Thorfinn Karlsefni (Old Norse Þórfinnr Karlsefni), explorer and trader (born c. 980–95 CE in Iceland; year of death unknown). Born Thorfinn Thordarson, this Icelandic aristocrat and wealthy merchant ship owner led one of the Norse expeditions to Vinland, located in what is now Atlantic Canada. He is usually referred to by his nickname, Karlsefni, meaning “the makings of a man.” Karlsefni appears in several historical sources. A long passage in The Saga of the Greenlanders is devoted to him, and he is the chief subject of The Saga of Erik the Red. There are also short accounts in the Old Norse manuscripts known as the Arni Magnusson codex 770b and Vellum codex No. 192.

Statue of Thorfinn Karlsefni by Icelandic sculptor Einar Jónsson in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Photo taken in 2009. (Courtesy Michael W Murphy/flickr CC)

Note on Abbreviations

In this article, The Saga of the Greenlanders (Grœnlendinga saga in Old Norse) is abbreviated to GS. The Saga of Erik the Red (Eiríks saga rauða in Old Norse) is abbreviated to ES.

Early Life and Career

Little is known about Karlsefni’s early years except that he belonged to a wealthy family descended from several kings, among them Olaf the White of Dublin and his wife, Aud the Deep-Minded. Karlsefni’s father was named Thord Horsehead. Although the sagas don’t completely agree on the details, the family is likely to have owned a large estate called Reynisnes, located in Skagafjord in northern Iceland. Karlsefni is generally considered to have been born around 980 CE, but at least one scholar of the Icelandic sagas has made the case that he was born closer to 995.

In adulthood, Karlsefni acquired a share in an ocean-going trading ship and began trading goods between Iceland and Norway.

Increasing his trading sphere to Greenland, Karlsefni arrived at Erik the Red’s settlement, Brattahlid, with his business partner, Snorri Thorbrandsson, and a crew of 40 manning a ship full of goods. He spent the winter with Erik and became enamoured with Erik’s widowed daughter-in-law, Gudrid, a native of Iceland noted for her knowledge and beauty. He obtained permission to marry her from Erik, according to ES, but from Erik’s son Leif according to GS. The wedding took place at Brattahlid, probably sometime after the year 1010.

In Greenland, there was much talk about the great resources of Vinland, the “Land of Wine” on the east coast of North America. Leif Eriksson had explored it, and Karlsefni was encouraged to go. From this point on in the sagas, there are two versions of what happened.

Statue of Leif Eriksson in Qassiarsuk, Greenland, the site of Brattahlid during Norse colonization. Photo taken in 2011. (Courtesy claire rowland/flickr CC).

Conflicting Stories

In GS, Karlsefni’s Vinland expedition is just one of four separate trips. However, ES combines the four expeditions into one large journey led by Karlsefni. The ES journey consists of three ships and a crew of 140, including Leif’s siblings Thorvald and Freydis (who in GS led their own expeditions). The role of Leif Eriksson, otherwise acknowledged as the first non-Indigenous person to explore and name the area he called Vinland, is reduced. In a short passage, Leif is storm-driven to Vinland and reports its resources: self-sown wheat, grapes, lumber and burl wood, which the Norse prized for its intricate ring patterns.

There is little doubt that GS is the more trustworthy of the two sources. The change in the story from one saga to the other appears to owe to an attempt, around 1200, to have Karlsefni and Gudrid’s great-grandson, Bishop Björn Gílsson, declared a saint. Glorious ancestors such as these Vinland-farers were needed to support the canonization, so their role was magnified.

Exploration of Vinland

Aside from their conflicting accounts of the number of expeditions and who led them, the two sagas describe mostly the same events. In both sources, Karlsefni and Gudrid spend three summers in Vinland, arriving during the first and leaving during the third. Their son Snorri is born in Vinland — the first person of European descent born on North American soil.

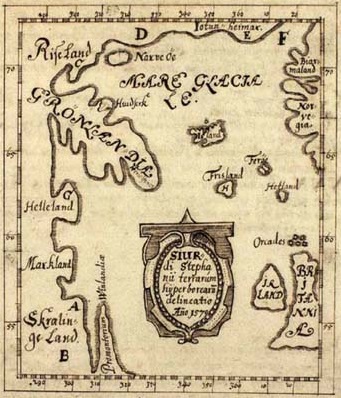

In GS, Karlsefni uses Leifsbúðir, Leif’s Camp, as his base. Leif emphasizes that Karlsefni can use it, but that it remains Leif’s property. In ES, however, Karlsefni assumes much of Leif’s role as explorer of Vinland. Karlsefni’s story also describes areas to the north, Markland and Helluland, in terms that echo those attributed to Leif in GS. A fine difference is that while GS clearly states that Leif is the one who bestows these names, ES subtly avoids attributing them to Karlsefni or Leif. One sign that others had come before Karlsefni’s expedition is that he and his crew observe a ship’s keel on a headland, the same keel described in GS as having been placed by a previous expedition.

In ES, Karlsefni establishes his own base somewhere not too far south of Markland. He calls it Straumfjord (Fjord of Currents) after the strong currents around an island at the mouth of the fjord. Some scholars have argued that the Norse base discovered at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland is Straumfjord.

After the first winter, the company of the expedition divides into two exploration groups. One goes north and the other, consisting of 40 men led by Karlsefni, heads south. After a long time, they arrive at a place where there are wide sandbars at the mouth of a river that make it impossible to enter the river except at high tide. They set up camp on the shore of this lagoon and call the place Hóp (Tidal Lagoon). It is an abundant landscape, with fields of self-sown wheat in the low-lying areas, and grapes growing in copses of trees. Every stream has many fish, and the Norsemen catch halibut in tidal pools (see also Flatfish). There are plenty of animals in the forest.

Hóp did not become a real settlement, only a summer base, and the Hauk’s Book version of ES says that Karlsefni spent only two summer months there with his 40 men while the rest of the party remained at Straumfjord.

Encounters with Indigenous People

The sagas’ stories about Karlsefni are notable for their vivid descriptions of meetings with the Indigenous inhabitants of the land, whom the Norse termed Skrælings (likely a derogatory name). They could have been ancestors of the Mi’kmaq, the Beothuk, the Innu or other East Coast Indigenous peoples.

The first encounter is peaceful. The Indigenous people arrive in hide-covered canoes and come ashore. Each party is as astonished as the other. They return a second time, carrying packs of fine furs. A trade begins, the Norse offering milk or red cloth in return for the pelts. Soon a fight breaks out, and people are killed on both sides. Karlsefni recognizes that despite everything the land has to offer, the Norse would constantly fear an attack from the people who already live there. They return to Straumfjord, where they spend the winter.

At winter’s end, they begin preparations for the return to Greenland and arrive in Eriksfjord with a valuable load of grapes, wood and furs. On the way, they capture two Indigenous boys from a party of five people they encounter in Markland. These children are later baptized and taught the Norse language in Greenland.

Karlsefni and Gudrid spend the next winter with Erik the Red, and finally return to Iceland the following summer to settle at his family estate, Reynisnes.

Did you know?

The Norse divided the year into two seasons, winter and summer. Winter began around October 14 and summer began around April 14. A person’s age was measured in winters. The further division of the year into months was based on activities such as harvesting, butchering and sowing. The Norse expressed times of the day with facts (e.g., míðdegi, mid-day) or defined them by meals (e.g., dagmál, day-meal). Telling time involved reading local solar and lunar positions and was not precise.

Family and Later Life

Karlsefni’s family was prominent in Iceland. The Saga of Erik the Red says that his mother considered Gudrid too low in social status to marry to her son. Gudrid was not even allowed on the family estate the first winter of their return to Iceland. As Karlsefni’s mother got to know Gudrid, she changed her mind, and the two became fast friends.

Karlsefni and Gudrid’s sons, Snorri and Thorbjorn, have a long line of prominent descendants, among them several important bishops and the abbess of a nunnery founded in 1295 on the family estate. Their descendants also include Law Speaker Hauk Erlendsson (c. 1264–1334), who served as the highest elected official of Icelandic parliament. Hauk compiled and partially copied out the Hauk’s Book version of ES by hand. He may even have made additions based on family oral history. A genealogical list added to the end of the saga traces the family to Hauk himself.

The sagas say little of Karlsefni’s later life. A brief passage in GS does, however, touch on his trading business following the Vinland expedition. Karslefni and Gudrid sail to Norway with their valuable cargo, and a German pays a mark of gold for a wooden decoration made from Vinland burl wood.

After Karlsefni’s death, the management of the family estate fell to Gudrid and Snorri.

Significance

Few personal details are known about Karlsefni, but his family background and wealth made him a person of influence. During Karlsefni’s first winter in Greenland, when Erik the Red ran out of provisions and beer for a Yuletide (Christmas) celebration befitting a chieftain, Karlsefni offered him everything needed from the supplies he brought. The gesture increased Karlsefni’s influence and contributed to the reputation on which his authority rested.

His successful expedition to Vinland added to his fame. Although he shared both his ship and trading ventures with a partner, fellow Icelander Snorri Thorbrandsson, Karlsefni is more renowned, probably because of the later significance of his family.

Karlsefni and Gudrid’s son Snorri was the first person of European descent born in North America.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom