The Denesuline (also known as Chipewyan) are Indigenous Peoples in the Subarctic region of Canada, with communities in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Northwest Territories. The Denesuline are Dene, and share many cultural and linguistic similarities with neighbouring Dene communities. The 2021 census reported that 4,815 people claimed to be of Denesuline ancestry. However, the registered population of Denesuline First Nations may be higher. Denesuline are closely associated with other Dene groups as well as northern Cree and Métis, who may share their communities and also speak Denesuline. As such, population and language numbers are approximations.

Language, Population and Geography

The word “Dene” means “people” and serves many purposes. It is a collective term for people previously known as Athapaskans, and is often used as an equivalent to the Athapaskan language group. Dene may refer to the collective group (including Denesuline, Tlicho, Slavey, Yellowknives and others) as well as the specific Denesuline language. There are two dialects of Denesuline — the “k” dialect is far less common than the “t” dialect — and many communities are attempting to revive the language through youth education programs.

Linguistically, the Denesuline are closely related to the Tlicho, Slavey and Yellowknives, neighbouring Dene who speak similar languages and whose territories share borders. Traditional Denesuline territory includes northern portions of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the southern part of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. With the exception of Nunavut, contemporary Denesuline communities exist in the same areas, generally between Lake Athabasca and Great Slave Lake.

In the 2021 census, 4,815 people claimed to be of Denesuline ancestry. However, the registered population of Denesuline First Nations may be higher. There are Denesuline First Nations in Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories.

Traditional Life and European Contact

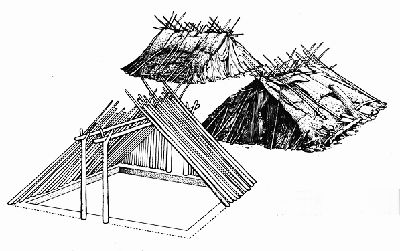

Traditional Denesuline socio-territorial organization was based on hunting the migratory herds of barren-ground caribou. Hunting groups consisted of two or more related families that joined with other such groups to form larger local and regional bands, coalescing or dispersing with the herds. Leaders had limited, non-coercive authority which was based upon their ability, wisdom and generosity. Spiritual power was received in dream visions and exercised by shamans, and reflected a worldview intertwined with the natural world. Catholic missionaries were successful in converting the majority of Dene in the area, superseding traditional belief systems.

In Denesuline tradition, it was Thanadelthur, also known as the "Slave Woman," who guided an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) into Denesuline territory and introduced her people to Europeans. This successful meeting led the HBC in 1717 to establish Prince of Wales Fort, or Churchill, for the Denesuline fur trade. The competition of the fur trade aggravated relations between Denesuline and their southern neighbours, the Cree. Until the late 18th century, the fur trade aggravated hostilities between the Denesuline and Cree as well as between the Denesuline and Inuit to the north. The Denesuline called the Inuit hotel ena or "enemies of the flat area."

The Yellowknives took advantage of their strategic location and in the early 19th century, briefly occupied the Yellowknife River region, displacing its Tlicho inhabitants until they retaliated in 1823. Some Denesuline began to hunt and trap in the full boreal forest, where fur-bearing animals were more abundant, and they extended their territories to the south. Some even began to occupy the northern edge of the parkland, where they hunted bison. Others remained more independent from the trade, though some were willing to trade food provisions. By the late 19th century most contemporary Denesuline communities had settled in their current territories. Epidemics of European diseases decimated the population, with the first great smallpox epidemic occurring in 1781–82, and other epidemics continuing through the first half of the 20th century.

Colonial Challenges and Contemporary Life

The Denesuline established formal relations with the Canadian government through the treaty process beginning in 1876. They experienced a century of federal policies intended to destroy their culture through assimilation—especially through residential schools. Denesuline ways of life were threatened especially in the 20th century, when they faced an increasing number of competing land uses, supported by federal and provincial government policies that encouraged the development of northern resource-based industries. As a result, it became increasingly difficult for Denesuline to support themselves by their traditional hunting and trapping economies, especially after the Second World War, when government policies encouraged Indigenous peoples to resettle in permanent administrative settlements, where most live today.

Contemporary Denesuline communities are regaining control over their communities and traditional lands by pursuing land claims and self-government agreements with the federal government. Denesuline are reviving traditional hunting and trapping, as well as seeking to protect their culture and language and to re-establish traditional relationships with the land.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom