Since its founding in 1918, the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) has been creating programs, providing services and advocating on behalf of Canadians who are blind or partially sighted (see Blindness and Visual Impairment). The non-profit organization was founded and incorporated by a group of seven Canadian men — including several military veterans — in response to rising blindness rates caused by the Halifax Explosion and the number of wounded veterans returning home from the First World War.

Before CNIB

Edgar Robinson had a vision to help Canada’s population impacted by blindness. Born in Stouffville (see Whitchurch-Stouffville), Ontario, in 1872, Robinson graduated from the Ontario Institution for the Education of the Blind in 1890. He would continue his education and become the first person with sight loss to graduate from a university in Canada (Trinity College BA in 1893 and an MA in 1903). He authored a book, The True Sphere of the Blind (1896), that discussed the state of education for people who were blind in Canada. Robinson was concerned that most libraries for people who were blind were geared to young students, and he wanted more adult readers to have access to embossed (raised print) books. In 1906, Robinson founded the Canadian Free Library for the Blind in his father’s home in Markham, Ontario.

Following Robinson’s death on 7 November 1908, the library relocated to Annette Street in Toronto in 1911. The library soon began supplying Canadians who were blind with various materials including music, embossed books, cards to play games, and Braille paper. The consequences of the First World War, however, would jumpstart a larger mission.

First World War

During the First World War, many Canadian soldiers overseas suffered eye injuries that were caused by a variety of factors, including bombs, the explosions from shells, and poisoning from mustard gas. Many received state-of-the-art rehabilitation at St. Dunstan’s Hostel for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors in England. But those who returned to Canada generally did not receive adequate care. Not only was training in Braille and the trades limited, but schools for students with sight loss in Canada were geared to a younger generation.

The Halifax Explosion

On 6 December 1917, a French ammunition ship struck another vessel and exploded in Halifax harbour (see Halifax Explosion; The Halifax Explosion and the CNIB). Along with many deaths, 5,923 people had eye injuries and hundreds of people suffered vision loss from the accident. Shattered glass blinded 41 people. Again, the options to rehabilitate people who were impacted by blindness were insufficient.

A National Organization Is Established

By 1917, the Canadian Free Library for the Blind, renamed the Canadian National Library for the Blind (CNLB), was a place where Canadians with sight loss received instruction in many areas including embossed print and typewriting, and employment services. But, as a small operation, the library was not large enough to care for people who were blind across Canada. In addition, antiquated belief systems that blindness was synonymous with a person’s weak physical and mental capacities were prevalent at the time. Therefore, unemployment and poverty were high for people who were blind. It was in this climate that seven board members of the library came together with a joint vision to expand the library’s mission.

Among the board members was Edwin A. Baker, who lost his sight on the battlefield during the First World War and went on to serve as managing director of CNIB from 1920 to 1962. Another was Sherman Swift, an accomplished poet who lost his sight as a child due to a gunpowder accident.

In March 1918, several months before the Armistice agreement was signed (see also Remembrance Day in Canada), the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) was established. The goal of the non-profit organization was “to serve the blind people of Canada and to prevent blindness.” (See also Blindness and Visual Impairment.) Soon, CNIB moved to a leased property at 186 Beverley Street in Toronto that had living and training quarters.

Early Work of CNIB

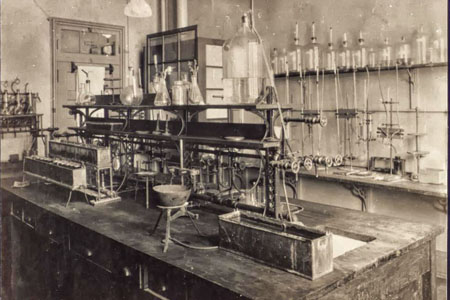

That same year, the Canadian National Library for the Blind (CNLB) was amalgamated with CNIB. Returning soldiers came to the library to receive training in many different subjects including Braille reading and writing, basketry and massage. By 1920, CNIB had established divisions in Ontario, Atlantic Canada and parts of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba (see Atlantic Provinces). Around this time, CNIB worked to locate and offer services to people who were blind in remote regions of central and northern Canada. In the 1920s, CNIB developed a job placement service that was among the first of its kind on the continent. CNIB also created employment opportunities that included broom making, piano tuning, basket weaving and news vending.

CNIB advocated for compensation for employees who experienced sight loss due to injuries or industrial diseases. This was achieved in Ontario when the Blind Workmen's Compensation Act was passed in 1931. (See also Workers’ Compensation; Occupational Diseases.) In 1937, after many years of advocacy by CNIB, the Old Age Pensions Act (see also Old-Age Pension) was changed, allowing provisions for people who were blind at the age of 40. In 1939, CNIB appointed a research committee to consider the needs of musicians and piano tuners with sight loss in Canada. The committee's findings resulted in the creation of a separate CNIB music department.

The 1950s and Beyond

In 1955, CNIB, the Canadian Ophthalmological Society (COS), and the University of Toronto created an eye bank in Canada in response to corneal blindness that was caused by chemical warfare during the Second World War. Since then, eye banks have been established across Canada that store human eye tissue for corneal transplants. (See also Ophthalmology.)

In 1956, a new national head office for CNIB opened at 1929 Bayview Avenue in Toronto.

In 1961, CNIB initiated the Wise Owl Club of Canada, a prevention program that aimed to promote workplace safety. In the 1970s, mobile eye care units (CNIB Eye Vans) were built to provide eye health care evaluations in Ontario, Newfoundland and eventually Quebec. This was also a time of technological innovation at CNIB, and talking books on cassettes were unveiled by the CNIB Library in the 1970s. In 1993, CNIB’s 75th anniversary was celebrated with the launch of the Technibus, which travelled across Canada allowing people who were blind or partially sighted to learn about the latest technologies.

In Recent Years

In 2014, CNIB helped to establish the Centre for Equitable Library Access (CELA) in partnership with public libraries. CELA provides books and other materials to Canadians with print disabilities (learning, physical or visual disabilities that prevent a person from reading print material) in the formats of their choice. In 2015, CNIB joined together with leaders in visual health to announce the Canadian Patient Charter for Vision Care, a pledge to improve the patient experience. In April 2017, CNIB launched CNIB Guide Dogs, a program designed to raise and train guide dogs exclusively for people with sight loss. (See also Dogs in Canada.)

CNIB Today

CNIB is a non-profit organization with the mandate “to change what it is to be blind through innovative programs and powerful advocacy that enable Canadians impacted by blindness to live the lives they choose.” A national network of volunteers, donors and partners help support the organization’s programs and services.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom