Leif Eriksson (Old Norse Leifr Eiríksson, a.k.a. Leifr hinn heppni, Leif the Lucky), explorer, chieftain (born in the 970s CE in Iceland; died between 1018 and 1025 in Greenland). Leif Eriksson was the first European to explore the east coast of North America, including areas that are now part of Arctic and Atlantic Canada. Upon the death of his father, Erik the Red, Leif became paramount chieftain of the Norse colony in Greenland. The two main sources on him are The Saga of the Greenlanders and The Saga of Erik the Red. There are also references to him in The Saga of Olaf Tryggvason and The Saga of St. Olaf.

Early Life and Education

Leif Eriksson was one of three sons born to Erik the Red — the first colonizer of Greenland — and his wife, Thjodhild. Leif moved with his parents from Iceland to Greenland around the year 985. In the 990s, Leif presented himself at the court of King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, who “showed him much honour, as Leif appeared to him to be a man of good breeding.” To serve a respected ruler was part of the education of any well-bred young Norseman.

According to some sources, Leif converted to Christianity at Olaf’s urging, and when Leif announced his intention to return to Greenland, Olaf provided him with a priest and other clergy and commanded him to introduce Christianity there. Many scholars have doubted this early event, believing that it would have taken place a decade or more after the year 1000. However, archaeological evidence from the Greenland colony has indicated the existence of a Christian church and a surrounding cemetery where people were buried beginning in the 990s. Leif’s own beliefs aside, the bond of loyalty between him and Olaf — and the status Leif would have gained by having the king’s support — are enough to explain why he might have undertaken the religious mission.

Explorations

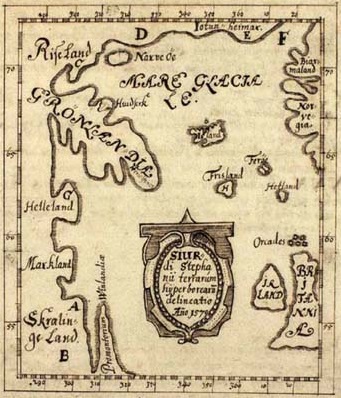

Leif is best known for his explorations in North America, which he undertook around the year 1000. The stories of his role vary. In The Saga of the Greenlanders, which survives only in a manuscript written in 1387, Leif decides to explore areas observed by the Icelander Bjarni Herjolfsson fifteen years earlier, when Bjarni’s ship blew off course on its way from Iceland to Greenland. Bjarni had observed three areas, which, from north to south, Leif named Helluland, Markland and Vínland.

Helluland, meaning Land of Stone Slabs, was a landscape of glaciers, mountains and rock. It is thought to be the area from Baffin Island and Resolution Island in Nunavut to the Torngat Mountains in northern Labrador. Farther south was Markland (Land of Forests), which was probably a large region around Hamilton Inlet in central Labrador. South of Markland, around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, was Vinland (Land of Wine), so named because the Norse explorers discovered wild grapes there.

In The Saga of the Greenlanders, Leif establishes a base for further exploration in Vinland, calling it Leifsbúðir (Leif’s Camp). The exact location of this camp remains a topic of debate among scholars, some of whom have proposed that it is L’Anse aux Meadows in northern Newfoundland.

The Vinland sagas contain several vivid scenes of encounters with Indigenous peoples who would have been ancestors of the Mi’kmaq, the Beothuk and the Innu. It is unclear, however, whether Leif was present during any of these encounters, in part because the stories have been conflated and woven into each other.

The Saga of Erik the Red, written in the early 14th century, reduces Leif’s role in favour of Icelander Thorfinn Karlsefni. Thorfinn assumes Leif’s role as explorer, and the saga names Leif, rather than Bjarni, as the sailor who was blown within sight of North America in a storm. Leif’s travels become condensed into a couple of confused sentences listing the main resources of Vinland: grapes, fine lumber and self-sown wheat fields. The change in the story was intentional. This version was written to boost the reputation of Thorfinn Karlsefni and his wife, Gudrid, for the glory of their descendants.

(See also Norse Voyages.)

Leadership and Chieftainship

Leif is described in The Saga of the Greenlanders as having all the qualities that define the Norse ideal of a leader: “tall and strong, of striking appearance, shrewd, and in every aspect moderate and wise.” He became “very wealthy and was held in much respect.” Even his eyesight was better than most. On his return to Greenland from Vinland, he spotted 15 men shipwrecked on a reef well before his crew could see them. He showed the shipwrecked men hospitality befitting a leader, organizing lodgings for the group and inviting their leader and his family to spend the winter with him. After this, Leif was called Leif the Lucky (Leifr hinn heppni).

Did you know?

In Old Norse, heppin does not stand for luck in the contemporary sense of the word. According to Nordic mythology specialist Bettina Sejbjerg Sommer, it refers to “a quality inherent in the man and his lineage, a part of his personality similar to his strength, intelligence, or skill with weapons, at once both the cause and the expression of the success, wealth, and power of a family … a hero was a man of luck.” In the minds of the Norse, Leif was not “lucky” because of his accomplishments. It was the other way around. He managed to do what he did because of his happ, his luck.

Upon the death of his father, Erik, shortly after 1000 CE, Leif took over the family estate at Brattahlid, Greenland. He became paramount chieftain of the colony Erik had founded. Leif never revisited Vinland as chieftain, but he authorized members of his family to seek it out.

Leif was still alive in 1018 when, according to The Saga of St. Olaf, King Olaf II sent his conquered adversary Hraerik “to Leif Eriksson in Greenland.” Olaf hoped that the colony’s remoteness would ensure that Hraerik would never return. By roughly 1025, Leif was dead and his son Thorkell was the chieftain at Brattahlid, according to The Saga of the Sworn Brothers. Brattahlid continued to be the paramount chieftain seat, but it is not known whether Leif’s descendants continued as leaders.

Personal Life

Leif’s wife is not mentioned in any source, and little is known about his descendants except that he had two sons. One, named Thorgils, was conceived out of wedlock in the Hebrides (a series of islands off the west coast of Scotland) during Leif’s early voyage to Norway. Thorgils’s mother was Thorgunna, a Hebridean noblewoman. While Leif acknowledged Thorgils as his son, he refused to marry Thorgunna — a slight that she suggested Thorgils would repay when he came of age: “it’s my guess that he will serve you as well as you have served me now with your departure.” She eventually sent Thorgils to Greenland, where people viewed him as having something strange about him. Leif’s other son, Thorkell, was presumably born to Leif and his wife, making him the legitimate heir to Brattahlid and the chieftainship.

Significance

Leif Eriksson was the first European to explore what is now eastern Canada, from the Arctic to New Brunswick, around 1000 CE. He made these voyages nearly five hundred years before Christopher Columbus’s journey across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492. Today, efforts by archaeologists to conclusively establish the location of Leif’s short-lived base in Vinland are ongoing.

A statue of Leif Eriksson in Reykjavik, Iceland. Photo taken in 2016. (Courtesy Plashing Vole/flickr CC)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom