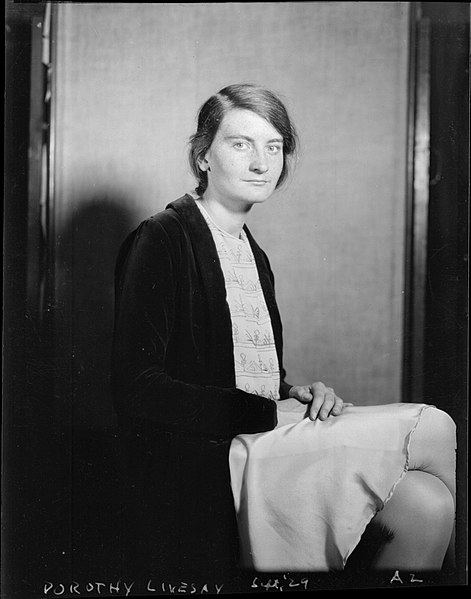

Dorothy Kathleen May Livesay, poet, journalist, educator, activist (born 12 October 1909 in Winnipeg, MB; died 29 December 1996 in Victoria, BC). Dorothy Livesay was one of Canada’s most influential modernist poets. She was a communist activist in the 1930s and had careers as a social worker, teacher and university instructor, journalist, literary critic and editor. She was also an advocate for social justice and equal rights.

Childhood and Education

Dorothy Livesay was the older of two daughters of journalists Florence Randal Livesay and J.F.B. (John Frederick Bligh) Livesay. Her sister, Sophie, was three years younger. Both parents fostered Livesay’s literacy from an early age. Her mother, who had written poetry herself and ran a column in the Winnipeg Free Press, published the child’s playful questions and stories before Dorothy could write, and her father, an advocate for women artists, provided her with books (many written by women) and later supported her career.

In 1921, the family moved to the Toronto area, where J.F.B. Livesay became the general manager of the Canadian Press. Dorothy Livesay attended Glen Mawr School, a private girls’ school with a focus on the arts. She was a good student, interested in music, theatre and literature. She also began to write poetry while at Glen Mawr. Her first poem was published when she was in her early teens, submitted to a newspaper by her mother without Livesay’s knowledge. She also won a school prize for a short story.

During high school, Livesay formed a close friendship with Jean Watts (who prominently features in her memoirs as Gina or Jim); Watts was the only person to read most of her early poetry. The two young women became interested in feminist ideas after attending a series of lectures by Russian anarchist Emma Goldman.

University Years and Early Publications

In 1927, Dorothy Livesay entered Trinity College at the University of Toronto to study French and Italian. One year later, when she was 18, her first volume of poetry was published under the title Green Pitcher. According to Livesay, her mother’s initiative was the driving force behind this publication. But Livesay also began to submit her own writing. In January 1929, she had a short story, Heat, published in the modernist literary magazine Canadian Mercury; around the same time, her poem “City Wife” won U of T’s Jardine Memorial Prize for English Verse. She also began acting in, as well as directing, student theatre productions.

In her third year (1929–30), Livesay spent eight months in Aix-en-Provence, France, for intensive language studies. During that time she wrote short stories as well as a novella, Pavane, which remains unpublished. Back in Toronto for her final year, Livesay became part of a circle around Otto van der Sprenkel, a young Dutch economics professor who hosted seminars about communism. After graduating with her B.A., she went to Paris for a year (1931–32) to obtain a Diplôme d’études supérieures from the Sorbonne. Her second book of poems, Signpost, was published after her return in 1932.

Communist Activism

In Paris, Dorothy Livesay’s interest in communism deepened, as it did among her circle of foreign students. (Notably, Stanley Ryerson was her live-in boyfriend for part of the year; he features as Tony in her memoir, Journey with My Selves). Livesay witnessed police brutality at a workers’ rally, attended communist meetings and read Marx and Engels. In September 1931, she wrote to a friend: “Certainly Europe’s in one hell of a mess. I don’t see any way out but the death and burial of Capitalism.” And in July 1932: “I want to think and belong to, work for, the proletariat (...).” She distanced herself from the lyrical poetry of her first two books, now believing that poetry should concern itself with social struggles and everyday life. This viewpoint inspired both the argument in her thesis for the Sorbonne, a critical examination of T.S. Eliot, and the poetry she published in Canadian communist culture magazines over the following years.

Upon her return to Toronto in the summer of 1932, Livesay was eager to transform communist theory into activist practice. “My political convictions became the dominating obsession of my life,” she writes in her memoir, Right Hand Left Hand. She enrolled in U of T’s School of Social Work (now Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work) for a two-year diploma. At the same time, she became involved with communist groups on campus such as the Young Communist League and the Progressive Arts Club (PAC) and eventually became a Communist Party (CPC) member in 1934.

For the second year of her social work programme (1933–34), Livesay completed her fieldwork requirement with the Family Service Bureau in Montreal. There she experienced poverty among working-class families first-hand, deepening her commitment to activism. She joined a local communist group, participated in rallies, hosted meetings and wrote leaflets, chants and propaganda plays. After graduation she became a case worker in Englewood, New Jersey, with a recreation agency serving the Black population of the town; this was her first exposure to racial segregation. (See also Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada.)

Mental health issues forced Livesay to return to Canada in the fall of 1935 and live with her parents. She reunited with Toronto comrades and focused on writing again, developing her poetry beyond proletarian propaganda into a more holistically humanist voice. This shift was guided by her own experiences and also, probably, by a change in the CPC’s cultural dogma toward accepting “bourgeois” influences.

Moving West and Marriage

In the spring of 1936, Dorothy Livesay went on a reading tour of the western provinces. She had just become an editor with the new communist literary journal New Frontier, launched by her friend Jean Watts and Watts’s husband William Lawson; it was decided Livesay would stay in Vancouver as the journal’s western editor. One of the contacts she made there in her efforts to promote readership was Duncan Macnair, an accountant and fellow socialist from Scotland. She married him in August 1937.

Livesay had found employment with the BC Welfare Field Service but had to quit her job after getting married. At the time, employment was seen as incompatible with the duties of a wife and mother. Many employers, including federal and provincial service providers, forced women who married to resign. This caused an episode of depression, but Livesay eventually turned to volunteer work. She connected with local creatives and activists to build a community centre, where she organized a writing group.

Livesay’s children Peter and Marcia were born in 1940 and 1942, respectively. Out of financial necessity, she continued to write: poetry, newspaper articles, radio scripts for the CBC. Meanwhile, her marriage suffered from conflict, including an incident of domestic abuse.

National Successes

In 1941, Dorothy Livesay and Victoria poets Anne Marriott, Floris McLaren and Doris Ferne founded Contemporary Verse, one of the first literary magazines in the west, with Alan Crawley as editor. It became an important medium both for established and young poets, especially women, until it ceased publication in 1952. In 1944, Livesay published her poems from the late 1930s in the collection Day and Night, which won the Governor General’s Literary Award. The subsequent publication Poems for People won the same award in 1947. That year, she also received the Lorne Pierce Medal from the Royal Society of Canada for distinguished contribution to Canadian literature.

While no longer an active communist, Livesay remained invested in world events and social justice. Her writing reflected these concerns. Topics include the struggle against fascism in the Spanish Civil War (Catalonia, 1939) and the suffering of Japanese Canadians held in internment camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor (Call My People Home, a documentary poem aired on the CBC in 1949 and published in 1950). She also worked as a postwar correspondent, spending several months in England and Germany in the fall of 1946 to report for the Toronto Star.

Teaching Career

In the early 1950s, Dorothy Livesay was hired by the University of British Columbia as a creative writing instructor. Later, with her children in school, she decided to make teaching a livelihood and obtained a teaching certificate from UBC in 1956. She taught at a Vancouver high school for two years before successfully applying for a grant to study teaching English at the University of London, England. While there, in February 1959, she received the news that her husband had died. According to her memoir, Journey with My Selves, her first thought was I’m free.

Later that year, Livesay went to Paris to work with UNESCO. She accepted a field appointment to Northern Rhodesia (which achieved independence from the British crown as the Republic of Zambia in 1964) and taught English at teachers’ colleges in Kitwe and Lusaka from 1960 until 1963. Back in Vancouver, she returned to UBC to receive a M.Ed. in 1966. From then until 1984, she served as instructor and writer-in-residence at various Canadian universities, including the University of New Brunswick, University of Alberta, University of Manitoba, University of Toronto and several universities in British Columbia.

Later Work and Recognition

After her return from Africa, Dorothy Livesay embarked on a new phase of her writing career. The poetry in The Unquiet Bed (1967) draws on her experiences in Zambia, and Plainsongs (1969) deals openly with female sensuality and sexuality. Her later poetry, starting with Ice Age (1975), expands to themes of a female community, of old age and death, and thus the entirety of women’s lives.

In 1975, Livesay founded the poetry magazine CV/II, successor of Contemporary Verse. She was also affiliated with other literary publications, contributing significantly to literary criticism in Canada and to the definition of a specifically Canadian poetry. Furthermore, she was active in the League of Canadian Poets, Amnesty International and other literary and humanist organizations. In 1977, Livesay received the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Medal, followed by the Governor General’s Award in Commemoration of the Persons Case for outstanding contributions to gender equality in 1984. She was named an officer of the Order of Canada in 1987 and inducted into the Order of British Columbia in 1992. She also received many honorary doctorates from Canadian universities, including UBC, the University of Waterloo, the University of Toronto and others.

Livesay settled on Galiano Island, British Columbia, during the last few years of her life. She died there on 29 December 1996, at the age of 87.

Legacy

Dorothy Livesay is widely regarded as one of Canada’s best and most influential modern poets, as well as a leading voice for justice, peace and women’s rights. Her work — poetry and prose, much of it autobiographical — spans six decades and touches on many social and political events of the 20th century. From an early imagist style under the influence of Amy Lowell, Emily Dickinson or Ezra Pound and the polemic, social-realism-influenced poetry of her active communist years, her writing evolved into a candid, powerful voice exploring the many facets of womanhood.

Livesay’s writing is the subject of a large body of scholarly work. Some of her poetry has been set to music by Canadian composers, including Violet Archer and Barbara Pentland. The BC Book Prize for poetry, established in 1986, was renamed Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize in 1989 in her honour.

Throughout her life, Livesay balanced traditional ideas of marriage and motherhood with independence and self-expression, from practicing birth control as a young woman to reading her sexually explicit poetry in seniors’ residences in her eighties. A 2017 Vancouver Sun article calls her “a symbol to the feminist movement despite her refusal to wear the term feminist.”

Honours and Awards

- Governor General’s Literary Award (Day and Night, 1944; Poems for People, 1947)

- Lorne Pierce Medal, Royal Society of Canada (1947)

- Queen’s Silver Jubilee Canada Medal (1977)

- Governor General’s Award in Commemoration of the Persons Case (1984)

- Officer, Order of Canada (1987)

- Member, Order of British Columbia (1992)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom