The movement of individuals of one country into another for the purpose of resettlement is central to Canadian history. The story of Canadian immigration is not one of orderly population growth; instead, it has been — and remains one — about economic development as well as Canadian attitudes and values. It has often been unashamedly economically self-serving and ethnically or racially discriminatory despite contributing to creating a multicultural society (see Immigration Policy in Canada; Refugees to Canada). Immigration has also contributed to dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their ancestral lands.

This article is a full-length entry about immigration to Canada. For a plain-language summary, please see Immigration to Canada (Plain-Language Summary).

Immigration to New France (16th–18th Century)

Throughout the 17th and much of the 18th century, European colonial administrations, charged with overseeing what would become Canada, did not consider settlement a priority. French or British governments initially seemed unprepared to expend vast quantities of money or energy necessary to encourage settlement. Nor was migration to Canada popular in France or Britain. Adventurers, explorers, and particularly traders acting for British or French interests feared the interference of settlers in the lucrative trade (see Fur Trade).

However, policy eventually changed and colonial authorities carefully and slowly encouraged settlement in Canada. It was their hope that settlers would guarantee the sovereignty of colonial land claims and exploit natural resources — often on behalf of European investors. It was also hoped that the settlers would convert Indigenous peoples to Christianity. Settlements grew gradually but not without difficulty. New France's population at the time of the British Conquest (1759–60) was about 65,000. In Nova Scotia, a transplanted Scottish community was supplemented by German and Swiss settlers. In the late 1700s, Irish settlers reinforced Newfoundland's population.

Although the British victory limited migration from France (see also French Immigration in Canada), it did not immediately bring about a large number of English-speaking immigrants. Except for a handful of British administrators, military personnel, and merchants who filled the vacuum left by their departing French counterparts, few English-speaking settlers seemed interested in Canada. Indeed, it is doubtful whether settlers would have been welcomed by the new British administrators. The latter feared that an influx of English-speaking Protestant settlers would complicate administration in a recently conquered Roman Catholic French-speaking territory. Most British migrants were far more inclined to seek out the more temperate climate and familiar social institutions of the American colonies south of Canada.

Loyalist Immigration (18th–19th Century)

Many of Quebec's new British rulers were soon forced to accept many thousands of English-speaking and largely Protestant settlers displaced by the American Revolution. Known as United Empire Loyalists, they were largely political refugees. Many of them migrated northward not by choice but because they had to. Many either did not wish to become citizens of the new American republic or because they feared retribution for their public support of the British. For these Loyalists, Canada was a land of second choice, as it would be for countless future immigrants who came because to remain at home was undesirable, and entry elsewhere, often the US, was restricted.

Loyalist migration was supported by Canadian authorities who offered supplies to the new settlers and organized the distribution of land. Despite the hardships the settlers endured, their plight was made less severe by the intervention of government agents, a practice to be repeated in Canada many times.

Many Black Loyalists also left the United States for British North America. Despite having sided with the British during the American War of Independence, Black Loyalists faced racist hostility and considerable inequality. Despite this, they persevered and built strong communities, particularly in towns like Shelburne and Birchtown in Nova Scotia. (See also The Arrival of Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia.)

Irish Immigration (19th Century)

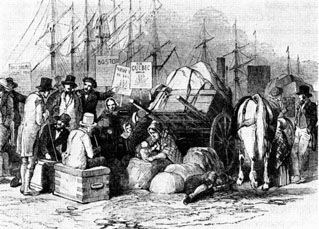

Throughout the mid-19th century, the colonies — Canada West in particular — returned to a pattern of painfully slow and erratic economic growth. Officially encouraged immigration from Britain and even the US gradually filled the better agricultural lands in the colony and bolstered new commercial or administrative towns. The new immigrants were generally similar to that of the established community. However, the great Irish potato famine and, to a lesser degree, a series of abortive European rebellions in 1848 sent new immigrant cohorts to North America.

Of these tens of thousands migrants, many were Irish whose arrival in Canada initiated major social and economic changes. In many respects, the Irish were Canada's first major cohort of overseas immigrants after the English and French. Although the Irish generally spoke English, they did not mirror the social, cultural or religious values of Anglo-Canadians. They formed a Roman Catholic minority in a predominantly Protestant Canada-West. Irish Catholics were, however, a bit more at home with French Canadians who shared their faith but not their language. Many of these Irish migrants’ loyalty to the British Crown also appeared suspect in a Canada where ardent loyalty was demanded as insurance against the threat of American republicanism.

After escaping an agrarian life where agriculture was synonymous with poverty and dependency, some of the famine-stricken Irish had little or no enthusiasm for farm life (see History of Agriculture). Instead, the Irish worked seasonally in the newly expanded canal system, lumber industry, and burgeoning railway network. Due to their less fortunate social-economic status as well as their distinct ethnic and religious identities, separate Irish neighbourhoods popped up in Canadian cities and larger towns.

Western Migration (19th–Early 20th Century)

With a relatively low death rate, high birthrate, and small but continual migration from the British Isles, the immediate post-Confederation era had its overpopulation problems ( see Population). This issue was further compounded by the increasing rarity of farmable land.

Meanwhile, the US — with its seemingly boundless supply of free, fertile land — attracted thousands of new immigrants and Anglo-Canadians. American industry attracted many French Canadians were to work in the factories of New England (see Franco-Americans).

Towards the late 19th century, Canada's future Prairie provinces were opened to settlement, but only after — sometimes violently — displacing First Nations and Métis peoples off their lands. (See also North-West Rebellion.) However, large scale migration only picked up when the need for agriculture products like wheat also increased.

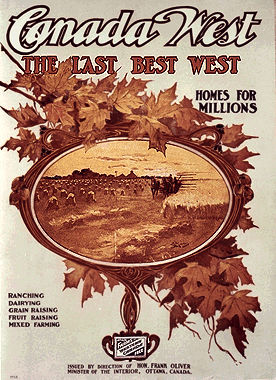

The demand for farm goods, especially hard wheat, coincided with the election of Wilfrid Laurier's government, which encouraged western settlement with large-scale immigration. Canada's new minister of the interior, Clifford Sifton, organized a revamped and far-reaching immigration program. He was even prepared, if not reluctantly, to admit agricultural settlers from places other than the British Isles, Northern Europe, and the US. Sifton’s willingness to open immigration outside of traditional sources was not, however, reflective of Canadian immigration policy.

For English-speaking Canadians, the traditional definition of ideal immigrants may have been modified but was not radically altered. The Canadian government preferred white English-speaking migrants from within the British Empire and from the US. At the same time, non-white migrants were denied entrance on racist grounds. The ideal immigrants were British or American independent farmers who would settle in the West.

Pressed by business and railway interests to increase immigration, immigration authorities balanced their ethnic anxieties against a frantic search for settlers. They listed ideal settlers in a descending preference. British and American agriculturalists were followed by French, Belgians, Dutch, Scandinavians, Swiss, Finns, Russians, Austro-Hungarians (see Austrians; Hungarians), Germans, Ukrainians, and Poles. Close to the bottom of the list came those who were, in both the public and the government's minds, less assimilable and less desirable, e.g., Italians, South Slavs, Greeks and Syrians (see Arab Canadians). At the very bottom came Jews, Asians, Roma people, and Black people.

Ottawa, however, did not have the only voice when it came to immigration. The British North America Act also gave the provinces a voice in immigration if they chose to do so. Quebec was particularly interested in doing so and set up its own immigration department. This was partly in response to the expansion of English-speaking Canada and in an effort to stem, if not reverse, the migration of rural Quebec youth to New England. In co-operation with federal authorities, immigration agents were sent into New England to encourage French Canadians to return home to settle new but marginal agricultural lands. The program was met with only limited success, but Quebec's involvement in managing its own immigration priorities continued.

Migrants and Urban Centres

In spite of government precautions, not all immigrants committed themselves to resource exploitation or agriculture. Like the Irish before them, many non-English speaking and largely non-Protestant immigrants rejected a life of rural isolation, choosing to work in cities. Furthermore, many of these migrants only saw themselves as living in Canada or North America temporarily. Some sought to earn enough money to buy a piece of land at home, to assemble a dowry for a sister, or to pay off a family debt. However, the many who adopted North American definitions of success or who were unable to return home because of political upheavals established themselves in Canada. If possible, they brought their wives and children to join them.

Migrants of increasingly diverse origins started migrating to Canada, these included Macedonians, Russians, Finns, and Chinese people. Many of these new migrants had been allowed into Canada to satisfy the need for cheap labour or a pool of skilled craftsmen for factory or construction work. Some worked in mining or lumbering, others like the Chinese worked to finish the Canadian Pacific Railway. Many settled in the major cities like Montreal, Winnipeg, Toronto, Hamilton, and Vancouver. However, these immigrants were confronted by ethnic and religious anxieties and prejudices previously only reserved for the Irish.

The arrival of migrants from drastically different cultural backgrounds generated some racist hostility from many Canadians. Some Canadians responded with a dignified tolerance. They recognized that these foreigners were here to stay, that their labour and skills were necessary, and that their living conditions were subject to improvement. Immigrants played vital economic role in urban centres — laying streetcar tracks, labouring in the expanding textile factories and digging the sewer systems. Yet, many Canadians nonetheless demanded a stricter control on immigration along ethnic or racial lines.

Immigration and Racism

Canadian immigration policy and administration had bowed to economic necessity by allowing some migrants into Canada. However, it only did so reluctantly. Soon enough, restrictive immigration controls were put in place to stop immigration along ethnic and racial lines.

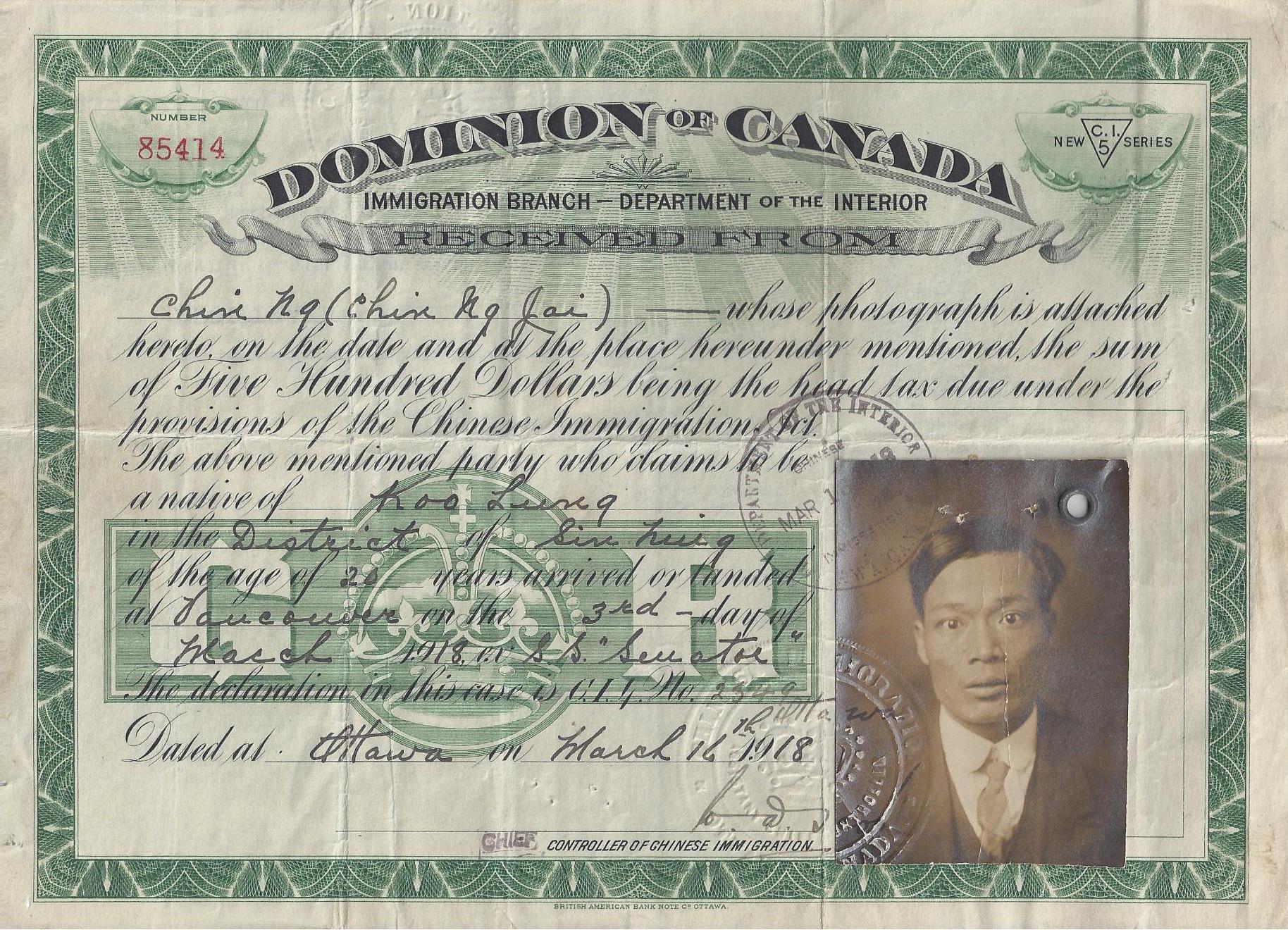

Chinese migration was particularly targeted. Measures like the Chinese head tax, landing taxes, bilateral restriction agreements and other travel restrictions virtually prohibited Chinese immigration into Canada. (See also Chinese Immigration Act.) Canadian authorities also refused to allow the settlement of female Chinese immigrants. The government feared this would encourage Chinese men, who were temporarily in Canada as railway or mine labourers, to settle down permanently. There were widespread racist fears of a supposed "yellow peril" that would endanger Canadian society’s moral fabric.

In 1914, almost 400 Indian migrants aboard the ship Komagata Maru languished in Vancouver harbour while Canadian authorities debated what to do with them. Despite being subjects of the British Empire, the passengers had exposed Canada’s racist restrictions imposed on South Asian migration. Canada's new navy, in action for the first time, escorted the ship from Canadian waters while many Vancouver residents cheered approvingly from shore. Many of the passengers would be later killed when back in India.

During the First World War, anti-German hysteria erupted in Canada. This xenophobic hostility was largely directed against those with ties to enemy countries. Although foreigners with links to countries allied to Canada were also targeted. Despite Canadian military manpower needs, British and Canadian authorities alike felt that, where possible, foreigners belonged in foreign armies. Groups such as Italians, Serbians, Poles, and some Jews were encouraged to return to the armies of their mother country or were recruited into specific British army units reserved for allied foreigners of various origins. Without national armies of their own to join, many Jews, Macedonians, and Ukrainians volunteered for the Canadian Army.

In 1910–11, rumours spread that a group of Black people was preparing to migrate to central Alberta. Descendants of previously enslaved people, they were being pushed from their lands in Oklahoma territory, where they had been granted holdings and hoped to build new lives.

Public and political response in Alberta was immediate and predictable. Federal authorities initiated an ingeniously simple scheme. Nothing in the Immigration Act specifically barred Black Americans, but any immigrant could effectively be denied access to Canada for health reasons under the Act's medical provisions. The government merely instructed immigration inspectors and their medical aides along the American border to reject all Blacks as unfit for admission on medical grounds. There was no appeal. Blacks were warned they should not waste their time and money by considering immigration to Canada. (See also Order-in-Council P.C. 1911–1324.)

As a result of the devastating economic collapse caused by the Great Depression, the government's approach to immigration hardened. Immigration authorities switched to actively preventing migration into Canada. By 1933, Hitler ruled Germany, and millions of political opponents and Jews might have survived if Canada or other countries had offered innocent victims a home. Although many Canadians responded to the refugees with a mixture of sympathy for their desperate plight and embarrassment at the lack of government aid, others, including the federal Cabinet, many in the diplomatic corps, and immigration policymakers, reacted with alarm to any pressure to accept Jews or political refugees escaping Germany. As a result, few refugees were able to get around Canadian immigration restrictions. (See also MS. St. Louis.)

Dismantling Racial and Ethnic Barriers

At war's end in 1945, Canadian immigration regulations remained unchanged from the restrictive pre-war years. Yet change was not long in coming. Driven by a postwar economic boom, growing job market, and a resulting demand for labour, Canada gradually re-opened its doors to European immigration. Initially, to immigrants Canada traditionally preferred — those from the United Kingdom and Western Europe — but eventually to the rest of Europe as well. However, with the onset of the Cold War, immigration from Eastern Europe came to a halt. Borders to the west were closed by the Soviet Union and its allies. However, large numbers of immigrants entered Canada from southern Europe, particularly Italy, Greece and Portugal.

Unlike immigration from previous decades, postwar immigration was not streamed exclusively into agricultural or rural-based resource extractive industries. Canada emerged from the Second World War as an urban, industrial power, and many postwar immigrants soon filled jobs in the manufacturing and construction sectors. Some helped expand city infrastructure while others — like the better-educated immigrants — met the strong demand for trained and skilled professionals.

Canadian immigration underwent other dramatic changes in the postwar years. Canadian governments, federal and provincial, slowly yielded to pressure for human rights reform from an earlier generation of immigrants and their children. Increasingly middle class and politically active, the now well-integrated immigrants had sacrificed in common cause with other Canadians in the war effort; as such, in the postwar era, they refused to assume second-class status in a country they had helped protect. Supported by like-minded Canadians, they denounced the ethnic and racial discrimination against them and demanded human rights reform. They forced governments to legislate against discrimination on account of race, religion, and origin in such areas as employment, accommodation and education. And, just as Canada was making discrimination illegal at home, the government moved to gradually eliminate racial, religious or ethnic barriers to Canadian immigration.

By the late 1960s, overt racial discrimination in immigration policy was gone from Canadian immigration legislation and regulations. This opened Canada's doors to many of those who would previously have been rejected as being “undesirable” on the basis of race or ethnicity. In 1971, for the first time in Canadian history, the majority of those immigrating into Canada were of non-European ancestry. This has been the case every year since.

Immigration Point System

That does not mean that anyone who wishes to enter Canada may do so. While restrictions on account of race or national origin are gone, Canada still maintains strict criteria for determining who is and who is not a desirable candidate for Canadian entry. In the late 1960s, Canada introduced a point system to set merit-based standards for individuals applying to immigrate to Canada.

Under this system, each applicant is awarded points for age, education, ability to speak English or French, and demand for that particular applicant's job skills. If an applicant was in good health and of good character in addition to scoring enough points, they were granted admission together with their spouse and dependent children. Those who did not score enough points were denied admission. More recently, Canada has modified its procedures to give preference to the admission of independent, skilled, and immediately employable immigrants.

Once established in Canada, most new arrivals — now called a "landed immigrant" — receive all the rights of a Canadian citizen except notably the right to vote. After a specified number of years of residing in Canada (currently three years out of five), each landed immigrant may apply for Canadian citizenship. In addition, landed immigrants, like Canadian citizens, may also apply to sponsor the admission to Canada of close family members who might not otherwise be able to satisfy stringent Canadian admission criteria. The sponsor must agree to ensure anyone brought into Canada will not become an economic burden to Canadian society. For many years, sponsored families of those already in Canada were the single largest group of those admitted into Canada. (See Family Reunification in Canada.)

Refugee Migration After 1945

Since the end of the Second World War, refugees and others dispossessed by war and violence have become a significant part of Canada's immigration flow. In the postwar labour shortage, Canada admitted tens of thousands of displaced persons. Many had been made homeless by the war or who, at war's end, found themselves outside of their country of citizenship, to which they refused to return. Among the displaced persons were Jewish Holocaust survivors who had no community or family to which they could return. Other displaced persons refused repatriation back to countries which had fallen under Soviet domination. Many resettled in Canada, where they built new lives.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Canada also responded to the plight of refugees from other countries that were under dictatorships. In the aftermath of the unsuccessful Hungarian uprising of 1956 and the crushing of political reform in Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union in 1968, refugees fled westward. Canada responded by setting aside its normal immigration procedures to admit its share of refugees. In the years that followed, Canada again made special allowance for refugees from political upheavals in Uganda, Chile and elsewhere. (See also Latin Americans.) In each of these cases, the refugees were admitted as an exception to the immigration regulations and without following all of the usual immigration procedures.

In 1978, Canada enacted a new Immigration Act that, for the first time, affirmed Canada's commitment to the resettlement of refugees from oppression. Namely, individuals who have a well-founded fear of persecution in their country of citizenship. Accordingly, refugees would no longer be admitted to Canada as an exception to immigration regulations. Admission of refugees was now part of Canadian immigration law and regulations. But refugee admission has remained controversial and difficult to administer. (See also Canadian Refugee Policy.)

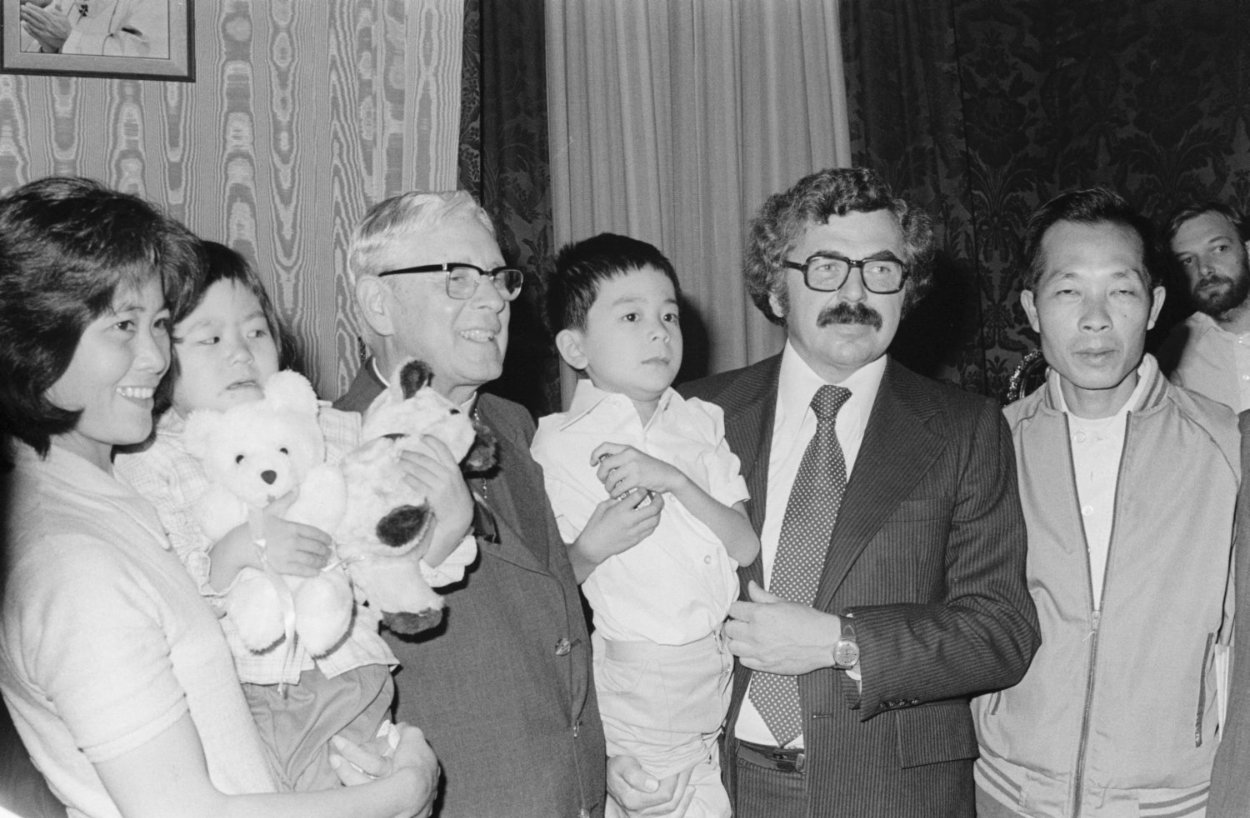

The first major refugee resettlement program under this new legislation was during the early 1980s, when Canada led the Western world in its welcome to Southeast Asian refugees and particularly those from Vietnam, often referred to as the "boat people." Many of the boat people were selected from among those who escaped Vietnam in tiny boats and eventually found themselves confined to refugee camps in Thailand or Hong Kong awaiting permanent homes. (See also Canadian Response to the “Boat People” Refugee Crisis.)

Some people seeking protection are not selected by immigration officials, but instead come to Canada to apply for refugee status. These “asylum seekers” sometimes arrived to Canada after disembarking from flights between Eastern Europe and Cuba that land to refuel in Gander, Newfoundland. Many of them sought to escape the horror of war and persecution in Central America, Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and China to seek sanctuary in Canada. Once in Canada, asylum seekers must prove to Canadian officials that they were are being persecuted in their homeland. If refugee status is granted, they may stay in Canada; otherwise, claimants may be deported.

Immigration in the Late 20th Century

In the 1980s, the number of those entering Canada and applying for refugee status grew, and the Canadian determination process was hard-pressed to process applicants quickly. Nor were refugee claimants universally welcomed by Canadians. Some Canadians worried that many of the refugee claimants were not really legitimate refugees but individuals looking for a way around tough Canadian immigration regulations.

The refugee issue was dramatically brought home to Canadians in the late 1980s, when two ships illegally stranded their respective cargoes of Sikh (see Sikhism) and Tamil refugee claimants on Canada's east coast. Amid greatly exaggerated fears that Canada was about to be “flooded” with refugees, Parliament and immigration authorities began tightening refugee regulations and procedures. The result has been a continual streamlining or hardening of the Canadian refugee determination process. Canadian authorities have also been working closely with other countries and transportation companies to make it more difficult for individuals who might make a refugee claim to reach Canada. Some Canadians are concerned that these changes mean that some legitimate refugees are now being denied sanctuary they are entitled to under international law.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, even as it was seeking to forestall the entry of would-be refugee claimants, Canada opened new avenues for other immigrants with employable skills or significant financial resources. Beginning during the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney, those with capital or skills necessary to invest and start businesses within Canada were invited to apply for Canadian immigration. The idea was that these initiatives would help create employment and wealth in Canada.

As a result, the number of entrepreneurial or business immigrants rose dramatically, reaching 6 per cent of all immigrants entering Canada. A good number of entrepreneurial-class immigrants came from Hong Kong, many seeking a safe harbour for themselves, their families, and their assets in advance of the Chinese takeover of Hong Kong in 1997. It was natural that many should respond to Canada's invitation and the opportunities offered for capital investment in Canada. As a result, Canada became a prime destination for Hong Kong and other Chinese immigration and for capital in flight. Between 1981 and 1983, Chinese immigrants invested $1.1 billion in the Canadian economy. Hong Kong and other Chinese immigration has been especially pronounced in larger urban areas such as Vancouver and Toronto, where the Chinese community now constitutes the largest immigrant group. However, most of these entrepreneurial-class immigrants did not arrive speaking English or French, and this prompted the Canadian government to introduce tougher language requirements for those coming to Canada.

Immigration from Africa (mainly from South Africa, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Kenya, Ghana, Uganda, and Nigeria) also grew in the 1980s and 1990s. Some of these newcomers were professionals with academic qualifications seeking better working conditions in Canada. The vast majority, however, were refugees fleeing war, famine, and political and economic instability in their countries of origin.

With the economic slowdown of the 1990s, Canadian immigration re-emerged as a topic of public debate. This was only natural, given the continuing impact of immigration on Canadian society. While many economists argue that Canada, with its relatively low birth rate and aging population, needs the infusion of population, energy, skills, capital and buying power that immigrants bring to Canada. Some continue to harbour doubts, however.

With immigrants of non-European origin making up a large majority of those entering Canada, some Canadians have expressed uneasiness at the changing character of urban Canada. However, many of these prejudices towards Canadians of other ethnic and racial origins often tend to be exaggerated and harm minority communities.

Public debate on immigration in Canada has remained civil and has certainly been free of the kind of violence that the arrival of large numbers of immigrants has provoked in France and Germany.

Canadian Immigration since 11 September 2001

As a direct consequence of the events of 11 September 2001, the terrorist threat, and security issues, Canada has tightened its immigration policy. (See also 9/11 and Canada.) In 2002, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) was passed. The new law replaced the 1976 Immigration Act. It notably made immigration into Canada harder, including for refugees. However, the Act did also make it easier for people in common-law or same-sex relationships to enter Canada.

Canada’s harsher stance on refugee migration was reflected in how it treated Tamil asylum seekers in 2009–2010. Seen as “bogus” refugees, many were imprisoned despite being legitimate refugees. Many Canadians reacted similarly to asylum seekers performing irregular crossings of the US-Canada border to seek protection in Canada. (See also Canada-United States Safe Third Country Agreement.) This was despite the fact that it is an internationally recognized human right to claim asylum in another country.

These attitudes stood in stark contrast to the Canadian response to the Syrian refugee crisis. Between 2015 and 2017, Canada rapidly resettled 54,000 Syrian refugees. While this number was greater than the US’, Canada’s contribution paled in comparison to other countries like Germany, Lebanon, Turkey, and Sweden.

Modern-Day Immigration to Canada

Canada receives a considerable number of immigrants every year. From 2001 to 2014, an average of around 249,500 landed immigrants settled in Canada every year. In 2015, more than 271,800 migrants were admitted while this number increased to over 296,300 in 2016.

Between 2016 and 2021, Canada welcomed a bit over 1.3 million immigrants. Census data from 2021 shows that migrants from India, the Philippines and China were the three most numerous groups of recent immigrants arriving in Canada. Around 18.6 per cent of recent immigrants were born in India, 11.4 per cent in the Philippines and 8.9 per cent in China. (See South Asian Canadians; Filipino Canadians; Chinese Canadians.) Other major groups of immigrants originated from Syria (4.8 per cent), Nigeria (3 per cent), the United States (3 per cent), Pakistan (2.7 per cent), France (2 per cent), Iran (1.9 per cent) and the United Kingdom (1.7 per cent).

Take the quiz!

Test your knowledge of multiculturalism in Canada by taking this quiz, offered by the Citizenship Challenge! A program of Historica Canada, the Citizenship Challenge invites Canadians to test their national knowledge by taking a mock citizenship exam, as well as other themed quizzes.

The vast majority of newcomers (88.7 per cent) settled in four provinces: Ontario (44 per cent), Quebec (15.3 per cent), British Columbia (14.9 per cent) and Alberta (14.5 per cent). Most of them also live in these provinces’ major urban centres like Toronto (29.5 per cent), Montreal (12.2 per cent) and Vancouver (11.7 per cent). These three cities alone receive over half of all recent immigrants. Although, this percentage has gone down as immigrants settled in other urban centres.

According to the 2021 census, Canadians originally born outside of Canada made up 23 per cent (8.3 million people) of the Canadian population ― a record-high proportion since 1921. Canada has the highest proportion of immigrants among G7 countries. (See Canada and the G7.)

Modern Canada was built on the migration and contributions of many immigrant groups, beginning with the first French settlers, through newcomers from the United Kingdom, Central Europe, the Caribbean and Africa, to immigrants from Asia and the Middle East. While the challenges posed by racism and discrimination remain, Canadian society remains generally open to immigration. Moreover, many immigrants’ contribution to Canadian society and desire to help build a better society on Canadian soil is beyond dispute.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom