The Ojibwe (also Ojibwa and Ojibway) are an Indigenous people in Canada and the United States who are part of a larger cultural group known as the Anishinaabeg. Chippewa and Saulteaux people are also part of the Ojibwe and Anishinaabe ethnic groups. The Ojibwe are closely related to the Odawa and Algonquin peoples, and share many traditions with neighbouring Cree people, especially in the north and west of Ontario, and east of Manitoba. Some Cree and Ojibwe peoples have merged to form Oji-Cree communities. In their traditional homelands in the Eastern Woodlands, Ojibwe people became integral parts of the early fur trade economy. Ojibwe culture, language (Anishinaabemowin) and activism have persisted despite assimilative efforts by federal and provincial governments, and in many cases are representative of the enduring First Nations presence in Canada.

Ojibwe First Nations

The Ojibwe are part of a larger cultural group of Indigenous peoples known as the Anishinaabeg. The Ojibwe language is part of the Algonquian language family and is also known as Anishinaabemowin. As a result, the terms Anishinaabe and Ojibwe are often conflated. (See also Indigenous Languages in Canada.)

The term Ojibwe derives from Outchibou, the 17th-century name of a group living north of present-day Sault Ste Marie, Ontario. They were one of a series of closely related but distinct groups residing between northeastern Georgian Bay and eastern Lake Superior; European explorers and traders applied the term Ojibwe to these Indigenous populations. Those peoples who congregated near present-day Sault Ste Marie were also called Saulteaux, a term which is now more commonly used to describe Ojibwe people in northwest Ontario and southeast Manitoba. The Chippewa traditionally lived in parts of Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and North Dakota.

In the 17th century, Ojibwe peoples diverged from the Great Lakes area and moved into Southern Ontario, opened up by the dispersal of the Wendat, and into Wisconsin and Minnesota, where they displaced the Dakota. Later, Ojibwe people spread northward and westward in search of fur-bearing animals to supply the fur trade. In the Prairie provinces they are known as Plains Ojibwe or Saulteaux. Other groups, having merged with Cree communities, may be known as Oji-Cree, or simply Cree. Ojibwe peoples in Southern Ontario include the Nipissing, who originate from around Lake Nipissing (see also Nipissing First Nation), and the Mississauga, who moved from Manitoulin Island in the 17th century to the region which is now the present-day Greater Toronto area.

Population

It is difficult to estimate current the population of Ojibwe people living in Canada, as some people may identify as Ojibwe, but may not be registered with a specific First Nation. In terms of registered population, Ojibwe people (including Saulteaux and Mississauga) are among the most numerous in Canada. As of 2014, approximately 160,000 people make up about 200 First Nation bands.

Language

The Ojibwe language, part of the Algonquian language family, is widely spoken in Canada. Also known as Anishinaabemowin, the language has many regional dialects and as of 2011, was spoken by more than 25,000 people. Dialects like Algonquin are less commonly spoken (approximately 2,400 speakers), while Oji-Cree (a mixture of Ojibwe and Cree) is spoken by more than 10,000 people. (See also Indigenous Languages in Canada.)

Traditional Life

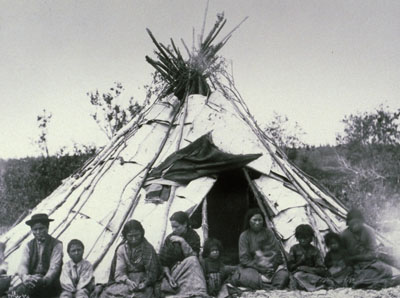

Before contact with Europeans, Ojibwe people subsisted by hunting, fishing and gathering. They resided largely in dome-shaped birchbark dwellings known as wigwams, and often made use of tipi-shaped dwellings. They wore animal-skin clothing — usually deer or moose hides — and travelled by birchbark canoe in warm weather and snowshoes in winter. Men were responsible for hunting large game, while women were responsible for tanning and processing hides into moccasins, leggings, breach cloths and dresses. Once European trade goods became common, Ojibwe people developed ornate beadwork to adorn their clothing.

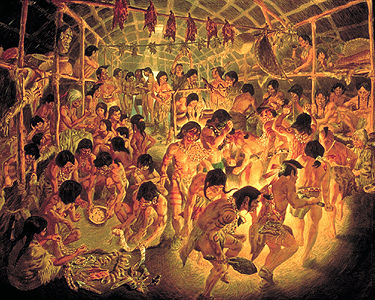

Gathering activities were largely communal, as the collection and preparation of maple sugar and wild rice are labour intensive. Maple sugar was a common seasoning, while wild rice was a staple for those who had ready access to it. Thousands of people would often convene at the site of large-scale fisheries to spear and net freshwater fish in the northern Great Lakes. These gatherings were often a time for socializing and gift-giving.

Ojibwe people were divided into independent and politically autonomous bands that shared culture, common traditions and also intermarried with each other. A band would have its own chief and hunting grounds, and would disperse into family-based hunting groups for the winter, reforming as a band in late-spring or early-summer villages.

Ojibwe society was divided into patrilineal totem-based clans, where clan members were seen as close family and therefore, intermarriage was forbidden. There were over 20 different clan doodems, or totems, including the crane, catfish, bear, marten, wolf and loon.

Spiritual Beliefs

Ojibwe oral traditions are extensive and serve both moral and entertainment purposes. The character of Nanabozo, a shape shifter of varying gender, is both creator, arranger of the earth and a trickster. Nanabozo is common across Algonquian peoples, though it may be known by different names. Other figures like the Thunderbird, Great Serpent and Mishipeshu governed various realms of the natural world. Windigo, a man-eating monster who could only be killed by a shaman, was said to roam the winter forests and feast on the flesh of men. (See also Indigenous Oral History and Primary Sources and Spirituality and Religion of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Ojibwe spiritual life was animistic, the natural world being inhabited by numerous spirits both good and evil, some of which required special treatment. The spirits that filled all life are known as the Manitou. Adolescent Ojibwe practiced spiritual quests, which produced visions and revealed guardian spirits after a period of isolation and fasting.(See also Vision Quest.) Shamans cured the ill and performed Shaking Tent rites to communicate with spirits. After about 1700, an organized priesthood among the more westerly Ojibwe created the Midewiwin, or Grand Medicine Society. This organization of shamans became a repository of Ojibwe cultural traditions, and may have been a response to pressure from Christian missionaries.

The influence of missionaries on Ojibwe spiritual life cannot be discounted, as many converted to Christianity, if only to avoid further annoyance. Some have argued that the ultimate power in Ojibwe spiritual life, Kitchi Manitou (“The Great Spirit”), was in fact a merging of traditional belief systems with those of missionaries intent on promoting Christianity.

Did You Know?

In the cultural sphere, the vibrant, pictograph-inspired Woodland School of art, typified by the spiritual work of the late Norval Morrisseau, gained prominence for Anishinaabe artists in the 1970s and 1980s. Contemporary Anishinaabe artists have entrenched themselves in the mainstream of the international art community and often use traditional imagery in installations, performance, sculpture and painting to make overt political statements about contemporary Indigenous realities.

Post-Contact Life

The European fur trade profoundly affected the Ojibwe. Initially, they traded furs for French trade items with the Nipissing and Algonquin. Following the mid-17th-century dispersal of the Wendat and other neighbouring Algonquians, the Odawa and their Ojibwe allies became middlemen between European traders and Indigenous communities farther west. The Ojibwe participated in the occasional multi-community Feasts of the Dead at which furs and trade goods were distributed. The western expansion of the French fur trade and the establishment of the English Hudson’s Bay Company near James Bay and Hudson Bay drew some Ojibwe into new areas, first as temporary trader-hunters, but later as permanent residents. Ojibwe moving north and west into traditional Cree territory often created blended communities. In some cases newcomers simply joined existing Cree communities, becoming known as Cree themselves, or established a blended Oji-Cree culture and identity.

Between 1680 and 1800, four divisions of Ojibwe emerged, each representing a different adaptation to environmental and life alongside Europeans. Those who moved south of Lake Superior into Wisconsin and Minnesota, displacing, often forcefully, the Dakota, are known as the Southwestern Chippewa. The harsher environment of the coniferous forests of northern Ontario and Manitoba was exploited by the Northern Ojibwe, which includes Oji-Cree communities.

After 1780 some shifted to Manitoba, Saskatchewan, North Dakota, Alberta and, in the case of the Saulteaux First Nation, northeastern British Columbia. These western migrants became the Plains Ojibwe, more commonly known as Saulteaux. Still others, now known as Southeastern Ojibwe, moved into south-central Ontario and the Lower Peninsula of Michigan from traditional lands along the northern shores of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay.

The social and economic life of all Ojibwe groups was affected by the fur trade. Traditional items were replaced by European-manufactured materials and certain natural resources became depleted. As Ojibwe dispersed in search of furs for trade, a major shift in subsistence activities took place. While hunters focused on trapping the more lucrative fur-bearing animals, traditional self-sufficiency through hunting suffered. As such, many Ojibwe people became partially reliant on traders for staple goods; and the ever-present threat of starvation weighed heavily.

Most Ojibwe did not sign treaties with the government until after 1850. Ojibwe chiefs in Ontario and Manitoba agreed to the Robinson and other pre-Confederation treaties as well as the post-Confederation numbered treaties, which granted colonial governments vast tracts of land in exchange for reserves, payments, and hunting and fishing rights. In many instances, the circumstances surrounding these agreements cast doubt on their legitimacy. The extinguishment of Aboriginal title and rights under these treaties is a continuing source of debate and the focus of much activism within Ojibwe and Anishinaabe communities. (See also Numbered Treaties and Upper Canada Land Surrenders.)

With the decline of traditional, subsistence ways of life, Ojibwe people became dependent on wage labour and government assistance for survival. In addition, Ojibwe people struggled with economic dependency, territorial encroachment and cultural dislocation brought about by residential schools. As local governance shifted from traditional models to those administered by the Indian Act, Ojibwe political autonomy diminished significantly. Nevertheless, Ojibwe people remain politically and culturally active.

Activism

Ojibwe communities have a strong history of political and social activism. Long before contact, they were closely aligned with Odawa and Potawatomi people in the Council of the Three Fires. From the 1870s to 1938, the Grand General Indian Council of Ontario attempted to reconcile multiple traditional models into one cohesive voice to exercise political influence over colonial legislation. In the West, 16 Plains Cree and Ojibwe bands formed the Allied Bands of Qu’Appelle in 1910 in order to redress concerns about the failure of the government to uphold Treaty 4’s promises.

Ojibwe political and social activism has continued throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. The Union of Ontario Indians represents the Anishinabek Nation and its Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi First Nations. Founded in 1949, the union advocates for the political interests of its approximately 55,000 member citizens. In 1985, the Grassy Narrows and Whitedog reserves north of Kenora won a settlement of more than $16 million over industrial waste, particularly mercury, which had contaminated drinking water and fish stocks. In 1990,Elijah Harper(Oji-Cree) helped to defeat the Meech Lake Accord by withholding his consent as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba. He opposed the Accord because it had been created without consultation or recognition of Indigenous peoples.

In 2014, Batchewana First Nation filed, along with 20 other bands in Ontario, launched a lawsuit against the governments of Ontario and Canada for not fulfilling certain clauses in the Robinson Huron Treaty. They argue that individual annuity payments of $4 have not been increased since 1874, despite a provision that amounts dispersed would reflect government earnings on the land and increase accordingly.

Did you know?

Autumn Peltier, an Indigenous girl from the Anishinabek Nation, has been fighting for water rights since the age of 8. For her efforts, at age 15, she was nominated by the David Suzuki Foundation for an International Children’s Peace Prize in September 2019. Peltier has followed in the footsteps of her grandmother, Josephine Mandamin, who also fought for Indigenous rights.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom