Name Origin

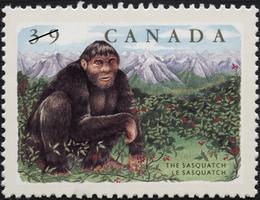

The word Sasquatch is believed to be an Anglicization of the Salish word Sasq’ets, meaning “wild man” or “hairy man.” J.W. Burns coined the term in the 1930s. Burns was an Indian agent assigned to the Chehalis Band, now known as the Sts’ailes First Nation. The Sts’ailes people claim a close bond with Sas’qets, and believe it has the ability to move between the physical and spiritual realm. Sasquatch has also been commonly known as Bigfoot in the Pacific Northwest of the United States.

In this episode of The Secret Life of Canada, Leah and Falen explore the truth behind two very old stories. Sasquatch and Ogopogo are legendary creatures of land and sea — but how exactly did they go from sacred figures in Indigenous oral histories to terrifying beasts and dopey-looking mascots?

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Sightings

Sasquatch is often described as bipedal, measuring up to 2.75 m in height and 360 kg in weight, and covered in long dark hair. Its footprints are said to measure up to 50 cm. Plaster casts of what are said to be Sasquatch tracks are often offered as proof of its existence, though the authenticity of such tracks is highly disputed. Film footage shot in 1967 that purports to show Bigfoot running through the woods near Bluff Creek, California, is perhaps the most famous evidence offered of the cryptid by its proponents. There has been no documented discovery of Sasquatch remains.

An 1884 article in Victoria’s British Colonist is often cited as the earliest documented evidence of a Sasquatch sighting. The article describes the capture of a “half man and half beast” near Yale, BC. Nicknamed “Jacko,” it was described as “something of a gorilla type” that resembled a human covered in thick, glossy black hair. The creature was said to be found unconscious on a set of railway tracks, and upon awakening, chased by a group of men to a set of bluffs above the town. The men reported corralling “Jacko” on a rock shelf and dropping a rock on its head, knocking him out. Two days later, the newspaper ran a letter to the editor from J.B. Good, former superintendent of the Lytton Indian Mission. Good wrote that he had heard similar stories of “wild men of the woods” spotted by groups out hunting or fishing. Though he had initially dismissed their stories, on hearing of Jacko’s capture, Good wrote: “truth is stranger than fiction, and facts are stubborn things.”

In his research, John Green, a BC-based author of many books on Sasquatch, found contemporary newspapers decrying the story as a hoax. Green compiled a database of 1,340 Sasquatch or Bigfoot sightings in North America between the early 19th century and 1995. According to Green’s analysis of witness accounts, Sasquatch is said to possess superhuman speed, step length and strength, as well as the ability to overcome extreme obstacles by striding through heavy brush, ascending steep banks and hurdling high objects. Some report that Sasquatch is also able to swim.

In summer 2011, a British Columbia man shot a video purporting to show a possible Sasquatch in the Tantalus mountain range near Squamish, and later posted the video to YouTube. The unidentified figure can be seen moving swiftly up the slope of a snow covered mountain.

Sasquatch Seekers

J.W. Burns was the first to write about Sasquatch, collecting tales of Sasq’ets sightings from community members for a story in Maclean’s magazine in 1929. The article was published on April Fool’s Day, leading many to dismiss it as a prank. While the legend of Sasquatch persisted, it faded from public consciousness over the following decades.

Sasquatch re-emerged in the 1950s, when two men began to separately investigate the legend. René Dahinden was perhaps Canada’s best-known Sasquatch researcher. Dahinden immigrated to Canada from Switzerland in 1953; and after hearing of Sasquatch shortly after his arrival, moved to BC. Dahinden collected hundreds of Sasquatch footprint casts and interviewed hundreds of witnesses along the West Coast of North America. Though Dahinden, who died in 2001, dedicated his life to finding Sasquatch, he once told a close friend: “I’ve spent over 40 years — and I didn’t find it. I guess that's got to say something.” John Green was a journalist and newspaper publisher in the 1950s when he started to research and write about Sasquatch. He is considered to be the foremost living expert on Sasquatch.

Sasquatch activity, through sightings and research, has been concentrated in Canada in the region surrounding British Columbia’s Harrison Lake. The area has embraced this association. The town of Harrison Hot Springs held its first Sasquatch Days in 1938. It was a two-day event attended by Indigenous peoples from Canada and the United States. Sasquatch Days were re-launched as an annual celebration in 2012. A provincial park on the eastern edge of Harrison Lake was renamed Sasquatch Provincial Park in 1968. The Sts’ailes Band’s logo is a Sasquatch designed by artist Ron Austin.

Academic Research

In 2012, researchers from Oxford University and the Lausanne Museum of Zoology launched the Oxford-Lausanne Collateral Hominid Project to explore the genetic relationship between Homo sapiens and other hominids. Led by Professor Bryan Sykes, researchers put out a call for submissions of organic material suspected to have come from cryptids like Yeti, Bigfoot and Sasquatch. The team analyzed 36 samples — mostly hair — from several countries, including the United States, but not Canada. Most were found to be from bears and other common animals like horses, porcupines and sheep. One was human. However, Professor Sykes told media that while these samples turned out not to be from the ape-like creature, it “doesn’t mean the next one won’t.”

In 2017, a team led by geneticist Charlotte Lindqvist of the University at Buffalo determined that eight hair samples purportedly from Yeti in fact belonged to bear species of the Himalayan region. A ninth sample, a tooth, was found to be a dog’s.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom