Peter Martin, loyalist, soldier (born c. 1753; died before 1816). Martin was one of at least twenty noted Black Loyalists who relocated to Upper Canada after the American Revolution and was one of many Black inhabitants in Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario). (See also Black Loyalists in British North America.) Martin was instrumental in reporting the Chloe Cooley incident to the Executive Council of Upper Canada, which influenced the creation of the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada.

Black Loyalist

Peter Martin, also formerly known as Martin Stout, was a Black Loyalist who relocated to Upper Canada at the end of the American Revolution. It was common for enslaved people to have different names – the names assigned to them by their enslavers and the names they chose to adopt, especially in freedom. He was formerly enslaved by John Butler in New York. Martin was a veteran of Butler’s Rangers, a militia unit of the British military. According to existing records of Peter Martin’s testimony in his 1797 petition to the government of Upper Canada as well as in a 1796 petition of Colonel John Butler, he and his brother Richard Stout were born into slavery and were enslaved by Butler and his family near present-day Fonda, Montgomery County, New York. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada.)

Peter Martin and his brother Richard Stout served in Butler’s Rangers for four and a half years. They were manumitted (set free) for their service, as promised in Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation. (See also Black Loyalists in British North America.) Martin also received a 300-acre land grant in Niagara for his military service. Richard Stout passed away shortly after he was discharged at the end of the American Revolution in 1783 before a land grant was awarded to him. However, Richard’s land grant entitlement would serve an important purpose for Martin in 1797.

Peter Martin and Richard Stout were two of at least twenty Black Loyalists who had relocated to Upper Canada. The brothers were also two of many Black inhabitants in Niagara, the majority of who were enslaved. The complex realities of these two different social statuses of Black people in the province, impacted Black families in Upper Canada, including Martin’s family. (See also Black Canadians.)

Family Life

Peter Martin had other family members with him in Niagara. He was the father of two children who remained enslaved by the Butler family (see Black Enslavement in Canada). The baptism of his daughter Jane was conducted and recorded by Reverend Robert Addison of St. Mark’s Anglican Church in 1793. The baptismal entry from 6 January 1793 reads: “Jane, a daughter of Martin, Col. Butler's Negro.” Martin’s young son George was also held in bondage by the Butler family. Martin was persistent in trying to secure his children’s freedom, who Butler bequeathed to his own children and grandchildren in his will. Butler willed Jane to his granddaughter Catherine and George to his grandson John Butler. Both grandchildren were the offspring of Butler’s son Thomas Butler. Butler also left an enslaved woman named Pat to his son Andrew Butler. Given the circumstances, it is likely that Pat was the mother of both of Martin’s children or just the mother of Jane. It is not known what became of Jane. However, George Martin’s plight is documented in his father’s 1797 petition and later in George’s own 1816 land petition.

In 1797, Peter Martin arranged to purchase his son George from Thomas Butler. Colonel Butler had passed away in May 1796. Martin petitioned the Lieutenant Governor for the land grant that his deceased brother Richard was entitled to for his military service. In his petition Martin explained that he wanted to sell the land to raise the sum of £60 N.Y.C. (New York Currency) to buy the freedom of his enslaved son. Martin was awarded a land grant of 300 acres and presumably Martin was successful in purchasing his son’s freedom. Fifteen years later, George Martin enlisted as a private in the Coloured Corps and fought in the War of 1812.

Chloe Cooley and the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada

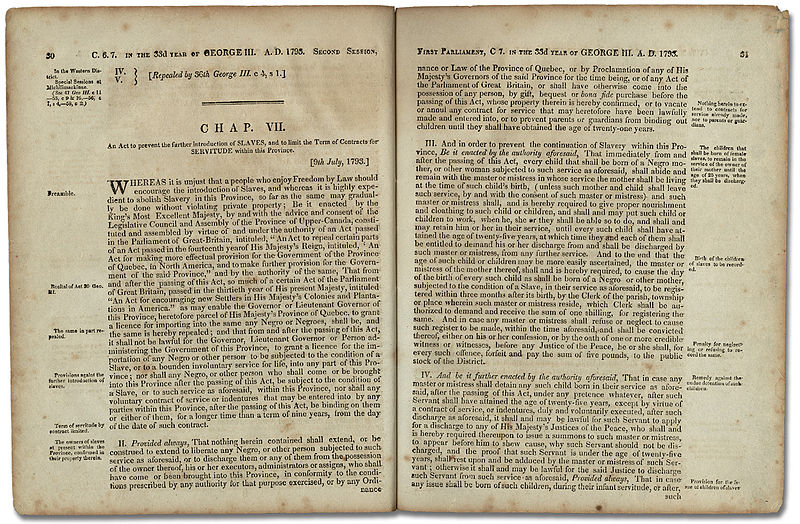

Peter Martin was instrumental in informing the Executive Council of the Parliament of Upper Canada about the violent removal and sale of Chloe Cooley, a Black woman enslaved in Niagara. He witnessed the incident and along with a white man named William Grisley, reported it to the members of the senior legislative body. This led to the introduction of legislation to gradually abolish slavery in the province, the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada.

Living in Freedom

Shortly after securing his son’s freedom, Peter Martin moved to the Town of York (Toronto). Martin was enumerated (counted) in the city’s 1801 census with another male, likely George. He was again counted among the residents of the Town of York the following year. After 1802, Peter Martin fades from historical records. He is later mentioned in an 1816 land petition from his son George Martin who was seeking land as a child of a veteran of the American Revolution. According to George’s 1816 petition, his father had died. Where Peter Martin died and the cause of his death are unclear. It is possible that his physical condition may have contributed to his death as he was described as “infirm” in his 1797 land petition. Peter Martin was disabled from an illness or injury that he may have sustained in the war.

Peter Martin’s pursuit of freedom led to freedom for himself and some of his family members. While unable to influence the freeing of Chloe Cooley, Martin’s actions contributed to the introduction of a new law that paved a pathway to freedom for African American freedom seekers. (See also 1793 Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom