Demasduit (also known as Demasduwit, Shendoreth, Waunathoake, and Mary March), creator of a Beothuk dictionary (born 1796; died 8 January 1820 at Bay of Exploits, Newfoundland). Demasduit was a Beothuk woman taken captive by English fishers in 1819. She was subsequently sent to an Anglican missionary where she created a list of Beothuk vocabulary. After her death, her remains and those of her husband were taken to Scotland. After much lobbying, the remains were returned to Newfoundland in 2020. The Government of Canada has recognized Demasduit as a Person of National Historic Significance.

Early Life and Capture

Demasduit was Beothuk, an Indigenous people who traditionally occupied what is now Newfoundland. In March 1819, she was captured by Europeans who were on an expedition in Red Indian Lake. Demasduit’s niece Shawnadithit witnessed the event and later drew a map depicting where her aunt’s capture took place. When Demasduit’s husband and Beothuk chief, Nonosabasut (Nonosbawsut), came to rescue her, he was killed by settlers. Demasduit’s and Nonosabasut’s newborn baby died shortly after the tragic altercation took place.

Preservation of Beothuk Language

Demasduit was taken to Twillingate and put in the care of Anglican missionary John Leigh. With her help, Leigh recorded on paper a Beothuk vocabulary. It consisted of 180 words.

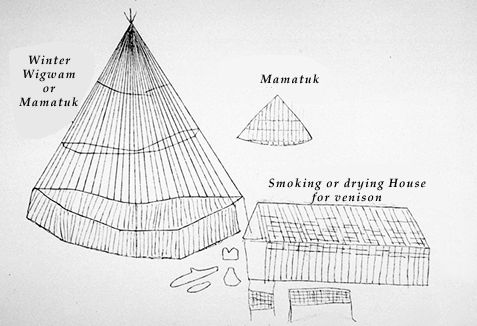

Two other Beothuk women were instrumental in the preservation of the Beothuk language. Oubee, a girl who was taken by the English from her home near Charles Brook in 1791, recorded the translation of 111 Beothuk words. Shawnadithit, who was brought to Scottish naturalist and merchant William Cormack in 1828, also recorded a Beothuk word list. Additionally, she drew maps of Beothuk territory and sketches of Beothuk material culture. (See also Indigenous Languages in Canada and Indigenous Territory.)

Death

Sometime after her capture in 1819, Demasduit was brought to St John’s. Europeans unsuccessfully attempted to return her to her own people. She was unable to locate surviving family.

Demasduit likely died of tuberculosis. Her body was returned to Red Indian Lake in February 1820 by a party led by British naval officer David Buchan.

Did You Know?

While it has been said that the Beothuk are now extinct, Mi’kmaq oral tradition denies this claim. Indigenous oral histories teach that the Beothuk intermarried with other Indigenous nations along the mainland after they had been forced out of their coastal territories by settlers. According to this perspective, Beothuk descendants live on in other Indigenous communities.

Repatriation of Remains

In 1827, William Cormack saw Demasduit’s body, placed side by side with that of Nonosabasut, in an elevated sepulchre erected by the Beothuk. Cormack took their skulls and sent them to Edinburgh, Scotland, where they were eventually housed at the National Museum of Scotland.

In 2015, Chief Mi’sel Joe of the Miawpukek First Nation at Conne River began a process to repatriate the remains. Joe travelled to Scotland to view the remains and performed a sweetgrass ceremony for the Beothuk people, a spiritual purification ritual meant to wash away negative thoughts and feelings. In February 2016, Newfoundland and Labrador premier Dwight Ball officially wrote National Museums Scotland to ask them to return the Beothuk remains to Canada. This was followed by a similar request in November 2017 from the federal minister of Canadian Heritage, Mélanie Joly. In January 2019, Gordon Rintoul, director of National Museums Scotland, announced that an agreement was reached with Canadian authorities to have the remains returned to Canada. After much lobbying, the remains were returned to Newfoundland in 2020.

Chief Mi’sel Joe believes that the repatriation of Demasduit and Nonosabasut’s remains could help to lessen Newfoundland’s “dark history.” In the past, Newfoundland’s school curricula erroneously blamed the extinction of the Beothuk on the Mi’kmaq. It accused the Mi’kmaq of killing off the Beothuk at the request of the French. The repatriation, Chief Mi’sel Joe believes, could lead to a chapter of reconciliation for the Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Legacy

Demasduit’s written record of the Beothuk language has helped to preserve her people’s culture. In 2007, she was recognized by the Canadian government as a person of national historic significance.

The Mary March Provincial Museum in Grand Falls-Windsor, Newfoundland, was named for her, using an English version of her name. In 2022, the museum changed its name to the Demasduit Regional Museum. This was done out of respect for Demasduit and the Beothuk, and as a step toward reconciliation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom