Family reunification is an immigration category that allows families to reunite. A person established in Canada can apply to immigrate a close family member from abroad. Family unity is a principle recognized by universal law.

In 2022, 105 000 people were granted permanent residency in Canada through this program, representing 24.3% of the total number of immigrants (431 645).

History

The first references to a reunification of families residing in Canada date back to the 19th century, and especially to the early 20th century.

According to the 1881 Naturalization and Aliens Act, if a man is naturalized as a "British subject of Canada", so are his wife and children.

After the Second World War, family reunification became an immigration category in its own right. This period laid the foundations of contemporary immigration, both economic and social. The 1952 Immigration Act facilitated family reunification, allowing members of the extended family to be welcomed. However, it favoured the admission of people from certain countries. The Minister and immigration officers were permitted, at their discretion, to refuse to admit people on the basis of their nationality or ethnic group (see Racism).

The selection of immigrants by race and nationality ended in the 1960s. A 1967 regulation created a points system based on established criteria such as education and professional skills. Thereafter, family reunification was gradually opened up to all. “Dependent" members of the immigrant's family were exempted from the points system, while other family members, known as "designated", were subject to it.

Following the 1976 Immigration Act, family reunification became more widely accepted and encouraged. Family immigration took on an increasingly important role in Canadian policies (see Immigration Policies in Canada). This trend was temporarily interrupted in 1995, in an effort to limit such immigration.

The 2001 Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and its 2002 regulations are still in place today. They give applicants the right to sponsor a spouse or common-law partner, including those of the same sex.

In December 2011, following a temporary freeze on new sponsorship applications, Stephen Harper's government introduced a super visa for parents and grandparents of permanent residents or citizens.

In January 2017, the federal government launched the lottery system for the Parents and Grandparents Program, a restricted program with higher financial requirements.

Family Reunification Policy in Canada

The right to family reunification is established by the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, particularly section 12, and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations.

Permanent residents and citizens, as well as refugees and protected persons, can apply to reunite with their families living abroad. Spouses, domestic partners and children are more frequently reunited than parents and grandparents. In 2021, spouses, common-law partners and children accounted for just over 85% of program admissions.

Canada’s immigration policies, including family reunification, are also designed to boost the country's economic development. A government report states that the majority of sponsored domestic partners and some parents and grandparents contribute to the family income. People who arrive through family reunification are granted permanent residency and can settle in the country and work freely. Bringing families together benefits the Canadian economy, as well as the well-being of immigrants themselves. This program enables them to maintain a healthy long-term settlement.

How does the program work?

Spouses, common-law partners, domestic partners, dependent children under 22 or in the process of adoption, parents and grandparents may be sponsored. Under certain conditions, applicants can also sponsor brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews, and orphaned grandchildren. However, citizens and permanent residents must declare themselves guarantors for the persons they sponsor.

The guarantor must sponsor their family member, provide for their basic needs and support them in the arrival and integration process. They must reimburse the government if it has to pay welfare benefits to the sponsored person during the period in which the guarantor is financially responsible for the sponsored person. (See also Welfare State.)

Since September 2019, as part of a pilot project, refugees have been able to sponsor their spouse, common-law partner or domestic partner, as well as their biological or adopted child under the age of 22, if this family member was not declared in the initial application.

The sponsored person has the right to receive integration services. They benefit from several rights such as social protection and, with a work permit, the right to work, etc.

If a reunification application is refused, it may be appealed to a division of the Immigration and Refugee Board.

Federal Jurisdiction

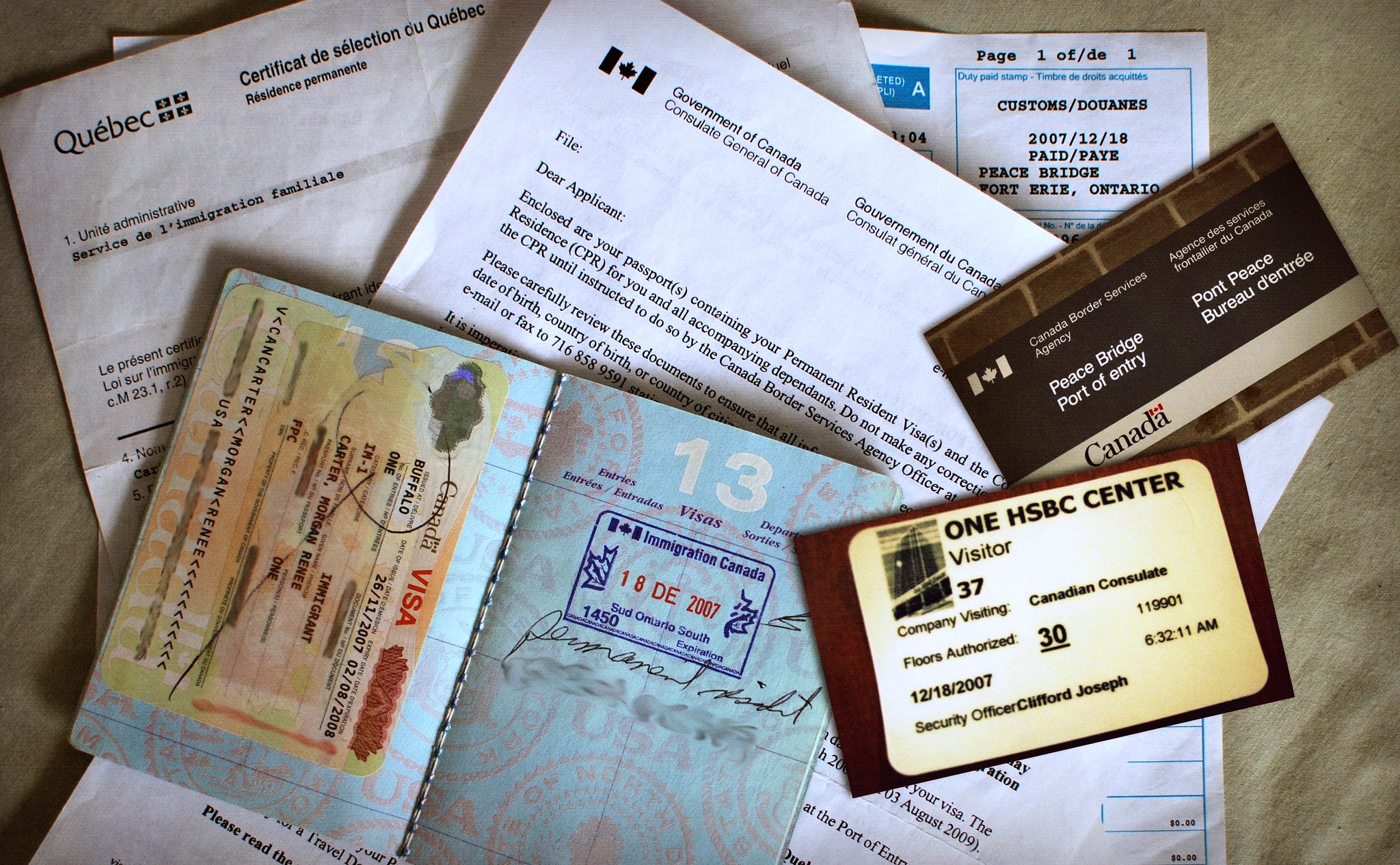

Family reunification is one of the three categories of immigration to Canada managed by the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship (IRCC).

Under the 1991 Canada-Quebec Accord, the federal government alone is responsible for family reunification and protected persons applications. However, for those living in Quebec, documents must be submitted to the Ministère de l'Immigration, de la Francisation et de l'Intégration. In Quebec guarantors are responsible for sponsored persons for a period of three years in the case of a spouse (see Quebec Immigration Policy.)

IRCC sets the program's annual targets in two categories. The first category is spouses, common-law partners and children, and the second category is parents and grandparents.

A Criticized System

Canada's family reunification system is criticized by civil society due to long processing times and loopholes that make it difficult for many families to reunite. Refugees are particularly affected by these issues.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated processing times for immigration applications in all categories. Those for family reunification, which can take more than two years, are widely contested.

For the parents and grandparents category, a random selection system was introduced in January 2017 before being replaced in 2019 by a "first come, first served" system. Tens of thousands of people reported not being able to complete their applications quickly enough. In 2019, 43,666 applications were in the inventory, but only 22,011 of them were approved.

In light of the criticism, Justin Trudeau's government reinstated the lottery in 2020 to make the system "fairer and more transparent". But many immigrants to Canada feel that the lottery is not fair, but rather unfair.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom