Michel Sarrazin, surgeon, physician, naturalist (born September 1659 in Nuits-sous-Beaune, France; died 8 September 1734 in Quebec City). Sarrazin came to New France as a ship surgeon in 1685 or 1686 and became head physician of New France by 1699. He conducted what was probably the first mastectomy in North America. Sarrazin was also interested in botany and was among the first to catalogue North American plants and animals, including several plants previously unknown to Europeans.

Early Life

Michel Sarrazin was born in Nuits-sous-Beaune (now Nuits-Saint-Georges) in the Burgundy region of France and was baptized on 3 September 1659. His parents were Magdelaine (Madeleine) de Bonnefoy and Claude Sarrazin, an abbey official at Cîteaux Abbey. Michel was one of six children, although only two brothers are known to have survived into adulthood. Details of his early life remain obscure; he possibly trained as a surgeon in Paris.

Surgeon-Major in New France

In 1685 or 1686, Michel Sarrazin sailed to New France as a marine surgeon. In 1686, the colony’s governor-general, Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville, and intendant, Jean Bochart de Champigny, appointed Sarrazin surgeon-major of the colonial troops. He was the first to hold this position in New France.

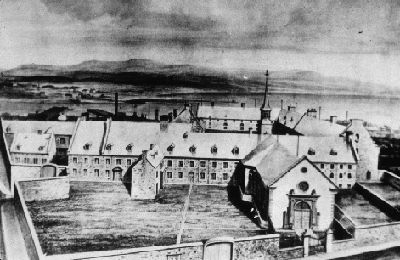

As surgeon-major, Sarrazin accompanied military expeditions but was also permitted to serve the general population and clergy. He treated patients at the Hôtel-Dieu in Montreal and, starting in 1693, also in Quebec City. The Sovereign Council, the colony’s parliament, occasionally called on him for medical advice as well.

Head Physician of New France

In 1694, Michel Sarrazin traveled back to France to obtain a medical degree from the University of Reims. He returned to Quebec in 1697 with the title ‘royal physician’ and became head physician of New France by 1699. At the same time, he continued to practice surgery. In 1700, he conducted the first mastectomy on record in North America, one of the most difficult procedures of the time. It was successful: the patient lived until 1739.

Sarrazin’s situation was unusual, as physicians and surgeons were trained differently and belonged to different social strata in the early modern period. Physicians were university educated but had little, if any, practical training. Conversely, surgery was considered a trade that required apprenticeship but no formal academic education. By the end of the 17th century, however, surgery had increased in prestige, particularly in France, and there was increasing emphasis on clinical observation and anatomical research in medicine.

Sarrazin exemplifies this shift. He was interested in anatomy and owned books on current medical research and innovations. This indicates his openness to new approaches, also demonstrated by his use of Indigenous knowledge about medicinal plants.

Botanist and Zoologist

While in France (1694–97), Michel Sarrazin met Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, a member of the French Academy of Sciences and professor of botany at the Jardin de Roi in Paris. Their acquaintance sparked Sarrazin’s interest in the study of plants. In 1699, Sarrazin became the first official correspondent to the Academy in New France. For the next 30 years, he conducted numerous naturalist expeditions, struggling with short growing seasons, adverse climate, long distances and conflicts with Indigenous groups. He sent regular reports to Tournefort and other Academy scientists, along with seeds and plant specimens, some of which were planted in the royal gardens.

Plants with medicinal uses were of particular interest to Sarrazin. Among the first species he identified and categorized were the Canadian pitcher plant, an Indigenous remedy against smallpox (named Sarracenia purpurea in his honour), and two varieties of ginseng. He also documented maple syrup production as practiced by Indigenous populations. Moreover, he provided detailed dissection reports for Canadian mammals: beaver, muskrat, wolverine, seal and porcupine. His findings were published by the Academy, though not always under his name, and as part of catalogues compiled by other scientists.

Personal and Social Life

As head physician, Michel Sarrazin enjoyed high social status and was well connected. In 1706, the governor of New France, Marquis Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, nominated him to the Superior Council (formerly the Sovereign Council), which Sarrazin joined as a member for life on 30 June 1707. This gave him a voice in the administration of the colony.

In 1709, Sarrazin traveled to France once more and stayed for over a year, apparently for health reasons. Back in New France, aged 52, he married 20-year-old Marie-Anne Hazeur on 20 June 1712. She was the daughter of a prominent entrepreneur, seigneur (landowner) and politician. Through the marriage, Sarrazin gained some lands in the Gaspé Peninsula and the status of grand seigneur. The couple had seven children, three of whom died in infancy; only one, daughter Charlotte Louise Angélique, had children of her own.

Financial Situation

Sarrazin secured himself an above-average income through regular petitions and complaints, supported by influential acquaintances. His annual salary from the Crown more than quintupled between 1698 and 1716. He also acquired property and made — albeit unsuccessful — business investments. While earlier biographers attest Sarrazin’s financial struggles, recent accounts indicate that his material position was comfortable, even prosperous.

Death and Legacy

Michel Sarrazin died in Quebec City on 8 September 1734, at the age of 75, of a fever contracted from a patient. His 50-year legacy as a medical authority was an empirical approach, combining the hands-on methods of surgery with anatomical knowledge and intellectual inference. In science, his observations, dissections and detailed descriptions contributed to the modern classification system of plants and to an understanding of the flora and fauna of Quebec in particular. They also had an economic impact, facilitating industries such as the fur trade and maple syrup production.

Today, three institutions commemorate Sarrazin: the Maison Michel-Sarrazin, a private palliative care hospital in Quebec City; the Club de Recherches Clinique du Québec, which recognizes the contributions of Quebec researchers through its Michel Sarrazin Award; and the Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario Mille-Îles, which offers a Michel Sarrazin Prize for the best French-language science project in the Thousand Islands region in Ontario.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom