First Store: 1869

Timothy Eaton came to Canada from County Antrim (now in Northern Ireland) in 1854. He was part of the large wave of Irish migration during the 1840s and 1850s, and joined his eldest brother and sisters in Upper Canada. With his brother James, he entered into the dry goods and retail business, first in Kirkton, then St. Mary’s, Ontario. Eventually, Timothy and James began quarrelling over their business practices, and Timothy left for Toronto.

In Toronto, Timothy and wife Margaret paid $6,500 for a dry goods retail operation. In December 1869, they opened a store that accepted cash only, at a fixed price, breaking with expectations of bargaining and credit sales. While not the first to do this in Canada, it was a bold decision for a new business. To attract customers, Eaton emphasised both quality and low prices, and also placed well-priced items in front of the store or just inside the doorway. He also developed a novel “Goods Satisfactory or Money Refunded” policy in 1870 — if the customer wasn’t happy, he would refund their money. Eaton also distinguished himself from competition by seeking to cut out wholesalers as much as possible. Most retailers relied on wholesalers who brought goods from manufacturers; Eaton went to the United Kingdom and Europe himself and bought directly from suppliers.

Early Eaton's Locations, Toronto

During the 1880s, Eaton’s store enjoyed strong revenues and expanded. In 1882, he acquired a prime location along Yonge Street, and opened new retail space, with four floors of selling capacity, elevators, and electric lights. Not long after the opening of the new Yonge Street store, Eaton began acquiring rights to surrounding properties, with an eye on further expansion. By the late 1880s, the company’s deep roots in Toronto, and its foundations for national expansion, had been established.

Eaton’s Catalogue: 1884 – 1976

The expansion in Toronto was fuelled in part by the strong demand for Eaton’s low-priced and attractively displayed goods, which found patronage among Toronto’s middle classes. Further driving demand was the creation of a successful catalogue business. The first catalogue was issued in 1884 during the Toronto Industrial Exhibition as a way for the company to advertise its wares to attendees from outside Toronto. The catalogue was successful and orders began to come in from throughout Canada. As the railway system grew, Eaton’s was able to offer lower freight rates to customers, eventually leading to free freight for orders over $25. By 1903, the company opened a mail order building in Toronto to accommodate the trade. While catalogue business eventually came to a close in 1976, throughout the early 20th century it helped fuel the company’s expansion.

Winnipeg Store: 1905

Eaton’s established its first major presence outside Toronto on Portage Avenue in Winnipeg , in 1905. The five-storey store, headed by Timothy’s son John Craig Eaton, made a stir with its elaborate lighting, sprinkler systems, and escalators that had not been seen in the city before. The Winnipeg store also gave the catalogue business a base to further expand its western presence. Winnipeg was the last major expansion overseen by Timothy Eaton, who died suddenly of pneumonia in 1907, and John Craig took over as company president. Eaton’s expanded under John Craig’s watch, with new mail order and distribution centres reaching Saskatoon and Regina, Saskatchewan and Moncton, New Brunswick between 1916 and 1920.

Expansion

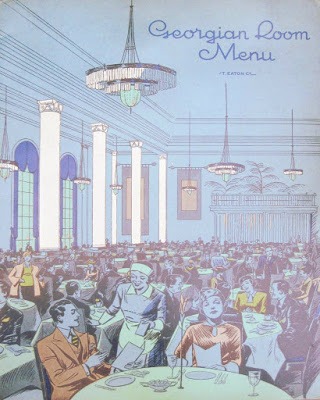

Eaton’s grew at a rapid pace during the 1920s as consumer demand grew. Timothy Eaton’s nephew, Robert Young (R.Y.) Eaton, took over the firm after John Craig’s death, from influenza, in 1922. The expansion included purchasing the Montréal retail firm Goodwin’s Limited. Through the decade, department stores were opened in Red Deer, Lethbridge, Medicine Hat, Edmonton and Calgary, Alberta; Saskatoon and Prince Albert, Saskatchewan; Hamilton and Port Arthur, Ontario; and Halifax, Nova Scotia. The company further grew after purchasing a small chain of retail stores, Canadian Department Stores, giving the company a presence throughout Ontario, including Chatham, Belleville, and Huntsville. In 1930, the company’s Toronto presence further expanded with the opening of a new location at Yonge and College. The location sought to impress Eaton’s position as a determiner of good taste in Canada, featuring marble-faced elevators, an auditorium, and a posh restaurant, the Round Room. The restaurant was particularly inspired by Lady Florence Eaton, a company director, who sought to bring the opulence enjoyed by London shoppers to Toronto. Prior to the Round Room, her efforts in this regard included the opening of the Georgian Room in 1924 in a renovated section of the store at Yonge and Queen. By 1930, the company employed just over 25,000 people, and controlled almost 60 per cent of department store sales in Canada. At no other point would the company dominate the Canadian retail landscape to the same degree.

Labour Issues

While the company grew, it had a mixed relationship with workers. On the one hand, the firm prided itself on providing employees with reasonable work hours. Stores had a strong policy of closing early, and its factory workers typically worked shifts of 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. In addition, Eaton’s employees could access a range of medical services, social programs and clubs. On the other hand, the company resisted unionization, starting with the use of strikebreakers (workers employed in place of those on strike) to defeat a strike by cloak makers in 1899. Women also fought against wage gaps between themselves and male employees. For example, during the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, 485 women joined the strike. While some were re-hired afterward, hundreds of others lost their jobs due to their participation.

During the Depression, criticism of the company sharpened. The opulence of the stores and the handsome returns enjoyed by the Eaton family contrasted with growing economic hardship. Under the populist Henry Herbert Stevens, the Royal Commission on Price Spreads, which looked at the effect of mass purchasing by department stores on smaller retailers, examined the company for several alleged practices. Among the activities that the commission uncovered was Eaton’s powerful purchasing position, which put pressure on manufacturers to provide Eaton’s with low-cost goods and undercut smaller retail competitors. Further, the detailed public examination of Eaton’s books revealed that while the company was cutting jobs and wages, directors were collectively making millions in wages, bonuses and pensions. The public criticism had a long-term impact on company president R.Y. Eaton, who became critical of departments that reported profits above two per cent while he led the company though the 1930s and 1940s.

Nationalism

Eaton’s, founded by a Northern Irish immigrant, was closely tied to the idea of Canada as part of the British world and empire. The firm celebrated the links between Eaton’s, the railroad, and Canadian industrial and economic development. For instance, advertisements cast the company’s expansion into Winnipeg as a major moment not just for the company, but also for Canadian western expansion. The company took pains to emphasize the links between Canadian and British identity and colonialism. Company stores marked coronations and royal visits to Canada with lavish decorations, Union Jacks and other icons of Britain; this was done for the visit of the future King Edward VII in 1901, the coronation of King George VI in 1937, as well as King George’s subsequent visit in 1939. During the First World War, John Craig’s efforts to provide and promote contributions to the war effort led to his knighting in 1915.

Santa Claus Parade: 1905 – 1981

In 1905, Eaton’s launched its famous Santa Claus parade. The first parades, in both Toronto and Winnipeg, were relatively simple affairs, with Santa journeying from the train station to the Eaton’s locations on Yonge and Portage streets respectively. Over the next decade, the event became more complex, with more floats and characters participating along longer routes. The parades expanded along with the company, eventually being held throughout Canada as Eaton’s expanded into Montréal, Edmonton and elsewhere. They incorporated a wide range of fantastic — and racist — characters, from popular figures of children stories from Mother Goose to assemblages of people in blackface or Indigenous caricature. For some time, the parades signalled the beginning of the Christmas shopping season in many cities. The event would set off a fury of construction, costuming and planning in cities throughout Canada, but as the Toronto parade came to be televised, others were halted. By 1967, even the Winnipeg event had been cancelled in deference to the nationally broadcast Toronto version, and by 1969 Toronto’s was the only Eaton’s parade. The final Eaton’s parade was held in 1981.

Postwar Years

A quickly growing middle class offered substantial retail opportunity in the postwar period. The company picked up after depression and war, launching an ambitious program of expansion. In 1948, the company, now headed by John Craig’s son, John David Eaton, purchased the large British Columbia department chain, David Spencer Limited; this immediately gave the company a strong foothold in the province. The purchase was not without difficulties, as the sudden change in ownership left the stores poorly prepared for the busy Christmas season, and the company languished behind the Hudson’s Bay Company in the province. However, by 1957, Eaton’s had a department store in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island and Gander, Newfoundland, giving the company the distinction of having a department store in every Canadian province.

However, the postwar period was not entirely smooth sailing. In 1948, the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) sought to unionize the 12,000 Toronto employees, launching a four-year struggle with the company. The campaign was limited by several factors, including the CCL’s emphasis on male claims to wages that could support them and a family, despite the large number of women involved in the effort. Further, the Eaton’s family resisted the campaign, through actions against the union and by extending company benefits, including expanding a shared contributory pension scheme. After a lengthy battle, the Eaton’s employees voted against joining the union.

Competition from Simpsons-Sears

In 1952, the U.S. department chain Sears Roebuck reached an agreement with the Canadian department chain Simpsons to create a new joint venture, Simpsons-Sears Ltd. Simpsons had five retail locations and a relatively strong mail order business. Simpsons’ Canadian presence, combined with Sears’ significantly larger pools of capital and its network of manufacturing links, offered a strong challenge to Eaton’s. Appealing to nationalism, Eaton’s briefly rebranded its stores as “Eaton’s of Canada.” Meanwhile, Simpsons-Sears expanded aggressively in Canadian suburbs, offering ample parking to the car-driving consumer. Eaton’s locations in car-unfriendly downtowns increasingly limited growth. Simpsons-Sears also used credit terms that enabled buy-now pay-later sales on installment. Stretching back to the days of Timothy Eaton, Eaton’s resisted credit sales, preferring to offer deposit accounts whereby customers deposited money with Eaton’s (with interest), that they could use for purchases at the stores. Customers increasingly preferred Simpsons-Sears’ terms.

As Simpsons-Sears grew, Eaton’s faced a number of internal challenges. John David Eaton struggled in his role as president, lacking the flexibility to respond to new market changes. He relied on a team of store managers and executives who lived lavish private lives and tended to make limited efforts to refresh their store layouts. In 1965, Eaton’s sold off its struggling Canadian Department Stores branches, and suffered from the fallout of a disastrous computer customer account system that ended with over 100,000 customers cancelling their accounts after constant accounting errors. In 1972, the company attempted an ambitious new branch of discount stores, Horizon, but were compelled to either fold them back into the main brand or close them after only a few years. After continuing to struggle with Sears’ aggressive competition in the catalogue business, Eaton’s halted their iconic catalogue services in 1976, cutting over 9,000 jobs. By 1978, Eaton’s was behind both Sears and Hudson’s Bay in Canadian retail sales, a considerable drop from their initial postwar position.

Eaton’s Centre

The creation of the Eaton’s Centre in downtown Toronto was one notable achievement during the postwar period, but it came only after a long struggle. The centre, which continues to bear the name of the defunct firm, opened in 1977, replacing the company locations at College and Yonge Street and at Queen Street. The Centre was a product of compromise, as an initial company plan from the 1960s sought to demolish Toronto’s Old City Hall, located just west of the Queen Street location. That scheme met with considerable public resistance and was abandoned. After further protracted negotiations, plans to create the Eaton’s Centre were agreed to by company and city, and construction began in the summer of 1974.

Bankruptcy

When Eaton’s cancelled their participation in the Toronto Santa Claus parade for 1982, their role in the Canadian retail and cultural landscape shrank further still. A series of marketing missteps, including the cancellation of the popular Trans-Canada sale, created further ill will towards the company. The firm continued to struggle with overcapacity, as the massive downtown Eaton’s stores did not make sufficient sales to justify their size. In 1997, after years of losses, George Eaton was compelled to announce that the company could not meet obligations on its debts to banks and suppliers, totalling over $300 million, and the company sought protection under the federal Companies Creditors’ Arrangement Act. Two years of cutting and restructuring could not save the firm, and it declared bankruptcy in August 1999. Sears Canada took over the company shares, turning the remaining Eaton’s stores into Sears stores. It was an ignoble end to a company that had done much to shape the Canadian economy and shopping for much of the 20th century.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom