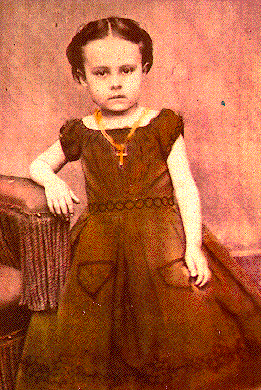

Emily Pauline Johnson (a.k.a. Tekahionwake, “double wampum”) poet, writer, artist, performer (born 10 March 1861 on the Six Nations Reserve, Canada West; died 7 March 1913 in Vancouver, BC). Pauline Johnson was one of North America’s most notable entertainers of the late 19th century. A mixed-race woman of Mohawk and European descent, she was a gifted writer and poised orator. She toured extensively, captivating audiences with her flair for the dramatic arts. Johnson made important contributions to Indigenous and Canadian oral and written culture. She is listed as a Person of National Historic Significance and her childhood home is a National Historic Site and museum. A monument in Vancouver’s Stanley Park commemorates her work and legacy. In 2016, she was one of 12 Canadian women in consideration to appear on a banknote. (See Women on Canadian Banknotes.)

Early Life and Education

Pauline Johnson was born on the Six Nations Reserve near the Grand River at Chiefswood. It was a villa near Tuscarora (also known as Middleport), located southeast of Brantford in what is now Ontario. Chiefswood served as the family home to Johnson and her three siblings — Eliza Helen, Allen Wawanosh and Henry Beverly — from 1856 to 1884. It was close to the Anglican mission where her father, George H.M. Johnson, worked. He was an interpreter and cultural negotiator between the Mohawk, the British and the Government of Canada.

Johnson suffered poor health as a child. She did not attend day school at the reserve like other Indigenous children of the time. Instead, she received an Anglican education from her mother, family members and non-Indigenous governesses. When she was 14, she began attending Brantford Central Collegiate. She graduated in 1877.

Family and Cultural Background

Pauline Johnson’s life was heavily influenced by her mixed-race identity. Her Mohawk name, Tekahionwake (“double wampum”), speaks to this. She was Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and British. Her father was of Mohawk and European descent. Her mother, Emily Susanna Howells, was born in England. She immigrated to the United States with her family as a small child. Originally from Bristol, the Howells were known for their interest in the literary arts. Emily met George while visiting her sister on a mission to Mohawk territory. At the time, George was an interpreter for the Anglican mission. The couple married in 1853. George became chief of the Six Nations soon after. He was also appointed as a Crown interpreter for the Six Nations.

Johnson’s parents’ mixed-raced marriage was initially stigmatized. But Johnson and her family still enjoyed a privileged position in society, mainly because of her father’s social status as a cultural go-between. Her parents hosted notable dignitaries, intellectuals and artists. Johnson lived in an age of institutional racism. But she was taught to appreciate and respect her Mohawk ancestry. She understood Kanyen'kéha, the Mohawk language, and was told many stories by her paternal grandfather, Chief John Smoke Johnson. His dramatic talents inspired Johnson’s work as a poet. She and her siblings inherited some of the family’s traditional Mohawk cultural artifacts when their father passed away in 1884. Johnson used many of these items in her performances, including wampum belts and masks.

Writing and Poetry

Pauline Johnson began writing poetry in her mid-teens. Her upbringing influenced her insights on life, love and the human condition. She was best known for her portrayals of Indigenous culture — particularly women and children. Her talent for the literary arts grew to be multifaceted. She enjoyed great success during her lifetime. She published prolifically in newspapers and magazines in the early years of her career. This makes it difficult to know the entirety of her life’s work. Literary scholars and feminist historians continue to research and write about her.

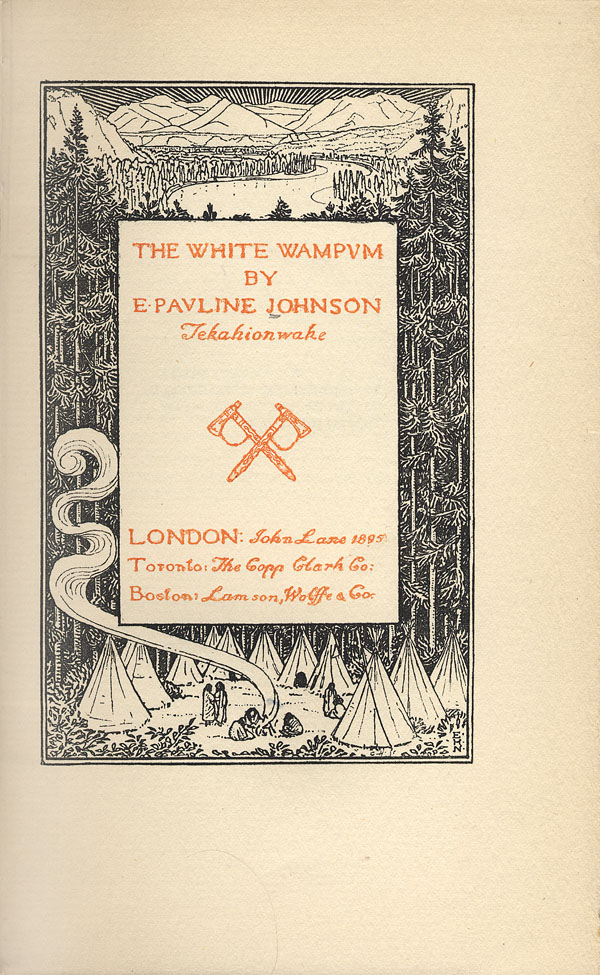

In 1884, Johnson had her work published in the New York magazine Gems of Poetry. She published another three poems in the magazine before 1885, and eight more in the Toronto-based newspaper Week. Johnson soon began to recite her poetry and stories for audiences. She mixed representations of Indigeneity and Anglo-Canadianisms. In 1895, at the height of her success as a performer, she released a collection of poetry, The White Wampum. This was followed by Canadian Born (1903) and Flint and Feather (1912). In 1911, Johnson published Legends of Vancouver, a series of tales and short stories told to her by Joe Capilano, a Squamish chief. Two books of short stories, The Shagganappi and The Moccasin Maker, were published after her death in 1913.

Speaking Tours

Pauline Johnson was in her early 20s when her father died in 1884. She moved to Brantford, Ontario, with her ageing mother and sister and pursued a career in spoken-word performances. In a society with rigid gender roles for women, Johnson and her widowed mother were vulnerable to poverty. Johnson used the money she made publishing and touring to support herself and her family.

Sometime after 1884, Johnson embarked on a series of speaking tours in Canada, the United States and England. These continued until 1909. Her recitations of patriotic poems made her popular among audiences. (See also Patriotic Songs.) After she found success performing her own poetry, she worked Indigenous items in her show. She would start her performance in traditional Mohawk dress, then change into Victorian clothing. This helped to propel her success and notoriety among audiences.

Literary Influences

Much of Pauline Johnson’s writing and performance style reflected early expressions of English Canadian nationalism during an intense period of state formation following Confederation. It has been suggested that Johnson was one of the first Canadian poets to write passionately about camping and living in the wilderness. Some of her poems were included in W.D. Lighthall’s anthology Songs of the Great Dominion (1889). It was one of the first collections to include poetry by both French-Canadian and Indigenous authors. Johnson was also loosely associated with the Confederation Poets in the 1880s. Their literary style linked a love of the natural environment to the essence of being Canadian.

Johnson’s mixed-race parentage and her feminine identity also influenced the tone of her writing and poetry. She lived during an intense period of restrictive legal policies and state regulation of Indigenous peoples by the federal government. (See also: Indian Act; Reserves; Residential Schools.) Her dual allegiances to her heritage represent the complexities of her personal and political experiences. As a racialized and unmarried woman, her position in society was precarious. In some ways, her status as a single and childless woman nurtured the possibility of her professional career in the literary arts. But it also contributed to the poverty she suffered. This was despite her rise as a well-known Canadian poet and performer. It also happened amid calls by the women’s movement to expand respectable roles for women.

Literary Criticism

Some historians have argued that Johnson’s choice to commercialize her Indigenous ancestry helped her to survive the poverty that accompanied her status as a racialized and unmarried woman in White society. Johnson spoke of herself as an Indian, but some critics have challenged this identity. They note that her adult life was spent away from Mohawk culture. She was somewhat removed from Indigenous people. Additionally, her poetry and performances were produced to suit the tastes of White audiences, who were inclined to hold antiquated and racist misconceptions about Indigenous peoples. Her work indicated that she was influenced by an attachment to her Anglo-Canadian roots. Johnson’s performance themes drew heavily on the tropes of the “Indian Princess” and “noble savage,” as they are now recognized by Indigenous peoples, scholars, post-colonial theorists and literary critics.

Johnson often romanticized interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. But she also wrote critically about the stereotypes and circumstances faced by Indigenous peoples during this period. She drew connections between racism, poverty and violence. For example, in “A Red Girl’s Reasoning,” she effectively humanized Indigenous peoples in a climate where mainstream views supported the ignorant claims of scientific racism (see Eugenics in Canada), which created offensive and false categorizations of non-White people in the service of colonization. Johnson was also critical of the impact of Christianity on Indigenous ways of life. She moved diplomatically between distaste for the hard hand of church teachings to a subtler expression of respect for religious authority.

Legacy

Pauline Johnson spent the last years of her life in Vancouver. She died there on 7 March 1913, three days shy of her 53rd birthday. A monument in Stanley Park commemorates her work and legacy. She is also listed as a Person of National Historic Significance in Canada. Her childhood home, Chiefswood, is a National Historic Site and public museum. In 2016, the federal government announced that Johnson was one of 12 iconic Canadian women in consideration to appear on a new banknote. (That honour ultimately went to Viola Desmond. See also Women on Canadian Banknotes.)

Johnson made important contributions to Indigenous and Canadian oral and written culture. She has been celebrated widely since the end of the 20th century. As an unmarried Indigenous woman, and a successful poet and entertainer, Johnson fought against prejudicial ideas of race and gender at the time. Her work was well received by critics and popular audiences during her lifetime. It was largely forgotten in the decades after her death. By the latter half of the 20th century, and with the centennial of her birth in 1961, there was renewed interest in her work. Pauline Johnson continues to be recognized as a talented literary figure.

See also: Vancouver Feature: Pauline Johnson Names Lost Lagoon; The Canadians: Pauline Johnson.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom