On 8 November 1861, seven months after the onset of the American Civil War, American Captain Charles Wilkes stopped RMS Trent, an unarmed British ship, in international waters between Cuba and the Bahamas. He took two Confederate envoys prisoner. The incident led to a diplomatic crisis between Britain and the United States that nearly led to a war that would have involved Canada. The Trent Affair was peacefully resolved when the two envoys were released on 1 January 1862 and allowed passage to Britain.

Background

The American Civil War began on 12 April 1861. The leaders of the southern states that had seceded from the United States to form the Confederate States of America hoped that Great Britain and France would ally with them. Both, however, declared themselves neutral. American President Lincoln imposed a blockade on Southern ports that cut off Europe’s vital cotton supply and on 21 July, the Confederates won the war’s first major battle — called Bull Run in the North and Manassas in the South. Britain and France still maintained their neutrality.

In August, Confederate president Jefferson Davis appointed two special envoys, former US Senate Foreign Relations Committee chair James Mason and former Louisiana senator John Slidell. He tasked them with travelling to Britain and France to persuade those governments to recognize the Confederacy as a sovereign state so it could more legitimately conduct diplomacy, raise funds in international markets, and secure alliances. The two envoys, their personal secretaries, and Slidell’s family were secretly transported to Cuba. Carrying secret documents authenticating their missions, they boarded RMS Trent, a small, unarmed British ship serving as a mail packet.

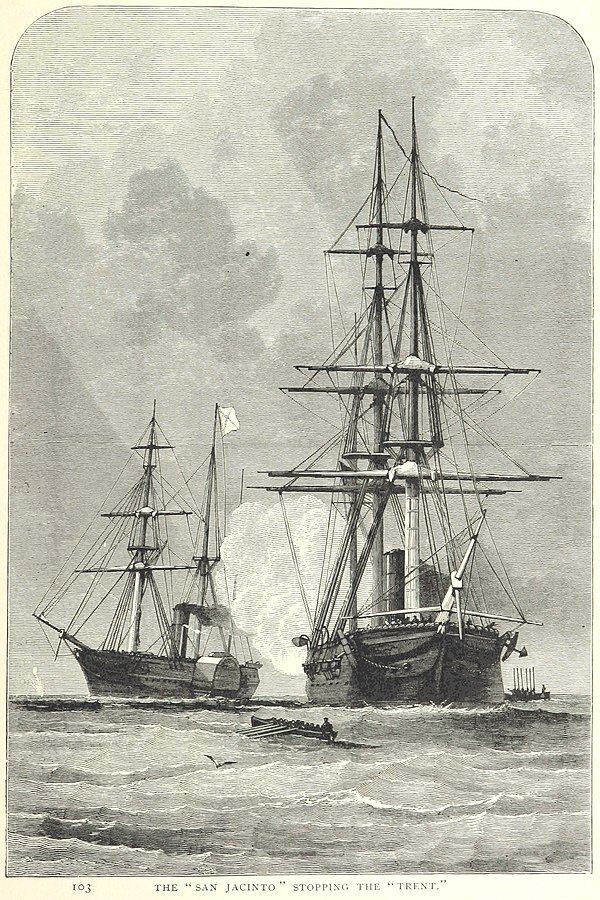

The Capture

On 8 November, Trent was in international waters in the Bahama Channel. Captain Charles Wilkes of the American sloop San Jacinto spotted Trent and fired two shells across its bow. Trent captain James Moir had no choice but to allow American sailors to board and search his ship. When Mason and Slidell stepped forward and identified themselves, they were placed under arrest and transferred to San Jacinto. Trent was allowed to continue its voyage. A week later, Mason and Slidell were in a stockade at Boston’s Fort Warren.

Captain Wilkes was welcomed as a hero and celebrated with dinners and a parade in New York City. However, when news of the seizure reached England on 25 November, the British press joined political leaders in expressing outrage.

The Crisis

British prime minister Lord Palmerston ordered shipments of saltpeter to the United States to be halted. (Saltpeter, or potassium nitrate, was an important component of gunpowder.) A letter was sent to American Secretary of State William Seward stating that Captain Wilkes’ action had violated international law and offended Britain’s honour and that the American government must release Mason and Slidell and issue a public apology to Britain.

Seward’s special representative in London reported that the consensus in “high places” was that Seward had ordered Wilkes to board Trent “to provoke a war with England for the purpose of getting Canada.” Palmerston knew that the crisis could lead to war and that Canada would be a battlefield in that war. While his letter to Seward was making its way to Washington, he dispatched thousands of British soldiers, artillery and war matériel to bolster the Canadian border. Meanwhile, American troops were moved to the border.

Canadian Governor General Monck ordered Canadian troops and supplies to the border. Additional workers were assigned to the construction of new batteries in Toronto and Montreal to expedite their completion. Canadian prime minister John A. Macdonald ordered the mustering, equipping and expansion of militia units. By the middle of December, 38,556 Canadian militia soldiers were armed and ready to defend against what was believed to be an imminent American invasion.

Macdonald sent Inspector General Alexander Galt to Washington. Galt met with President Lincoln on 4 December. The president made no direct threat but ominously warned that the American people wanted action regarding the threats from Britain and Canada and said, “We must do something to satisfy the people.”

On Christmas Day, the American cabinet debated the crisis for four hours. While some argued that Mason and Slidell should be released, others — including the president — were initially opposed. When the cabinet met again the next day, however, they decided to release Mason and Slidell but offer no apology. The American letter outlining the deal was received in London on 8 January and Prime Minister Palmerston agreed to its terms.

The crisis had demonstrated how quickly the Civil War could escalate into a broader international conflict and spill over America’s northern border into Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom