Origins

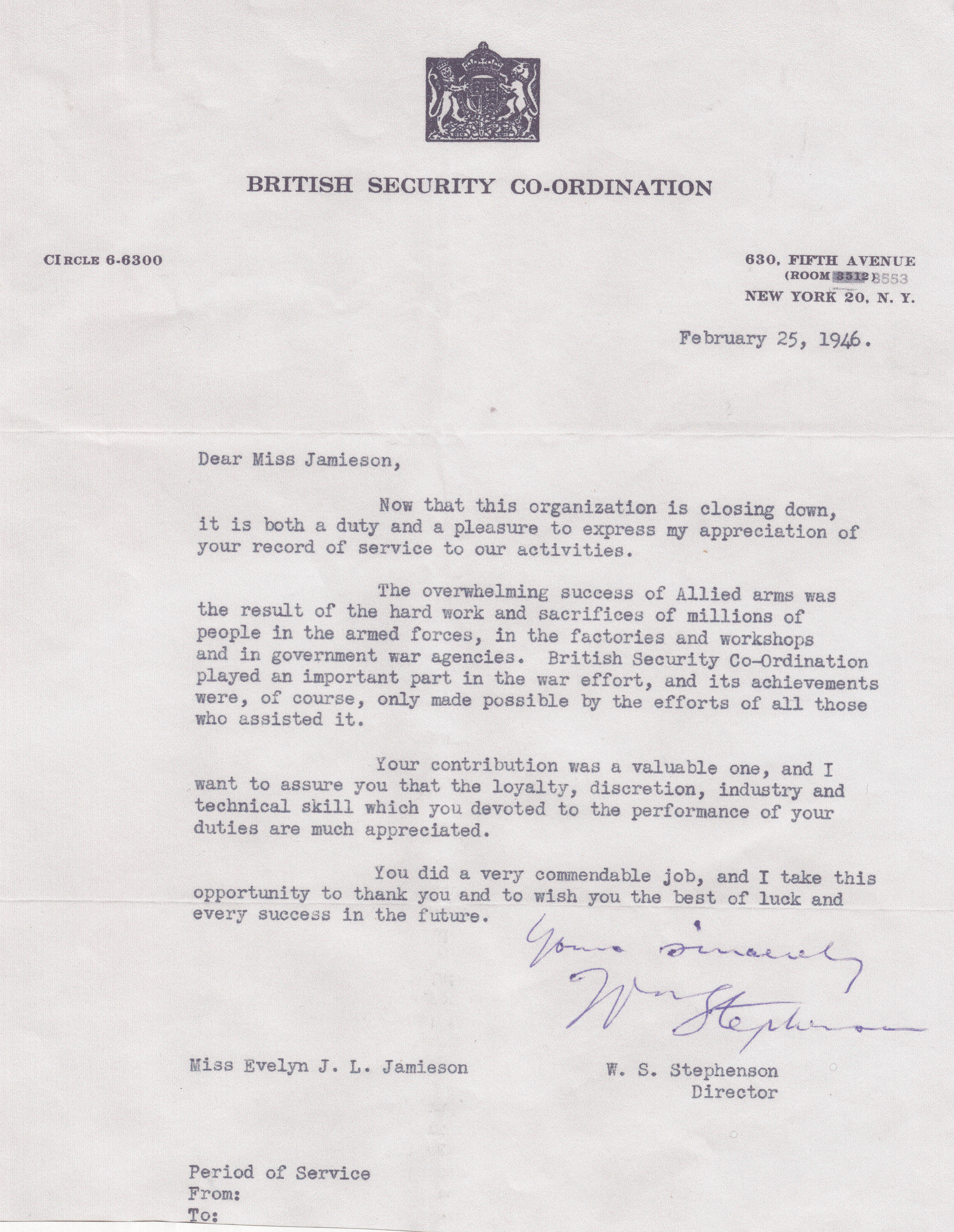

The origins of Camp X lay in the British drive to maximize support for the war effort from the United States, which was neutral at the time. William “Wild Bill” Donovan, appointed in July 1941 as US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Co-ordinator of Information, was keen to develop a cadre of secret agents, and Camp X was designed to help. William Stephenson (now widely known as Intrepid — although this was never in fact his code name, merely a telegraphic address he used after the war) was the principal facilitator of the project.

Stephenson had arrived in New York in 1940 as station chief for Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) in the United States. He used his wide network of contacts across Canada to locate and purchase a suitable site. The camp opened in early December 1941 and over the next few months trained several of its staff in the arts of secret warfare. The almost simultaneous US entry into the Second World War following Pearl Harbor meant that Donovan could openly establish his own schools. Donovan initially depended on the resources available at Camp X, including its syllabus, which provided the basic template for training American agents (see also Intelligence and Espionage).

In many significant respects, Camp X was also a Canadian operation. It relied on close support from the local military authorities and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), operated with the knowledge and consent of the government in Ottawa, and its adjutant quartermaster and NCOs were all Canadian. Hydra was heavily dependent on Canadian staff and locally recruited wireless operators.

Evolution

As the size of the American contingent declined, Camp X added new groups of recruits. During 1942, many came from Central and South America, where personnel from mostly British-owned or operated factories and businesses were taught security and counter-sabotage techniques to protect their enterprises from possible Nazi-inspired subversion. Later, a significant percentage of these recruits were recent immigrants to Canada from Europe who had the necessary language skills to operate behind enemy lines, such as Yugoslavian Canadians, who were recruited with the help of the then banned Communist Party of Canada. Italian and Hungarian Canadians were also trained there and eventually served behind enemy lines. Twelve French Canadians from Camp X went on to more advanced training in SOE’s British schools; four of them subsequently operated in France.

Training at Camp X was preliminary only, helping to identify those judged suitable for advanced and finishing courses in British schools. Once Canada had been thoroughly trawled for recruits, the training school was closed in April 1944. Although no accurate figures exist, it has been estimated that some 500 students passed through the camp.

Hydra continued to operate on the site as the crucial and secure radio communications link for high-grade intelligence material passed between BSC, Ottawa , London and Washington. It processed an increasing amount of traffic from Britain’s code-breaking centre at Bletchley Park, as well as for the American war and navy departments. The Canadian government was more deeply involved in this aspect of Camp X than it ever was in the training school.

It was in March 1946 that Canada first entered what is now known as the “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing community of states (Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and the United States), which came to maturity during the Cold War.

Women at Camp X

Members of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) served at Camp X (see Women in the Military). Most CWACs, as they were called, were assigned jobs typically given to women at the time, such as cooking, laundry and clerical duties. But women also pioneered roles in the mechanized and technical fields. At Camp X, such technical duties included sending and receiving communications, as well as transcribing and decoding the encrypted messages that passed through Hydra.

“After arriving at Camp X, we had one week to learn Morse code and Murray code [which used punched tape ribbons to transmit messages] before pitching in to translate incoming and outgoing calls to and from Britain,” Winnifred Davidson, a CWAC assigned to Camp X, told Legion magazine. “We used a Kleinschmidt teletype machine and messages came in via high-speed Morse code and went out on punch tape.

Evelyn Davis spent much of her time at Camp X working on the Boehme tape puller or undulator. “We were sending and receiving traffic to England and to New York and Washington,” Davis told The Memory Project. “It was many years after the war, we learned we were sending to Bletchley Park. All traffic was in five letter groups and plain English was never used. My knowledge of Morse code was important.

“We worked 365 days a year, 24 hours a day and there were several shifts, 8 to 4, 4 to 12, 12 to 8 and a couple of swing shifts.”

Civilian women also worked alongside enlisted CWACs at Camp X.

(See also Canadian Women and War.)

Cold War

Camp X provides another link to the Cold War. It was here that the Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko was hidden with his wife and child following his defection in Ottawa in September 1945. His revelations about the nature and extent of Soviet espionage against its wartime allies made the public more aware of Cold War spying. It was in the safety of the camp, protected by the RCMP, that he continued to speak freely about what he knew (Gouzenko had been speaking with the RCMP while sequestered in Ottawa and prior to his arrival at Camp X). It was at this time that a team of authors recruited by William Stephenson, including Roald Dahl, wrote the official history of the BSC.

Taken over by the Canadian government in 1947, Camp X operated as a military signals station until it was closed in 1969 and eventually demolished. A plaque now marks the site.

Legend and Legacy

Camp X has been subject to much mythologizing and highly inaccurate claims. Some assert that the assassination of top SS leader Reinhard Heydrich in Prague in 1942 as well as the operation to sabotage the Norsk heavy-water plant in Norway were planned and executed from Camp X. Others have argued that Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond series, was trained there.

The Camp X experience did have effects on postwar images of espionage. One of the STS 103 instructors was the writer Paul Dehn, who went on to write the screenplay for such notable films as Orders to Kill, Goldfinger and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Undoubtedly, too, Fleming’s friendship with Sir William Stephenson after the war helped fuel his imagination and inspire his fiction (some have said that Stephenson was the basis for Bond).

The site of Camp X is now called Intrepid Park, after Stephenson’s telegraphic address. The park holds two historic plaques, one dedicated to Camp X and the other to Stephenson.

Artifacts are often found at the site, including a round of smoke mortar ammunition unearthed in 2016. In 2010, a privately owned collection of Camp X artifacts and memorabilia was auctioned off. Later that same year, 15 items, including commando coveralls, a British suitcase radio and a piece of railway track used for demolition training, were purchased by the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

The CBC drama series X Company (2015) helped boost the camp’s legend as a major centre of behind-the-lines operations in occupied Europe.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom