The 1793 Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada was the first legislation in the British colonies to restrict the slave trade. The Act recognized enslavement as a legal and socially accepted institution. It also prohibited the importation of new slaves into Upper Canada and reflected a growing abolitionist sentiment in British North America.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

Catalyst to the Act

On 14 March 1793, United Empire Loyalist Sergeant Adam Vrooman violently bound Chloe Cooley, a Black woman he enslaved, with a rope. (See also Loyalists in Canada.) He was assisted by two other men — his brother Isaac Vrooman and one of the five sons of United Empire Loyalist McGregory Van Every. The men put Cooley in a boat and transported her across the Niagara River to sell her in New York State. Cooley resisted fiercely, but to no avail.

Cooley’s piercing scream alerted Peter Martin, a Black Loyalist formerly enslaved by John Butler, to what was transpiring.

Peter Martin, a veteran of Butler’s Rangers, along with witness William Grisley, reported the incident to Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe and the Executive Council of Upper Canada in Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario). Grisley, a white resident of nearby Mississauga Point and employee of Sergeant Vrooman’s, was able to provide a detailed account of the events as he was on the boat that transported Cooley but did not assist in restraining her.

Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe used the Chloe Cooley incident to introduce legislation to abolish slavery in Upper Canada.

Enslavement in Upper Canada

British abolitionists such as William Wilberforce, James Ramsay, Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson had argued against the Atlantic slave trade since the 1770s. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada.) Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe had been influenced by the growing abolitionist movement prior to his arrival in Upper Canada in 1791. By then, abolitionists of African heritage were also playing a vital role in the struggle. Olaudah Equiano (also known as Gustavus Vassa), once enslaved in England, published his autobiography in 1789 and toured the United Kingdom to speak out against the inhumanity of enslavement. These abolitionist opinions spread to Upper Canada, where Simcoe and Attorney General John White led the call for abolition in the province.

However, the status of enslaved people was not recognized under English law. Unlike French civil law, which provided limited protection to the enslaved under the Code Noir, British law treated Cooley and other slaves as property, which meant that she did not have any rights as a person and could be legally sold just like any other object. The decision in the 1772 case Somerset vs. Stewart, which had rendered enslavement illegal in England, did not apply to British colonies. Enslaved Black persons were bought and sold alongside household furniture and farm animals. They were also bequeathed to heirs in wills and given as gifts. The lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada could do little against the “property rights” of enslavers within the confines of the law.

Enslavement had expanded sharply in Upper Canada following the American Revolution and was legally and socially accepted. In fact, Britain extended legal protection to slavery in the colonies to encourage settlement. The 47th Article of Capitulation of 1760 allowed French inhabitants to keep their slave property under British rule (see Capitulation of Montréal 1760). The Imperial Act of 1790 encouraged settlers to bring the Black people they enslaved into the colony duty-free. Loyalists subsequently brought approximately 2,000 enslaved Blacks with them to Canada — between 500 and 700 to Upper Canada. The law enforced and maintained enslavement through contracts — transactions that involved buying, selling or hiring out enslaved persons were legally binding, as were the terms of wills in which slaves were bequeathed.

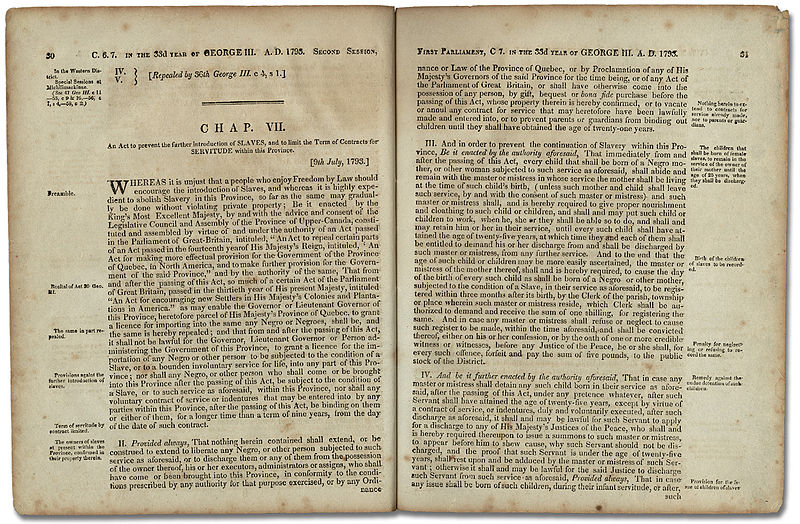

Following the Chloe Cooley incident, on 19 June 1793, Attorney General John White introduced an abolition bill to the House of Assembly, which he said received “much opposition but little argument” from government slaveholders. Between 1792 and 1816, several colonial officials and politicians enslaved Black people in the province. The Provincial Secretary William Jarvis enslaved six people. From the First Parliament of Upper Canada through to the Sixth Parliament of Upper Canada, three members of the Executive Council, 10 members of the Legislative Council and 20 members of the Legislative Assembly held property in slaves. Three politicians came from direct ancestors (father or grandfather) who enslaved Black people in Upper Canada. After going through the legislative process, the government brokered a compromise and passed An Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude (also known as the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada). Simcoe gave the bill Royal Assent on 9 July 1793 and expressed his hope that those who were enslaved “may henceforth look forward with certainty to the emancipation of their offspring.”

The Act Enacted

No enslaved persons in the province were freed outright as a result of the enacted legislation (see Black Enslavement in Canada). Though the Act prohibited the importation of enslaved persons into Upper Canada, it did not prevent the sale of slaves within the province or across the border into the United States. Newspapers in the province continued to publish advertisements of enslaved people for sale and requests for slaves to purchase. One of the last recorded sales of an enslaved person in Upper Canada took place in March 1824 when Eli Keeler of Colborne sold 15 year-old Tom to William Bell in Thurlow (now Belleville, Ontario). Many enslavers in Upper Canada continued to sell enslaved people in New York State until 1799, when a similar legislation was passed to gradually abolish slavery in that state.

The Act stated that enslaved persons who were in the province at the time of its enactment would remain the property of their enslavers for life, unless manumitted (freed). Children born to enslaved women after 1793 would be freed when they reached 25 years of age. Children born to this cohort were free at birth. Enslavers were required by law to provide food and clothing to the young children they enslaved. In addition, the Act required that former slaveholders provide security for recently freed slaves by ensuring that they were held in trust by a local church or town warden so as not to become a public charge (a person who depends on the government for assistance). This measure encouraged enslavers to employ their former slaves as indentured servants. The maximum term for an indenture contract was nine years and could be renewed. Structured as it was, the Act set the course for the abolition of slavery after one generation.

Impact

This legislative change was precipitated by Chloe Cooley’s scream. The Act was the first and only piece of legislation to limit enslavement in the British Empire until 1833, when An Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies; for promoting the Industry of the manumitted slaves; and for compensating the Persons hitherto entitled to the Service of such Slaves (later called the Slavery Abolition Act) abolished enslavement in all British holdings, including Canada, as of 1 August 1834. Freedom was celebrated on what came to be known as Emancipation Day, or August First.

The Act to Limit Slavery also signalled a growing shift in attitudes toward slaveholding in British North America, and contributed to the beginnings of an anti-slavery movement in Upper Canada. Yet, the Act added to the complex social status of Black people in the province. There were hundreds of enslaved Black persons who were deemed chattel property (personal property) and who did not have any rights or freedoms. There were also some free Black persons — less than 50 — who were primarily Black Loyalists, men who fought in the British Army during the American Revolution and were freed for their service. They had legal rights as British subjects, but often these rights and freedoms were limited by racial barriers. Due to the Act, there were soon freeborn Black subjects in Upper Canada. Meanwhile, a trickle of refugees from enslavement in the United States began to enter the province. In short, there were people of African descent with conflicting statuses living in close proximity to one another — at times within the same family.

The Act to Limit Slavery and the Slavery Abolition Act set the stage for the extension of the Underground Railroad farther north into Canada. As freedom seekers became free upon arrival in Upper Canada, many enslaved African Americans made the difficult passage north. Though exact figures are not certain, it is believed that as many as 30,000 refugees from American enslavement found freedom in Canada either by way of the railroad or on their own. The railroad's traffic reached its peak between 1840 and 1860 and particularly after the United States passed the Fugitive Slave Act on 10 September 1850.

Key Words

Abolitionist – A person who wants to make slavery illegal. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada.)

Chattel Slavery – In chattel slavery a Black person is treated like personal property that can be bought, sold or inherited. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada.)

Indentured Servant – A person who is contracted to work in order to repay a debt.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom