Clan mates among the Haudenosaunee, regardless of village or community affiliation, considered themselves to be siblings. Nations were composed of 3 to 10 clans whose members were scattered in several villages. Among some groups, clans were united into moieties (kinship groups).

Most Iroquoian peoples possessed both civil chiefs and war chiefs. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy had a council of about 50 permanent and hereditary offices, which have survived in modified form to the present. Condolence ceremonies commemorated deceased confederacy chiefs, bestowing upon their successors the honorary names associated with the office. The Wendat had a similar political system.

Culture and Art

Intricate beadwork and quillwork is one feature of Eastern Woodlands art. Women used feathers, porcupine quills, shells, dyes and similar items to adorn their family’s clothing, moccasins and belongings. Iroquoian peoples often decorated clan symbols on their longhouses.

Beadwork was sometimes more than decorative; it could hold political meaning. Eastern Woodlands peoples created wampum, tubular purple and white beads made from shells used for ornamental, ceremonial, diplomatic and commercial purposes. In some early treaties, wampum belts featured the major tenets of the agreement. To accept a wampum belt in formal council was to agree to adhere to the principles embodied in its woven design. The wampum thereafter served to help perpetuate the memory of the treaty.

In some Eastern Woodlands cultures, art was also expressed on the body. Tattooing of the face and body was common for both men and women. These tattoos held symbolic significance and could showcase a person’s heritage and clan identity.

A noteworthy art form of the Haudenosaunee is the False Faces, wooden masks with metal eyes and, sometimes, horsehair that were carved by men for use in curing ceremonies (see False Face Society).

A revitalization of certain aspects of traditional cultures, including languages, arts, crafts, dances and rituals, as well as a greater political awareness, has served to reinforce identity and esteem after more than three centuries of cultural erosion by colonialists.

In contemporary art, the Woodland school of art refers to the colourful and pictographic paintings of artists such as Norval Morrisseau, Daphne Odjig, Jackson Beardy and Alex Janvier. Featuring supernatural beings, animals or people, this art expresses Indigenous identity and culture (see Indigenous Art in Canada and Contemporary Indigenous Art in Canada).

Language

Iroquoian languages belong to two branches, a southern one composed of Cherokee, and a northern branch that includes the Erie, Neutral, Wenro, Haudenosaunee, Wendat, Petun and St. Lawrence Iroquoians. The languages of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, the Wendat, Petun and Neutral are all extinct. Efforts are being made to bring back the Wendat language. The six Iroquoian languages spoken in Canada today (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora) moved with their people from New York State after the American Revolution. These languages are still spoken today, but they are endangered (see Indigenous Languages in Canada).

Within the Eastern Woodlands, there are two branches of the Algonquian family, Central Algonquian (Ojibwe, Odawa, Nipissing and Algonquin) and Eastern Algonquian (Abenaki, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet). Languages within each branch show a high degree of mutual intelligibility, with the Central Algonquian forming dialect chains.

Religion and Spirituality

The Haudenosaunee had a number of medicine societies focused on healing, the best known being the False Face Society. During ceremonies, members wore elaborately carved wooden masks. The Haudenosaunee also practised the Longhouse Religion, a blend of ancient Indigenous traditions and innovations introduced by the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake.

Algonquian peoples practiced Midewiwin (Grand Medicine Society). Once widespread, the Midewiwin became less prevalent after the arrival of Europeans in the 18th and 19th centuries. Today, the largest Midewiwin societies are found in parts of Ontario, Manitoba, Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota.

Generally speaking, Indigenous peoples in the Eastern Woodlands possessed religious specialists known as shamans. Among the Algonquian, the shaman performed magical rites to ward off evil spirits, such as the Windigo, and assisted in locating game. Shamans in Iroquoian communities performed similar roles, ensuring the spiritual and physical well-being of their people. Eastern Woodlands peoples and their shamans engaged in healing practices and in seasonal rituals often associated with crop harvests and periodic feasts. The Wendat, for example, held elaborate Feasts of the Dead, usually at the time when villages were to be moved to new locations. The bones of dead relatives were gathered and placed in mass graves with personal items. Algonquian peoples also held Feasts of the Dead, although they were not identical to those of the Wendat. During the 17th century, these feasts attracted large numbers of people, often from several nations.

Vision quests associated with the acquisition of a personal supernatural guardian existed among Eastern Woodlands cultures. Generally speaking, young males would venture out alone into the wilderness with no food or water and wait for a spirit guide to reveal to them great knowledge. In some nations, such as the Odawa and Menominee, young girls also participated. Once the adolescent performed the quest, they returned to their village an enlightened adult. Some Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands still participate in vision quests (see Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples).

Contact with Europeans and Colonization

Euro-Indigenous Relations Prior to 1763

Although the Norse made sporadic visits to the Arctic and eastern seaboard between the 10th and 14th centuries, major European influences began when fishermen to the Grand Banks started trading for furs in the early 16th century just prior to Jacques Cartier’s contacts with Mi’kmaq and St. Lawrence Iroquoians in 1534–35. During the late 16th century, the fur trade expanded to involve, either directly or indirectly, most Eastern Woodlands peoples. During this period, the St. Lawrence Iroquoians disappeared from their homelands and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy gained prominence.

By the early 17th century, there had been European settlements on Sable Island (temporary), at Tadoussac, briefly on Saint Croix Island in present-day Maine and at Port-Royal in the Annapolis Valley. In 1609, Henry Hudson explored the coast of what became New England and the river named after him, while Samuel de Champlain accompanied an Algonquin, Innu and Wendat war party against the Mohawk near Lake Champlain, an event that marked the beginning of European participation in inter-tribal hostilities that lasted for a century.

By 1626, when the Dutch established New Amsterdam (New York City), intensive trade had largely exterminated fur bearing animals along the Atlantic coast. During the first half of the 17th century, epidemics brought on by European diseases, as well as warfare, drastically reduced Indigenous populations. Meanwhile, new trade relationships with Europeans disrupted the subsistence cycles of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. A variety of trade items replaced Indigenous equivalents, resulting in dependency relationships, and new forms of territoriality and leadership.

In New England, the Pequot War (1636-7) and King Philip’s War (1675–76) decimated the Indigenous population and effectively removed their ability to oppose European settlement. Some Abenaki people moved to St. Francis near the St. Lawrence after about 1675. In the Great Lakes area, the Haudenosaunee intensified their attack on other Iroquoian-speaking peoples and Algonquian groups during the 1640s and 1650s, forcing many to flee their homelands (see Iroquois Wars). Remnant groups of Wendat and Petun peoples (some sources also include the Neutral and Erie) fled west and became known as Wyandot. One group settled at Lorette (or Loretteville) near Québec City, becoming the Huron-Wendat. The Haudenosaunee, their population reduced by warfare and disease, replenished numbers by adopting war captives and refugees.

By the late 17th century, Haudenosaunee power was in flux. Ojibwe and Algonquin peoples moved into present-day southern Ontario; their descendants continue to occupy reserves there today. In 1722, the Haudenosaunee accepted the Tuscarora, a northern Iroquoian–speaking people who had fled from what is now North Carolina, into their confederacy. Following this addition, the confederacy became known as the Six Nations.

Throughout the first half of the 18th century, most Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Eastern Woodlands were allied with the French and traded furs in exchange for European commodities. Except for a group of Mohawk who had settled near Montréal, the majority of the Haudenosaunee were allied with the British.

Indigenous-British Relations, 1763 to 1867

After the French and Indian War (1754–1763) (see Seven Years War) and the fall of New France to the British, a loose coalition of nations including the Odawa and Ojibwe became displeased with the new regime’s policies, which included the appropriation of land, the crushing of any opposition by force and the end of symbolic gift exchanges. In 1763, Odawa chief Obwandiyag (known as Pontiac in English) led his group of Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi and some Wyandot to lay siege to Fort Detroit. His allies captured Fort Michilimackinac and war raged throughout the region, but the alliance quickly faltered. Pontiac agreed to peace in 1766. The incident, known as Pontiac’s War, demonstrated Indigenous peoples’ continued struggle for autonomy, and influenced the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which recognized Indigenous territorial rights and laid the foundation for future treaty negotiations. In practice, the Proclamation did not apply to Maritime colonies, and therefore, colonial administrators in these areas felt empowered to seize lands and establish reserves without treaty negotiations.

Most Algonquian-speaking peoples were allied with the British during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), but the struggle split the loyalties of the Haudenosaunee in New York State, many of whom subsequently moved to lands granted to them by the British in what is now southern Ontario (see Haldimand Proclamation). Members of all the six nations in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy settled along the Grand River, and some Mohawk settled at the Bay of Quinte. Land cessions, a growing economic dependency on European colonists and general demoralization stimulated a revitalization movement in 1799 that was led by the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake. The new Longhouse Religion (also known as the Handsome Lake Religion) spread to other Haudenosaunee communities in the United States and Canada. Handsome Lake and Pontiac are often seen as early leaders of Indigenous self-determination in the “Pan-Indian” movement.

After the War of 1812, some Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi moved from the United States to the Georgian Bay area and a portion of the Oneida settled on the Thames River. During the first half of the 19th century, the colonial government established reserves for Algonquian-speaking peoples around Georgian Bay; and the Robinson-Huron and Robinson-Superior treaties of 1850 secured large tracts of land north of lakes Superior and Huron for the government. In the Atlantic provinces, the colonial government, not bound by the terms of the Royal Proclamation, established some 60 Mi’kmaq communities.

Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian Government

As European settlements throughout the Eastern Woodlands grew larger and more numerous, the hunting and gathering lifestyle of Algonquian and Iroquoian speakers fell increasingly under threat. Horticulture, sometimes the result of missionary influences, supplemented a diet that came to include stored foods as well as locally obtained fish and game. Some Indigenous peoples found employment in the resource industry, working in lumber, mining and the fur trade or as part-time labourers.

As settler dominance over the resource industry grew, Indigenous peoples in the Eastern Woodlands became increasingly marginalized, and were often relegated to poorly serviced and often remote reserve communities. The introduction of Christian residential schools further exacerbated culture loss, removing children from their homes and language. At such schools, students suffered abuse and neglect, engendering further cultural assimilation in their home communities. Deprived of traditional skills and suffering under the weight of cultural loss, reserve communities grew increasingly dependent on government sources of economic support. Lack of employment opportunities and inadequate training resulted in poverty on most reserves that were not situated near large urban centres.

The Indian Act, enacted in 1876 as a combination of the Gradual Enfranchisement and Gradual Civilization Acts, placed reserve councils under the control of the federal government. Under these terms, the government could replace traditional council systems with elected models that aligned more closely to assimilative goals. Many reserve communities resisted these changes. On the Six Nations reserve, the government imposed an elected council structure in 1924, but residents were, and continue to be, largely unsupportive of the system; the traditional council model continues to function in opposition to the government sanctioned one. By the 20th century, many Eastern Woodlands Indigenous peoples had adopted Christianity — among some, only in name — the result of extensive missionary work in the field of education. Many Haudenosaunee continued to practise the Longhouse Religion of Handsome Lake.

Following the Great Depression of the 1930s, many Indigenous peoples began moving to urban centres in Canada and the United States to work. The 1794 Jay’s Treaty allows Indigenous peoples in Canada to travel freely into the United States for work, study or residence. After about 1960, government-sponsored job programs on reserves and community-led revitalization of arts and crafts practices helped to lessen economic dependency in some communities.

Contemporary Life

The Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands have been involved in Canada-wide and international campaigns to protect Indigenous rights (see Idle No More) as well as community-specific causes, including the negotiation of modern-day treaties and self-government. For example, in October 2016, the Algonquins of Ontario signed a land claim agreement-in-principle (i.e., a step towards a final contract) with the Canadian and Ontario governments that covers 36,000 km² of land in eastern Ontario. While the final details of what will be Ontario’s first modern treaty may take years to ratify, it remains an historic agreement — one that has taken 26 years to negotiate.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom