Canada’s current and future prosperity depends on recruiting immigrants. Newcomers fill gaps in the Canadian workforce, build or start businesses and invest in the Canadian economy. Economic immigrants include employees as well as employers. They mostly become permanent residents when they immigrate to Canada. Not included in this class are the many temporary foreign workers who contribute to Canada’s economy. (See also Immigration to Canada.)

Economic immigrants bring talent, innovation, family members and financial investments to Canada. They also enrich the country’s culture, heritage and opportunities. Technological progress, productivity and economic growth all benefit from these newcomers. Studies show that they have little to no negative impacts on wages for other workers in the country.

According to the 2021 census, 1.3 million immigrants settled in Canada between 2016 and 2021. The census identifies 748, 120 of the total 1.3 million living in Canada economic immigrants.

Overview

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act of 2001 lays out Parliament’s goals for Canada’s immigration policy. Broadly, immigration policy aims to “support the development of a strong and prosperous Canadian economy.” In this vision, “the benefits of immigration are shared across all regions of Canada.” The federal government oversees immigration policy, primarily through Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). This ministry sets targets for numbers of newcomers and revisits these targets every fall. IRCC consults with industry, the provinces and territories, settlement service providers and other partners. (See also Quebec Immigration Policy.)

Economic immigration helps ensure that Canada’s population and labour forces continue to grow. Canada has an aging population and low fertility rates (i.e., the number of children born per woman). According to the 2021 census, approximately one in four Canadians were identified as foreign-born, the highest rate among the G7 countries (see Canada and the G7 (Group of Seven)). From 2016 to 2021, Canada’s population grew by 5.4 per cent and immigrants made up about 71.1 per cent of that growth. By the year 2040, immigrants will likely drive all of Canada’s population growth. Economic immigrants are generally younger than the Canadian-born population. Because of this, economic immigration lessens the aging of Canada’s labour force. In 1971, Canada had 6.6 people of working age for each senior citizen. By 2012, the worker-to-retiree ratio dropped to 4.2 to 1. Projections put the ratio at 2 to 1 by 2036, when five million Canadians are set to retire.

In a global market, Canada is competing to attract talent. Other industrialized countries, like the United States, seek skilled immigrants. So do emerging markets like Brazil and India. In 2005, 22 per cent of countries had policies aimed at quickly resettling highly skilled immigrants. By 2015, this proportion had doubled to 44 per cent.

How Does Canada Select Immigrants?

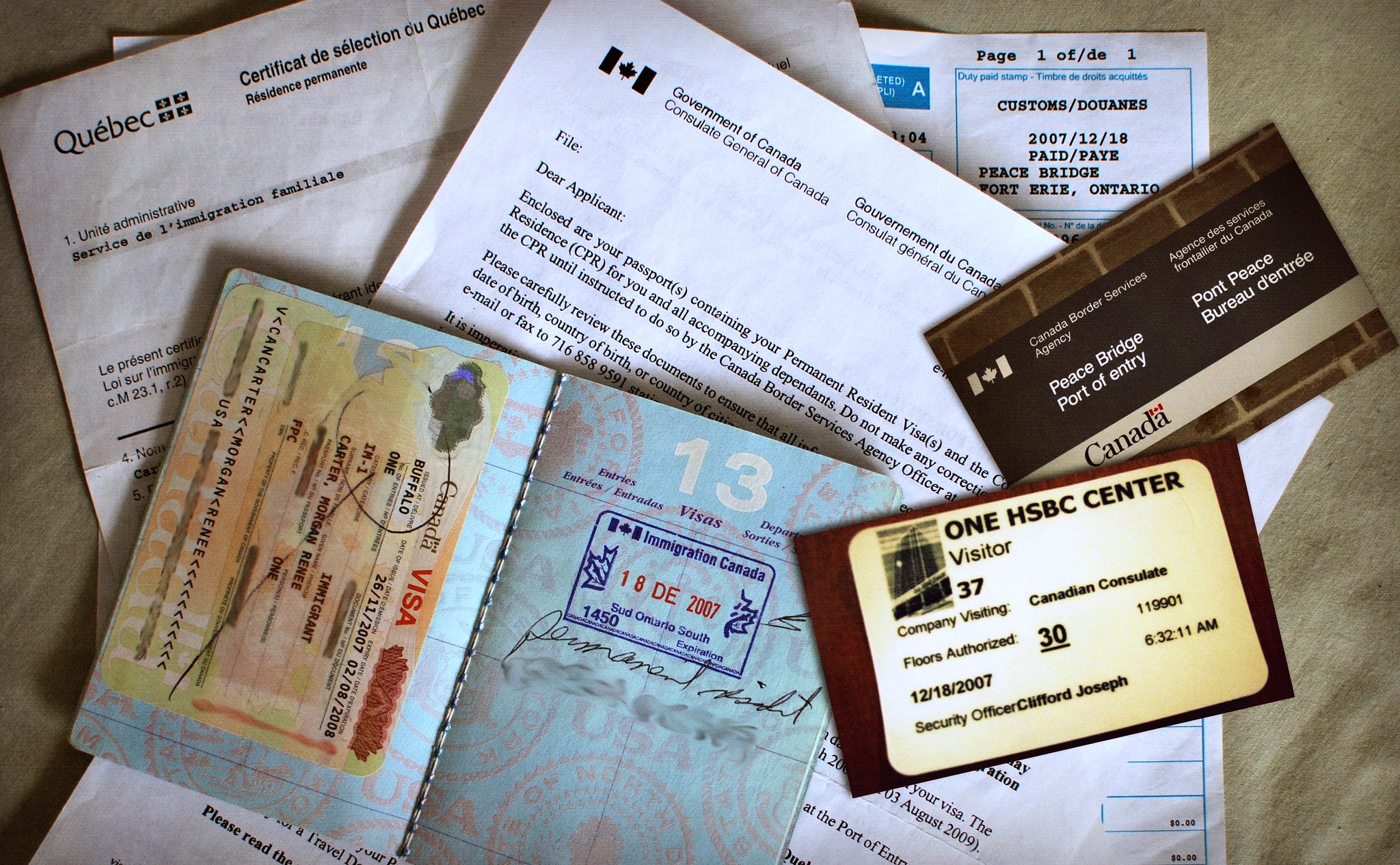

Economic immigration is one of several immigration categories. As a pathway to residence in Canada, it is distinct from family reunification and refugee and humanitarian protection status. Before moving to Canada and taking a job, immigrants must apply for a permanent residence visa from IRCC. Canada has a points-based system for selecting labour immigrants. This system prioritizes human capital, Canadian education and job offers.

The Canadian government introduced the first points-based system in 1967. (See Immigration to Canada). It updated this system in 1993 after a massive backlog of applications led to wait times of more than five years.

The government implemented the electronic Express Entry system in 2015. Express Entry fast-tracks skilled immigrants with Canadian work experience or pre-arranged employment. It draws more and more on temporary workers and international students already in the country (see Canada's Temporary Foreign Worker Programs). Express Entry provides three major pathways for highly skilled workers to immigrate to Canada. (Examples of highly skilled workers are doctors, computer programmers and architects.)

|

Pathway |

Who it’s for |

|

Federal Skilled Worker Program |

Skilled workers with foreign work experience who want to immigrate to Canada permanently. |

|

Federal Skilled Trades Program |

Skilled workers who want to become permanent residents. |

|

Canadian Experience Class |

Skilled workers who have Canadian work experience and want to become permanent residents. |

Would-be immigrants fill out applications to enter a pool of candidates wishing to move to Canada. Express Entry’s point system uses a matrix of several factors to rank these applications. It accounts for skills, work experience, language ability and education. The system may award points for other factors, such as having a sibling or a job offer in Canada. IRCC prioritizes these factors because they potentially enhance an immigrant’s ability to integrate quickly into Canadian society and to contribute to the economy. IRCC then issues a certain number of visas to those selected to move to Canada. This number depends on its pre-set yearly targets.

Opportunities and Challenges

Many see Express Entry as a more objective assessment than other countries’ migration management systems. This is because Express Entry draws on observable characteristics. It notably replaced the previous first-come, first-served system that had frustrated many people. The less predictable former system would speed admissions up or slow them down depending on the economy. Champions of the current Canadian point system say it is free of prejudice. They cite the fact that a person’s ethnic background or country of origin plays no part in the selection process.

Nevertheless, scholars note several challenges to equity and justice with Express Entry and the points-based system.

First, selection does not equal a job. Canada admits more highly skilled immigrants than it can quickly move into the workplace. One major cause of this gap is that Canada does not recognize many credentials obtained abroad. This is notably true in medical, dental and veterinary fields. When faced with this problem, newcomers are unable to apply the skills and education for which they were chosen. They must either do other work or go back to school. Many therefore take “survival jobs” but do not reach personal or career fulfillment in Canada. Capacity in either of Canada’s official languages may pose a separate or additional barrier to using one’s skills in Canada. Sometimes immigrants may appear less skilled compared to the general population, but this gap closes over time as their English and/or French language acquisition improves.

Second, it takes time and money to immigrate. Processing times for applications are still quite long. The administrative fees are barriers for many people. These fees are also non-refundable with no guarantee of success.

Finally, under a policy known as medical inadmissibility, IRCC will reject some candidates due to their own or their children’s medical issues. This policy is roundly criticized as discriminatory and ableist.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom