The Niitsitapi, sometimes referred to as the Blackfoot Nation, Blackfoot Confederacy or Siksikaitsitapi, is comprised of three Indigenous nations, the Kainai, Piikani and Siksika. The word Niitsitapi means “the real people,” . Siksikaitsitapi means “Blackfoot-speaking real people.” The traditional territory of the Niitsitapi spans parts of southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, as well as northern Montana. In the 2021 census, 18,485 people identified as having Blackfoot ancestry.

Population and Territory

The traditional territory of the Niitsitapi has been described as roughly the southern half of Alberta and Saskatchewan, and the northern portion of Montana. In the west, the Niitsitapi were bounded by the Rocky Mountains and their eastern limits stretched past the Great Sand Hills of eastern Saskatchewan. Their hunting area included the rich bison ranges of southern Alberta and northern Montana. In the 2021 census, 18,485 people identified as having Blackfoot ancestry.

Pre-colonial Life

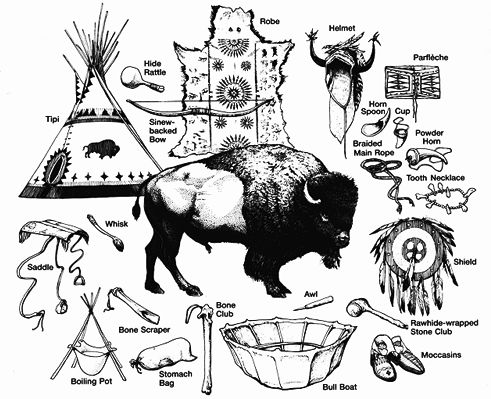

Traditional Niitsitapi culture is based on the bison hunt, intrinsically linking them to the Plains. They lived freely on the land, following bison across the plains to hunting grounds where they would utilize bison jumps and runs. Because of their portability, Niitsitapi people lived in camps sheltering in tipis. They also hunted other large game such as deer, supplementing their diet with nuts, fruits and vegetables. The bison remained the most important element of their economy, diet and way of life.

The Niitsitapi were also known for being fierce warriors with a powerful alliance system that included not only the nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy, but other nations, such as the Tsuut’ina. Warriors were revered among the people and belonged to sacred societies that honoured and tested their courage and skill. Despite significant population loss as a result of warfare, the Blackfoot Confederacy remained one of the most powerful Indigenous groups on the Northern Plains, temporarily impeding the westward expansion of European settlers.

Shining Mountains - the Ancient Ones by Guy Clarkson, National Film Board of Canada

Society and Culture

During the summer, groups would converge to hunt bison and celebrate with elaborate feasts and dances. The Sun Dance, a communal celebration held annually in mid-summer, was the central aspect of Niitsitapi cultural life. European settlers and missionaries opposed the Niitsitapi’s complex and well-established traditions. Assimilatory laws and policies were implemented in order to eradicate the expression of traditional culture (See also Indian Act and Residential Schools). However, Niitsitapi oral histories passed cultural traditions on to future generations, including participating in sweat lodges and sacred societies (such as the Horn Society).

Religion and Spirituality

Although creation stories differ between Niitsitapi communities, the Creator (also known as Old Man or N’api) was believed to be light personified and was therefore also considered to be the beginning of the day, the beginning of life. As in other Indigenous religions, the Creator is non-human and non-gendered. Old Man created and is eternally part of all the living people, creature and life forms on the earth.

Language

The Blackfoot language is part of the Algonquian linguistic group. It is spoken by the three nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy with only slight variations in dialect (see Siksikáí’powahsin: Blackfoot Language).

John William Tims, an Anglican missionary, created the Blackfoot syllabary (a type of writing system) while he lived among the Blackfoot from 1883 to 1895. Today, the syllabary is rarely used. In 1975, the Blackfoot writing system officially changed to better reflect the sounds and words of the language. The orthography (spelling system) typically uses the following:

|

Alphabet Sequences |

12 English letters: a, h, i, k, m, n, o, p, s, t, w, y |

|

Glottal Stop (the sound of making a consonant by obstructing airflow in the vocal tract) |

Represented by a single quotation mark (’) |

|

Vowels |

English letters: a, i, o |

|

Semi-vowels |

English letters w and y, which occur between vowels |

There are a few linguistic differences among the Blackfoot dialects. Lexical differences (i.e., uses of different words for the same reference, or different meanings assigned to the same word) involve words that are not part of Indigenous cultures. For example, the word for “ice cream” in Kainai is sstónniki (literally “cold milk”) and áísstoyi in Siksika (literally “that which is cold”). Dialectal grammars also have different gender divisions (i.e., masculine/feminine/neutral and animate/inanimate). For example, the word for ashtray in Kainai — iitáísapahtsimao'p — is of animate gender; in Piikani, the same word is of inanimate gender. The phonology (systems of sounds) also differs between peoples, but generally speaking, Siksika, Kainai and Piikani peoples can understand one another.

Residential schools and other cultural assimilation policies eroded traditional language usage and cultural practices. In 2021, Statistics Canada reported that 4,935 people identified the Blackfoot language as their mother tongue. In that same census, 6,585 people claimed knowledge of the Blackfoot language. Considered an endangered language, several language programs exist to promote its resurgence. Indeed, the Alberta Ministry of Education, through consultation with Niitsitapi Elders and educators, provides full curriculum support for Blackfoot language education from kindergarten to grade 12, for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

Did you know?

The Urban Society for Aboriginal Youth (USAY) has partnered with an augmented and virtual reality company called Mammoth to create Thunder VR, an immersive Blackfoot language preservation and culture learning tool. The virtual reality game, based on a Blackfoot graphic novel called Thunder, tells the ancient Blackfoot story of a man who loses his wife and must travel a great distance to challenge the spirit of Thunder (Ksistsikoom) to get her back. Thunder was developed by USAY youth and Kainai Elder Randy Bottle (Saakokoto). The high-tech game, narrated by Saakokoto, is designed to teach the endangered Blackfoot language to a new generation of learners and is being advertised as a “mash-up” of tradition and technology. USAY and Mammoth, two Calgary-based organizations, have received funding from the Government of Canada and are planning to take Thunder VR, along with 27 Oculus Go headsets, to Calgary schools in fall 2019. Thunder VR is available as a free download on Oculus Go.

Colonial History

The influence of Europeans in North America preceded contact with the Niitsitapi. Though the first European traders did not encounter Niitsitapi peoples until the mid-18th century, horses — brought to North America by the Spanish — probably reached them via trade from the west between 1725 and 1731. Around the same time, they received firearms from neighbouring Cree and Assiniboine traders. Throughout most of the 18th and 19th centuries, the equestrian Niitsitapi dominated their hunting area and were almost constantly at war with the Cree, Assiniboine, Crow, Nez Percé, Shoshone and other nations. They frequented the Hudson's Bay Company and North West Company posts on the North Saskatchewan River but fought with US trappers and free traders in the south until 1870 when American troops massacred about 173 Piikani people at Fort Ellis in present-day Montana, according to a US Military officer. Piikani witnesses claimed the dead numbered about 220 people.

The Niitsitapi population varied over this period, with estimates ranging from as high as 20,000 in 1833 and as low as 6,350 after the 1837 smallpox epidemic. From the late 18th to mid-19th century, both the Tsuut’ina and the Gros Ventre people, though culturally and linguistically distinct from the other Blackfoot Confederacy nations, were allies of the confederacy for political reasons.

Facing the reality of dwindling bison herds and increased European settlement — both encouraged by opportunistic settler governments — the Niitsitapi were faced with minimal options and sought cultural and political protection in their homelands.

Treaties

The Niitsitapi signed a treaty with the American government in 1855, and in 1877 signed Treaty 7 with the Canadian government. Most of the Piikani settled on a reserve in Montana (now known as Blackfeet Nation and consisting of 17,321 members) while the Siksika, Kainai and North Piikani nations each established reserves in southern Alberta.

By the end of the 1800s, the bison were disappearing on the plains. In addition, the reserves effectively put an end to traditional ways of life, including the bison hunt. The confederacy struggled to survive on reserves without the ability to hunt bison. Historians commonly refer to the winter of 1883–84 as the “starvation winter” because of the widespread hunger that plagued the confederacy that season.

Contemporary Life

The Niitsitapi have been able to retain much of their traditional culture in the face of adversity. Today, the Blackfoot Confederacy nations are vibrant communities that emphasize traditional culture in education, wellness and healing programs, and in other aspects of daily life. Many Niitsitapi people rely upon ranching and farming. They also operate Indigenous-owned businesses in areas like tourism, and resource extraction and management.

Politically, the Niitsitapi nations are represented through elected chiefs and councils, as well as through the Treaty 7 Management Corporation, which provides advocacy and advisory services. The Blackfoot Confederacy itself is the source of some political momentum, with yearly conferences held among member nations that aim to facilitate greater collective organization and influence. Member nations have also independently negotiated and achieved victories with provincial and federal governments with respect to self-governance, self-determination and land claims, among other issues.

In 2014, the confederacy joined other First Nations in signing the Iinii Treaty or Buffalo Treaty, including: the Blackfeet Nation (American band), Assiniboine and Gros Ventre Tribes of Fort Belknap Reservation, Assiniboine and Dakota Tribes of Fort Peck Reservation, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (see also Coast and Interior Salish), and the Tsuut'ina Nation. In 2015, the Stoney Nakoda Nation and the Samson Cree Nation also signed this “open treaty,” which is open to other First Nations from Canada and the US. Among other issues, the signatories agreed to unite the political power of Northern Plains Indigenous nations, work towards bison conservation and strengthen traditional relationships to the land. As an open treaty, the Iinii Treaty continues to expand, with more Indigenous communities, First Nations and organizations signing it.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom