The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz is Mordecai Richler’s fourth and best-known novel. Published in 1959, it tells the story of a young Jewish man from Montreal who is obsessed with acquiring status, money and land. Bitingly satirical, it is a landmark Canadian novel. It established Richler as an international literary figure and sparked an interest in Canadian literature both at home and abroad. It also drew criticism from those who felt the main character embodied anti-Semitic stereotypes. Richler also received several awards and an Oscar nomination for his screenplay for the 1974 feature film adaptation, co-written with Lionel Chetwynd and directed by Ted Kotcheff.

Background

Mordecai Richler was born 27 January 1931 in Montreal. He was the grandson of a rabbi and grew up on St. Urbain Street in the working-class Jewish neighbourhood of Mile End. The neighbourhood forms the setting of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. The title character was born around roughly the same time as Richler.

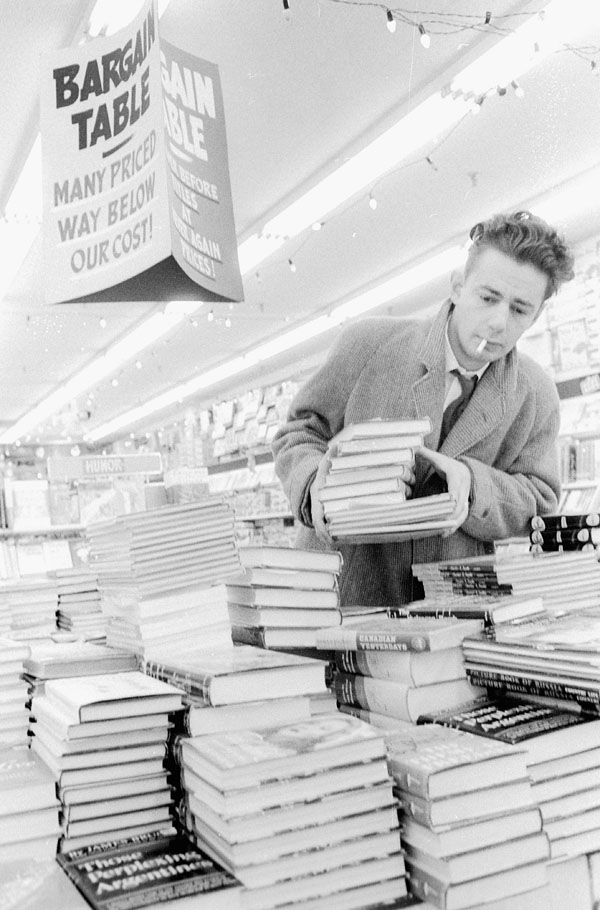

Inspired by Lost Generation writers, Richler moved to Paris when he was 19. He completed his first book there, The Acrobats, which was published in 1954. After a brief return to Montreal, where he worked for the CBC, Richler moved to London, England, where he lived for 20 years and published seven novels. The first two set the stage for The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. Son of a Smaller Hero (1955) was based in the Montreal neighbourhood where he grew up but dealt with it in a more gritty and realistic manner. A Choice of Enemies (1957) is set among a group of writers and filmmakers who fled McCarthyite America to live in London. It adopted a more satirical tone, which would carry over into Duddy Kravitz.

Plot Synopsis

The novel begins in 1947. Duddy Kravitz is a poor,anglophone Jewish student attending high school on St. Urbain Street in Montreal. Though he has grand ambitions, Duddy is generally looked down upon or dismissed by most people in his life, particularly his extended family, who prefer his brother Lennie, an aspiring doctor. The lone exception is Duddy’s grandfather, Simcha, who appreciates Duddy’s striving qualities. Simcha gives Duddy a piece of advice: “A man without land is nobody.” Duddy takes this to heart and makes it his goal in life to acquire land for himself and his grandfather.

Upon graduating, Duddy begins working at a resort in the Laurentian Mountains. He meets and eventually begins dating Yvette, who introduces him to a secluded lake near the resort. Duddy decides to buy up the land surrounding the lake and turn it into a hotel and children’s camp. Duddy returns to Montreal to make money any way he can. His first scheme involves making bar mitzvah and wedding films with a blacklisted British filmmaker, Peter John Friar. Duddy later attempts to connect with the “Boy Wonder” — Jerry Dingleman, a local St. Urbain legend who has made it big.

While unknowingly smuggling heroin for the Boy Wonder, Duddy meets Virgil, an epileptic American who becomes Duddy’s best friend. After Friar abandons Duddy, he and Virgil begin a business distributing films, with Virgil acting as a travelling projectionist. Duddy begins making enough money to start buying up the land in the Laurentians, but his ceaseless ambition begins to affect his friendships. While driving, Virgil suffers an epileptic fit and is paralyzed in a crash. Yvette blames Duddy, who pushed Virgil to drive despite his condition. Yvette leaves Duddy to care for Virgil.

After a nervous breakdown causes him to lose all his clients and declare bankruptcy, Duddy tries to reconcile with Yvette and Virgil. He does this partially because all the land he owns is technically in Yvette’s name, as Duddy was a minor when he started buying it. When the last plot of land comes up for sale, Duddy does not have enough money to buy it. Rather than give up on his dream, though, he forges Virgil’s name to a cheque. Yvette finds out and is outraged. She tells Duddy’s grandfather, who is disgusted at his greed (it is implied that he intended his advice as a Zionist sentiment, and not as a literal suggestion).

Duddy is left with no friends, supporters or money. When he goes to visit his father in a St. Urbain bar, though, he is given a bar credit, because the waiter recognizes him as the owner of the land in the Laurentians. The novel ends with Duddy celebrating, as he feels this officially marks him as someone who has made it.

Criticism

Duddy’s relentless ambition and Jewishness led some to dismiss the book as anti-Semitic. They claimed Duddy embodied the worst stereotypes of Jewish people. This criticism is somewhat blunted by Richler’s self-awareness, as well as his strong, if sardonic, connection to his Jewish roots. (“To be a Jew and a Canadian,” he once wrote, “is to emerge from the ghetto twice, for self-conscious Canadians, like some touchy Jews, tend to contemplate the world through a wrong-ended telescope”.) Within the book itself, for instance, Duddy’s uncle Benjy refers to Duddy as a “pusherke, a little jew-boy on the make,” while a non-Jewish character remarks that “It’s the cretinous little money-grabbers like Kravitz that cause anti-Semitism.”

Reception and Legacy

Though initial sales of the book were low, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz received much praise in the United States and the United Kingdom. Richler became a notable literary figure across the English-speaking world after its publication.

In a 1959 review, the New York Times praised the book as “brash and blatant as a sports car rally — and as suggestive of power.” A reviewer with Canadian Literature praised Richler for his humour, social critique and ability to turn “the vernacular into a poetry, making Duddy memorable, without departing from the dirt, the sadness and the spikes.” The novel is one of Richler’s best-selling books, and arguably the one that most closely embodies his wish to “be an honest witness to my time, my place, and to write at least one novel that will last, that will make me remembered after death.”

Duddy Kravitz became something of a signature character for Richler; he also makes brief appearances in Richler’s later novels St. Urbain’s Horseman (1971) and Barney’s Version (1997).

Film Adaptation

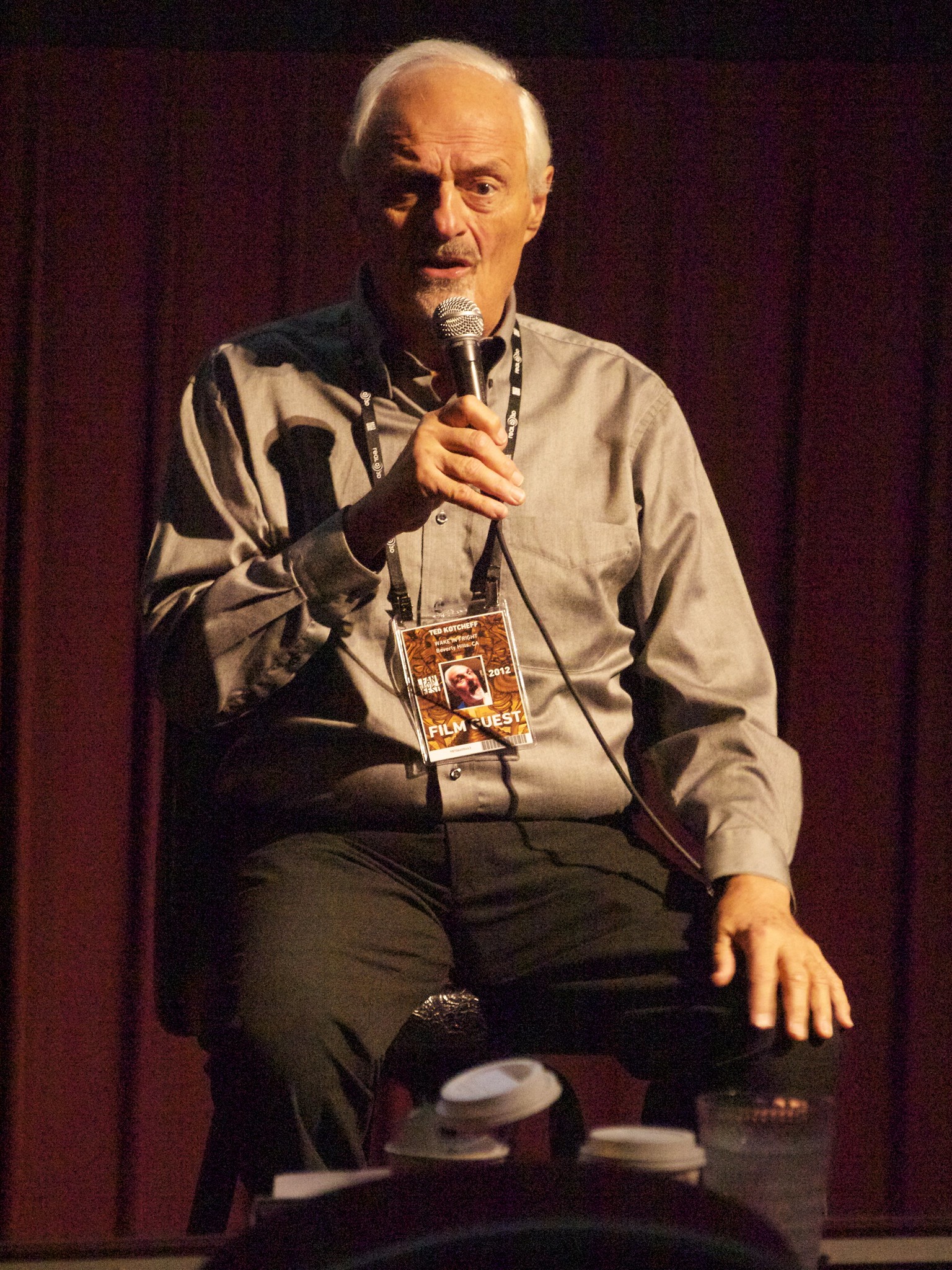

Director Ted Kotcheff and Mordecai Richler met in Paris in the late 1950s and became lifelong friends. While sharing an apartment in London in 1958, Kotcheff read the manuscript for Richler’s novel. He liked it so much that he swore to one day return to Canada and make it into a film. Financing was initially hard to come by, as many producers were afraid of meeting the same charges of anti-Semitism that were levied against the book.

The project finally moved forward after veteran National Film Board (NFB) producer John Kemeny helped secure funding from the Canadian Film Development Corporation (now Telefilm Canada). Richler spent six weeks polishing the screenplay, which he co-wrote with Lionel Chetwynd. Richard Dreyfuss was cast late in pre-production when Kotcheff’s casting agent friend, Lynn Stalmaster, recommended a young actor “who was born to play this part.” The film was shot primarily in Montreal on a budget of $900,000.

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz occupies an unusual place in Canadian film history. Undeniably successful, it won the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin International Film Festival prior to its release in April 1974 and was named Film of the Year at the Canadian Film Awards. It was also the most commercially successful Canadian film to that time; the first Canadian film to gross more than $1 million domestically, and the first Canadian feature film to earn an Oscar nomination (for Richler and Chetwynd’s adapted screenplay). But it was also shunned by many Canadian critics for the compromised nature of its success. While praised as an excellent example of adaptation and for its convincing portrait of postwar Montreal, the production was also harshly criticized for its casting of American actors in principal roles (save for Micheline Lanctôt as Yvette) and for its decidedly commercial Hollywood style.

Debates about cultural politics aside, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz remains an often engaging and occasionally complex film. It also received generally positive reviews in the United States. Variety wrote that “Ted Kotcheff has taken Mordecai Richler’s novel by the scruff of the neck and worked a zesty but somewhat muted nostalgic look at a nervy Jewish kid on the make in the 1940s.” In his review, Roger Ebert wrote, “It’s a little too sloppy, and occasionally too obvious, to qualify as a great film, but it’s a good and entertaining one.” Vincent Canby of the New York Times was more forthright with his praise, calling the film a “funny, fantastic and often moving story” with “an abundance of visual and narrative detail.”

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz was named one of the top 10 Canadian films of all time in polls conducted by the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in 1984 and 1993. In 1996, it was one of 10 films honoured with postage stamps by Canada Post to commemorate 100 years of Canadian cinema. In 2002, it was recognized as a Masterwork by the AV Preservation Trust.

In 2013, a restored digital print of the film struck by the Academy of Canadian Cinema & Television had a limited release in Canada and the UK, and screened at the Cannes Film Festival as part of its Cannes Classics program. In October 2016, the film was named one of 150 essential works in Canadian cinema history in a poll of 200 media professionals conducted by TIFF, Library and Archives Canada, the Cinémathèque québécoise and The Cinematheque in Vancouver in anticipation of the Canada 150 celebrations in 2017.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom