The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is Canada’s national police force – providing an array of services from municipal policing to national security intelligence gathering. The "Mounties" have a long and proud history dating back to Confederation and the opening of the Canadian West. Despite a series of scandals in recent decades, the RCMP remains one of Canada's most iconic national institutions.

Policing the Frontier

Canada’s national police service had small, temporary beginnings. After Confederation, when the newly formed nation was negotiating the purchase of Rupert's Land, the federal government faced the problem of how to administer this vast territory peacefully. The Hudson's Bay Company had ruled this frontier (what is today northern Quebec and Ontario, all of Manitoba, and parts of Saskatchewan, Alberta and the northern territories) for almost two centuries without serious friction between fur traders and the Indigenous population. There were few traders, and their livelihood depended on economic co-operation with the Indigenous people. The company made no effort to govern the Indigenous population.

The Canadian takeover of Rupert's Land, soon to be called the North-West Territories, meant the imposition of a government that would systematically interfere with Indigenous customs for the first time. Thousands of settlers would arrive to occupy the lands where Cree and Blackfoot hunted buffalo without restraint. At worst, the tensions generated by this process might erupt into the kind of settler-Indigenous warfare experienced in the American West. Apart from the cost in lives on both sides, the Canadian government could not contemplate the expense of a major "Indian war," which might easily bankrupt the country. The government also feared that violence and lawlessness in the new territories might provide American expansionists with an excuse to move in.

Canada in the 1870s, like most jurisdictions whose legal systems were based on English common law, had few police forces. The larger cities had primitive local constabularies; small towns and the countryside had no police at all. In these areas the burden of maintaining public order fell upon the courts, backed up in emergencies by the military.

The British government had some experience with centralized police forces in India and Ireland, however, and the forces there were unquestionably effective. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald therefore adopted the Royal Irish Constabulary as the model for Canada. The police for the North-West Territories were to be a temporary organization. They would maintain order through the difficult early years of settlement, then, having served their purpose, they would disappear.

In 1869 William McDougall, sent out as first Canadian lieutenant-governor of the North-West Territories, carried instructions to organize a police force under Captain D.R. Cameron. Half the men of the force were to be local Métis. However, no such force was ultimately created. The plans had to be shelved when the Red River Resistance of 1869-70 led to the creation of the province of Manitoba in the southern corner of the Territories. Under the British North America Act, law enforcement was a provincial not a federal responsibility.

North-West Mounted Police

Nothing further happened until 1873, when Ottawa, as part of plans to administer the North-West Territories, revived the idea of a federal police force. In May that year, Parliament passed an Act establishing a force, and 150 recruits were sent west that August to spend the winter at Fort Garry (what is now Winnipeg). The following spring another 150 joined them.

The new police force, which gradually acquired the name North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), was organized along the lines of a cavalry regiment and armed with pistols, carbines (small, short-barreled rifles) and a few small artillery pieces. Several reports on the state of affairs in the North-West Territories had stressed the symbolic significance of the traditional British army uniform for the Indigenous people. A scarlet tunic and blue trousers were therefore adopted.

The commanding officer was given the title Commissioner. There was also an assistant commissioner and two officer ranks, superintendent and inspector. Non-commissioned ranks were staff sergeant, sergeant, corporal and constable. The commissioned officers were given judicial powers as justices of the peace. Lieutenant-Colonel George Arthur French, commander of the Permanent Force gunnery school at Kingston, Ontario was the first commissioner.

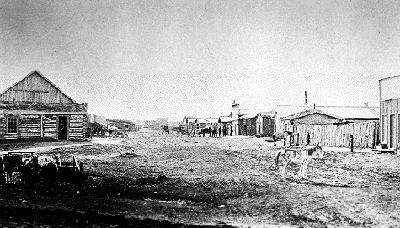

Patrols and Forts Established

On 8 July 1874 the new, 300-man force of mounted police left Dufferin, Manitoba and marched west. Their destination was present-day southern Alberta, where whisky traders from Montana were known to be operating among the Blackfoot people. The previous June there had been a serious incident in the Cypress Hills (in what is now southern Saskatchewan) at a whisky trader's post, in which several Assiniboine were massacred by whites.

After a gruelling march of more than two months the force arrived to find that most of the traders had fled. The Blackfoot almost immediately tested the intentions of the police by reporting the activities of some of the remaining whisky traders. The immediate arrest and conviction of the traders pleased Chief Crowfoot and laid the foundation for good relations with the police. Assistant Commissioner James F. MacLeod, with 150 men, established a permanent post at Fort MacLeod. Part of the remaining half of the force had been sent to Fort Edmonton under Inspector William Jarvis, and the rest under MacLeod returned east to Fort Ellice (near St-Lazare, MB), which had been designated as headquarters.

The following summer, the NWMP established Fort Saskatchewan downstream of Fort Edmonton on the North Saskatchewan River. In 1875 the force also built Fort Calgary on the Bow River, and Fort Walsh in the Cypress Hills. In 1876 another major post was set up at Battleford (in present-day Saskatchewan). The network of police posts and patrols thus began, and was extended year by year until it covered all of the Territories.

Resistance and Modernization

For a decade and a half, the NWMP concentrated on building close relations with Indigenous peoples. The police helped prepare Indigenous people for treaty negotiations with the government, and mediated conflicts with the few settlers in the region. The NWMP played a role in the signing of treaties covering most of the southern Prairies in 1876 and 1877.

The NWMP rarely resorted to armed force before 1885, when the North-West Resistance broke out. Growing unrest in the early 1880s – due to the disappearance of the buffalo, crop failures in the Saskatchewan Valley, and disenchantment with the distant government in Ottawa – led to an increase in the force's strength to 500 men in 1882. But this did not keep pace with the NWMP's growing responsibilities. Construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway had drawn the NWMP into a limited role in southern British Columbia as well as on the Prairies. The police were particularly concerned with the rising unrest in the Saskatchewan Valley and warned Ottawa that violence and trouble was certain unless grievances there were addressed. The warnings were ignored and the resistance took its tragic course. After the Métis and Indigenous forces were defeated, the government increased the NWMP to 1,000 men and appointed a new commissioner, Lawrence Herchmer, to modernize the force.

Herchmer improved training and introduced a more systematic approach to crime prevention, thus preparing the force to cope with the large increase in settlement in the West after 1885. As memories of the resistance faded, criticisms began. In Parliament the Opposition reminded the government that the NWMP had only been a temporary creation, intended to disappear when the threat of frontier unrest passed. The NWMP's demise seemed certain with the election of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier's Liberals in 1896; their election platform had called specifically for the dismantling of the force.

In power, however, the Laurier government quickly discovered intense opposition in the West to their plan. The highly publicized murder of Sergeant C.C. Colebrook by Almighty Voice in 1895, and the manhunt that went on for more than a year, raised renewed fears of a general Indigenous uprising.

Klondike and Arctic Expansion

By the mid-1890s the NWMP had also begun moving north. Rumours of gold discoveries in the Yukon prompted the government to send Inspector Charles Constantine to report on the situation in that remote region. His recommendations led to the stationing of 20 police in the Yukon in 1895. This small group was barely able to cope with the full-scale gold rush that developed when news of large discoveries reached the outside world in 1896. By 1899 there were 250 mounted police stationed in the Yukon. Their presence ensured that the Klondike Gold Rush would be the most orderly in history. Strict enforcement of regulations prevented many deaths due to starvation and exposure by unprepared prospectors.

By 1900 the gold rush was over and the NWMP turned its attention to other parts of the North. In 1903 the first mounted police post north of the Arctic Circle was established at Fort McPherson. Later that year the NWMP began collecting customs duties from whalers at Herschel Island in the Beaufort Sea. At the same time a detachment under Superintendent J.D. Moodie established a post at Cape Fullerton on the western shore of Hudson Bay. The police presence in the Arctic grew steadily from these beginnings, especially after the schooner St. Roch began to be used as a floating detachment, traveling among the Arctic islands in the 1920s.

Royal NWMP

By this time the force was known as the Royal North-West Mounted Police – the "Royal" being added in 1904 in recognition of the service of many mounted policemen in the South African War.

The permanence of the force also became an accepted fact by the early 20th century. When the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were created out of the North-West Territories in 1905, the force was, in effect, rented out to the new provinces. Agreements were signed under which the RNWMP acted as provincial police.

This arrangement worked well until the First World War. The war produced severe shortages of manpower, and created new security and intelligence duties for the police. When Alberta and Saskatchewan decided to adopt Prohibition in 1917, Commissioner A. Bowen Perry believed the new liquor laws were unenforceable, especially amid the new demands of wartime. Perry cancelled the police-service contracts with Alberta and Saskatchewan, which maintained their own provincial police forces for the next decade and a half.

RCMP Established

When the end of war in 1918 reduced the need for security work, the future of the mounted police was very uncertain. Late that year, N.W. Rowell, the president of the Privy Council, a senior federal civil servant, toured western Canada to seek opinion about what to do with the force. In May 1919 he reported to Cabinet that the police could either be absorbed into the army or expanded into a national police force. The government chose the latter course.

In November, legislation was passed allowing the RNWMP to absorb the Dominion Police (a federal force established in 1868 to guard government buildings and to enforce federal statutes). When the legislation took effect on 1 February, 1920, the merged organization was named the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), and headquarters were moved from Regina to Ottawa.

In the 1920s the force's main activities were the enforcement of narcotics laws, as well as security and intelligence work. The latter reflected widespread public fears of political subversion that had been fueled by the Russian Revolution in 1917, and the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. In 1928 Saskatchewan re-negotiated its provincial policing agreement with the RCMP. This arrangement began a return to more normal police duties for the RCMP.

Expansion and War

In August 1931, Major-General James MacBrien became commissioner. The seven years of his leadership marked a period of rapid change. The size of the RCMP nearly doubled in this period, from 1,350 to 2,350 men, as the force took over provincial policing in Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. It also took over the Preventive Service of the National Revenue Department.

Before MacBrien died in office in 1938, he established a policy of sending several members of the force to universities each year for advanced training. He also opened the first forensic laboratory in Regina, and organized an aviation section. In addition, an RCMP Reserve was established in 1937 in the expectation that war was coming and would make heavy demands on the force.

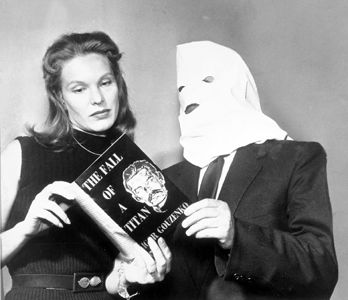

When the Second World War began, the RCMP had comprehensive plans for the protection of strategic installations. Ultimately, no acts of sabotage were recorded during the war. However, Nazi sympathizers were rounded up for internment. Despite having suspicions about Russian espionage, the RCMP was as surprised as most Canadians by the 1945 revelations of Soviet Embassy staffer Igor Gouzenko, who defected with evidence of an extensive Soviet spy network in Canada during the war.

Intelligence Gathering

The international tensions of the Cold War era, which the Gouzenko case heralded in Canada, ensured that security and intelligence work would continue to be a major preoccupation for the mounted police. After Gouzenko, these activities attracted almost no public attention until the mid-1960s, when Vancouver postal clerk George Victor Spencer was discovered to have been collecting information for the Soviet Union. The quiet agreement among politicians that security matters were not subjects of open debate was shattered when John Diefenbaker's Conservative Opposition attacked the Liberal government of Prime Minister Lester Pearson for mishandling the case.

In retaliation, the Liberals revealed details of a scandal involving a German woman named Gerda Munsinger , whose ties to some former Conservative Cabinet ministers – and also to some Russian espionage agents – had apparently been ignored by the previous Diefenbaker government. A Royal Commission on Security was appointed in 1966 as a result of these cases. The commission's 1968 recommendation that a civilian intelligence agency replace the RCMP was rejected by the new Liberal prime minister, Pierre Trudeau.

By 1969, the rise of separatism in Québec had produced a major shift in security and intelligence operations, from a focus on foreign threats to a perceived threat within the country. The October Crisis of 1970 – with the kidnapping of British trade commissioner James Cross and the murder of Québec Cabinet minister Pierre Laporte – greatly motivated RCMP undercover anti-separatist operations in Québec.

The RCMP was subsequently discovered to have engaged in illegal activities in Québec, such as burning a barn and stealing a membership list of the Parti Québécois. These revelations raised fundamental questions about the place of the police in a democratic state. Are there situations in which the police can break the law? Who is ultimately answerable if they do? To help answer these questions the Royal Commission of Inquiry Into Certain Activities of the RCMP was established under Justice David McDonald. The inquiry repeated the earlier recommendation of transferring intelligence operations from the RCMP to a civilian agency. Legislation creating such an agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, was proclaimed on 1 July 1984.

Post-War Policing

The postwar period saw a continued expansion of the RCMP's role as a provincial force. In 1950 the RCMP assumed responsibility for provincial policing in Newfoundland (which had joined Canada in 1949), and also absorbed the British Columbia provincial police.

In 1959, the most serious conflict over the split federal-provincial jurisdiction of the force took place. A loggers' strike in Newfoundland led the commander of the RCMP in that province to ask the provincial attorney general to seek 50 reinforcements from Ottawa. Federal Justice Minister E. Davie Fulton refused, and Commissioner L.H. Nicholson resigned in protest. The question of which level of government controls the RCMP in a given set of circumstances still remains vague. It has been a source of tension between the federal and provincial governments, leading to threats by provinces to cancel their RCMP contracts and establish their own provincial police.

After 1945, three areas of criminal investigation occupied a large and growing portion of the force's time: organized crime, narcotics, and commercial fraud. The first two were closely linked, and from the late 1940s onward there was growing evidence that illegal drug traffic was controlled by Canadian branches of American crime syndicates or "families." In 1961 the RCMP set up national crime intelligence units across the country to gather information on organized crime and improve co-operation with other police forces. Similarly, growing numbers of securities frauds and phony bankruptcies led the RCMP to establish commercial fraud sections, with specially trained personnel, beginning in 1966.

Training

Since 1886 all basic training of RCMP recruits has been carried out at Depot Division in Regina. Today the course for new cadets is six months in length, is offered in both official languages, and includes a variety of subjects from basic criminal law to driving and shooting, fitness, and police tactics. Depot Division also gives courses for fisheries enforcement officers, correctional services personnel, native special constables and tribal police, other regulatory and law enforcement agencies. Depot Division also operates a Police Dog Service Training Centre in Innisfail, AB.

Since 1974, women have been recruited into the force and undergo the same training as male constables. Upon graduation, female constables are assigned duties on the same basis as their male counterparts.

Musical Ride and the Mountie Brand

From its earliest years, the mounted police force has attracted the attention of writers. Hundreds of novels, stories and films, mostly by British and American authors, have appeared over the last century, creating a vivid popular image of the Mounties as fearless and infallible. The Canadian government realized the usefulness of this image as early as the 1880s. The scarlet-coated policeman began to appear on Canadian immigration pamphlets and shortly after that on tourist advertisements.

The force itself has always recognized the value of good public relations. Early riding drills developed quickly into public exhibitions of horsemanship set to music. The origins of the famous musical ride can be traced back to the 1870s. Although mounted training once required of all recruits has long since disappeared, the musical ride remains an enormously popular public attraction in Canada and elsewhere. The symbolic importance of the Mounties as icons of Canadian identity, may explain why they have retained their popularity – if not their prestige – amid harmful publicity in recent decades.

Sexism, Religious Accommodation and Equality

By the 1970s, the RCMP was making increased efforts to break entrenched attitudes left over from its origins as a white, all-male paramilitary organization. That process began in earnest in 1975 after the graduation of the first all-female troop of officers from the RCMP training depot. It accelerated further after the 1982 adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Canadian Constitution, which bolstered demands within the RCMP for gender equality, including an increase in the number of women in the force. This led to major challenges for an institution that in many ways remained an “old boys club,” dominated by influential older officers who had joined in the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1987, the RCMP also began affirmative action policies aimed at recruiting visible minorities. The following year – in response to an application to join the force from Baltej Dhillon, a Sikh man – the commissioner recommended removing the force's ban on beards and turbans. The issue sparked controversy across Canada. However, in 1990, the government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney announced several changes to the RCMP dress code, including the introduction of trousers for female officers, and the freedom to wear beards and turbans for Sikhs. Dhillon would become the first Mountie to wear a turban as part of his uniform.

Progress was particularly slow in the area of sexual harassment. The 2013 release of No One to Tell: Breaking My Silence on Life in the RCMP – a book by Janet Merlo, an ex-officer, which alleged sexual harassment and gender discrimination during the author's 19 years of service in the force – provided a telling example. The book spurred calls for a class action lawsuit by hundreds of current and former female officers, who put forth a litany of complaints. These included unwanted sexual touching, harassment, threats and even rape.

Particularly damning were claims made to the CBC by dozens of female officers who alleged that they were punished for complaining about such treatment. Among those who went public about a culture of harassment and bullying inside the force was Corporal Catherine Galliford. Until her allegations surfaced in 2011, Galliford had been the public spokeswoman for the RCMP on several high profile cases in British Columbia, including the investigation into the Air India bombing. Galliford sued the RCMP, eventually settling her lawsuit out-of-court after a four-year legal battle.

An internal RCMP report made public in 2012 said female members of the force suffered frequent harassment. In 2013, Commissioner Bob Paulson announced an action plan to respond to harassment complaints. Two years later, Paulson said the RCMP had "moved beyond" its sexual harassment problem. In 2013 the force also announced plans to boost the number of female recruits so that women would make up half of the cadets at its Regina training camp. As of 2014, women represented 21 per cent of RCMP officers on the force overall. The RCMP's stated goal was to increase that number to 30 per cent by 2025.

Maher Arar

In the early 1990s, the RCMP gave up responsibility for the Special Emergency Response Team (SERT), a special forces unit mainly responsible for anti-terrorism operations, including overseas. Foreign anti-terrorism operations were transferred to the Department of National Defence, leaving the RCMP to focus on domestic terrorist criminal activity. To counter that threat, the force maintains relationships with a variety of other domestic and international agencies, including United States government agencies.

Among the information the RCMP shared with the US government in the wake of the 11 September 2001 terror attacks was the allegation that Maher Arar, a Canadian citizen, was an Islamic extremist with possible links to the Al Qaeda terrorist group that carried out the attacks. As a result, Arar, an Ottawa telecommunications engineer, was arrested during a vacation stopover in New York City in 2002 and sent to Syria, where he was imprisoned for 10 months and tortured.

Arar was returned to his family in Canada in 2003, insisting upon his innocence. His case prompted a commission of inquiry, which cleared Arar of any involvement in terrorism and blamed the RCMP for sharing faulty intelligence reports about Canadians with authorities in another country. Arar received a public apology from Prime Minister Stephen Harper and $10.5 million in compensation from Ottawa.

The RCMP's role in the Arar scandal undermined its public image, and led to the resignation of RCMP Commissioner Giuliano Zaccardelli, after revelations that Zaccardelli had mislead Parliament about the force's role in Arar's arrest and transfer to Syria.

Scandal, Mismanagement, Cover-up

The Arar affair was only the beginning of a steady diet of bad news surrounding the RCMP that tarnished the force's once-proud image through much of the 2000s. This included accusations of failure in the investigation of the 1985 Air India bombing; revelations that the RCMP's pension fund was plagued by financial abuse; evidence of manpower shortages and poor training for young officers sent to remote communities – following the shooting deaths of two Mounties on northern assignments; and evidence of an internal culture of persecuting whistle-blowers who attempted to bring such problems to light.

Perhaps most damaging to the RCMP's reputation was the scandal surrounding Polish immigrant Robert Dziekanski, who died after being repeatedly shocked with Taser guns fired by a group of Mounties at Vancouver airport in 2007. An inquiry into the death revealed that the RCMP tried to cover up embarrassing details about the incident, and deliberately fed false information to the news media reporting on the matter.

Only months before Dziekanski died, William Elliott, a federal bureaucrat, had been appointed the RCMP's first civilian commissioner, tasked with cleaning up the force's incompetence and restoring its integrity. It proved to be a tall order. Many of the institution's problems – particularly its lack of transparency and accountability to Parliament – still remained in 2011 when the experiment of a civilian leader ended, and Elliott was replaced as commissioner by Bob Paulson, a career Mountie.

Commitments, Risk, Change

In spite of its troubled recent history, today the RCMP maintains vast and varying commitments, as a national, provincial and municipal policing body. As of 2015, the RCMP’s 28,400 employees were focused on five overarching priorities: combatting serious and organized crime, helping youth, supporting Indigenous communities, countering commercial and economic crime, and safeguarding national security.

The RCMP’s formal primary mandate still remains the prevention of crime and the maintenance of "peace and order." It also provides police services to eight of the ten Canadian provinces, (excluding Québec and Ontario), as well as to the three northern territories, and more than 180 municipalities and Indigenous communities. In recent years its leaders have warned that the RCMP is stretched thin – that its work is carried out with increasingly limited financial and human resources.

This work is as dangerous, or more so, than when the first North-West Mounted Police patrolled the frontier West. In 2005, four Mounties were shot and killed by James Roszko while they were patrolling his property in Mayerthorpe, Alberta. In 2014, three other officers were killed by a gunman wandering through a suburb of Moncton, New Brunswick.

Amid more than a century of tradition, the RCMP also faces ongoing change. Following a ruling from the Supreme Court of Canada, legislation was introduced in Parliament in 2016 to change the Public Service Labour Relations Act, allowing Mounties to form a union. For the first time in their history, RCMP members will have the ability to bargain collectively for employment contracts and conditions.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom