Indigenous Peoples to the 1640s

The first people to arrive in the Prairies lived in small groups as nomadic hunters. They arrived in this region of North America at least 13,300 years ago. Discoveries at the Wally’s Beach archeological site in southern Alberta date to this period. The items include hunted horse and camel remains and human-made projectile points.

By about the year 200, people on the Prairies are thought to have lived in small portable tipis. By about the year 600 to 800, they engaged in some agriculture. People on the Plains moved between resource zones according to the season, the fortunes of the hunt and diplomatic relations with neighbouring groups. (See also Indigenous People: Plains.) Different economic adaptations and languages led to the development of distinct Indigenous cultures. There were buffalo-hunting groups on the Plains. Hunting bands combined the harvest of fish and animals in both plains and parklands. Other bands relied on caribou and other resources in the northern forests and tundra. (See also Caribou Hunt.) These groups are represented today by the Cree, Ojibwa, Oji-Cree, Nakoda Oyadebi (Assiniboine), Siksikaitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy) and Dene peoples.

Though it is difficult to estimate, the population on the Prairies was thought to be about 20,000 to 50,000 people by around 1640.

Indigenous People and the Fur Trade: 1650s–1870s

Indigenous people in the western interior experienced significant changes after the arrival of Europeans. (See Plains Indigenous Peoples in Canada.) The most notable included the movement of hunting bands into new territories and the negotiation of new diplomatic arrangements with neighbouring groups. The introduction of infections such as smallpox resulted in epidemics and social disruptions. Smallpox broke out several times on the Prairies, beginning in the mid-18th century. The disease sometimes killed entire bands. (See also Health of Indigenous Peoples.)

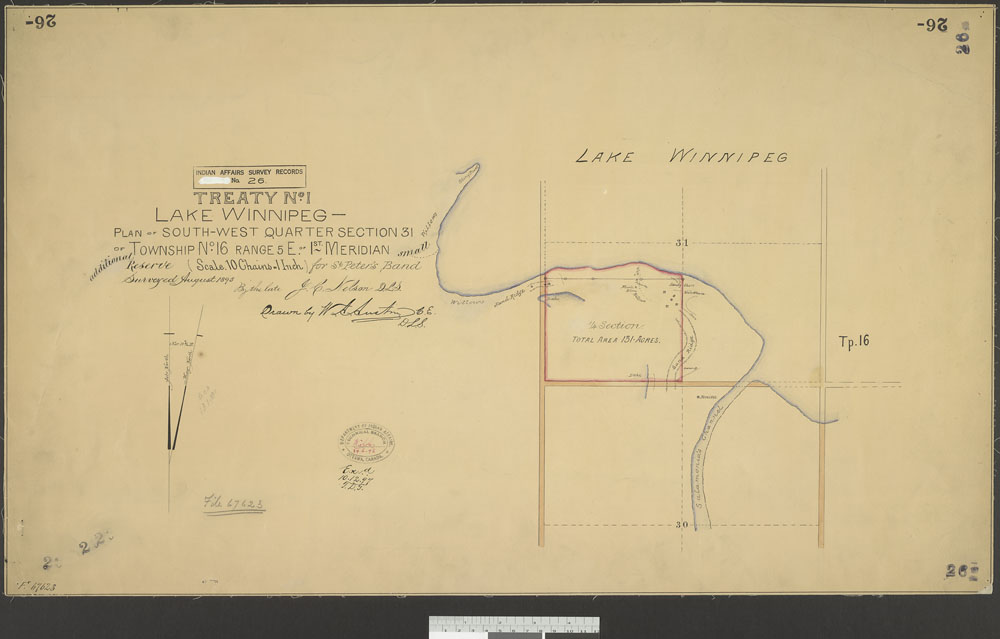

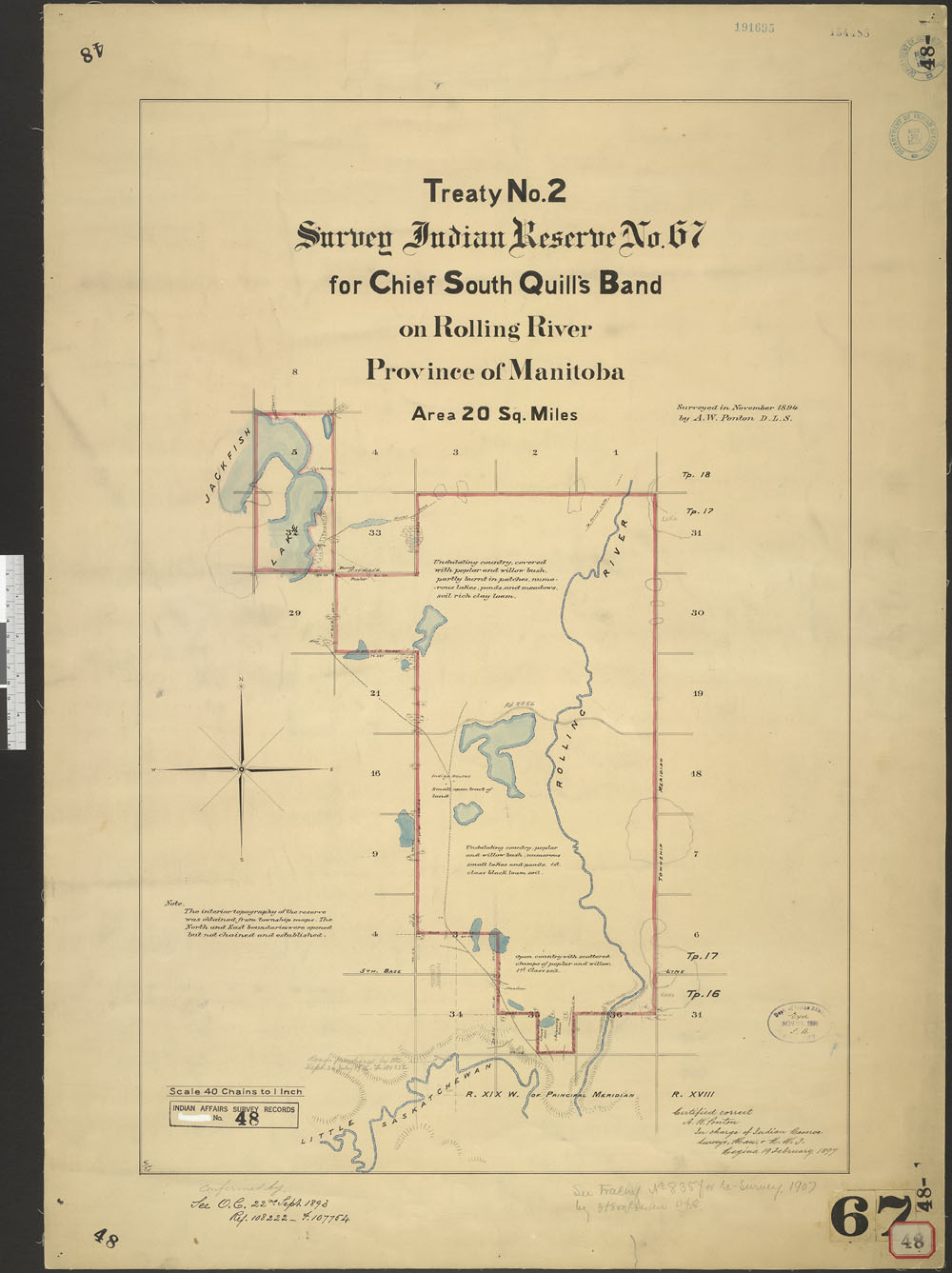

The autonomy of Indigenous peoples was greatly reduced in the 19th century. This was due to increased migration from eastern North America, the expansion of the Canadian nation-state, and the destruction of the most crucial element in the Plains economy: bison. (See Buffalo Hunt.) In the 1870s, seven Indigenous treaties were negotiated between the Canadian government and the First Nations of the western interior. They exchanged sovereignty over the land for government promises of economic assistance, education and the creation of reserves. (See also Numbered Treaties.) Thus, in the space of a few short decades, First Nations on the Prairies became wards of the state.

The European colonization of the western interior began with the fur trade. The English Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), founded in 1670, traded from posts on Hudson Bay. Competition forced it to establish inland trading posts in the 1770s. The French, and later the North West Company (NWC), created extensive networks of posts that were pushed into the Prairies by the La Vérendryes in the 1730s. These networks were extended by Peter Pond in the 1770s and by Alexander Mackenzie from 1789 to 1793. Deadly competition finally forced the merger of the HBC and the NWC in 1821. The restructured HBC ruled the fur trade in the region for another five decades. (See also: Rupert’s Land.)

Red River and Canada: 1840s to 1890

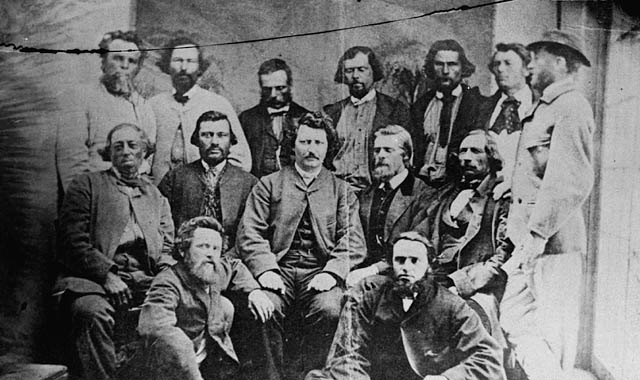

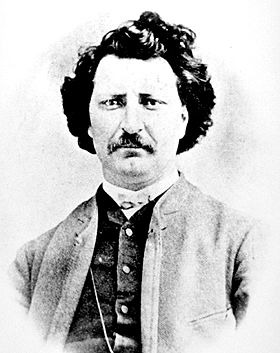

By the 1840s, Métis made up most of the population of the Red River Colony. They were also an important part of fur-trading operations. They defended local interests against incoming speculators when outside pressures increased in the mid-1800s. Canada eventually secured sovereignty over Rupert’s Land, but only after the 1869–70 Red River Resistance. It was led by Louis Riel and resulted in significant changes to the terms that allowed the region to enter Confederation as the province of Manitoba. ( See Manitoba Act.)

The policy framework for developing the western interior was created in Ottawa. This was due to the federal government’s great powers and to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s decision to keep control of western lands under federal jurisdiction. (See also Distribution of Powers.)

Decisions made by the government between 1870 and 1874 remained cornerstones of prairie history for two generations. These policies included homesteading and immigration recruitment, the Dominion Lands Act, and the creation of the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police).

Crucial decisions on tariff policy and the Canadian Pacific Railway followed in 1879–80. The region was to become an agricultural hinterland, built upon immigration and the family farm. It would also be integrated nationally with the growing manufacturing sector in central Canada. (See also Industrialization in Canada.) Other events had an equally significant impact. The failure of the North-West Resistance in 1885 and the passage of the Manitoba Schools Act and anti-French-language legislation in 1890 ensured that the defining elements of prairie society would be Protestant, English-speaking and British. The provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta were created in 1905. (See Autonomy Bills.) By that time, the peaceful evolution from colony to self-governing state seemed to have been fulfilled.

Settlement of the Prairies: 1890s–1930s

New forces were at work in the Prairies around 1900. Social leaders were troubled by the arrival of hundreds of thousands of non-British immigrants. Their influx placed great strains upon prairie institutions during the next few decades. The newcomers, on the other hand, gave up much of their traditional culture as they helped to build the new West.

Scandinavians and Germans assimilated quickly. Mennonites, Jews and Ukrainians sought to retain more of their cultural heritage. They eventually helped create a multicultural definition of Canada. Hutterites remained isolated from the larger community. Other religious groups — notably a few Doukhobors and Mennonites — preferred to leave the region rather than accept its norms. By the 1950s, the Prairies were far closer to a British Canadian model than any other culture.

Political institutions were also severely tested in the early 20th century. A wide gap between the wealthy and the poor produced tensions. Cities such as Winnipeg and Calgary had luxurious homes in segregated residential areas, along with exclusive clubs and colleges. Political and economic power was concentrated in the hands of a small elite who reaped the benefits of economic growth. By contrast, the squalor of slums such as Winnipeg’s North End and Rooster Town, some frontier construction camps, and resource towns such as Lovettville and Cadomin, Alberta, led to the emergence of a workers’ resistance movement. Labour-management conflicts, especially with the Winnipeg General Strike and in Alberta coal-mining towns, should be seen in this context.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom