The Airbus Affair was a political scandal that began in the late 1980s and concluded around 2010. The scandal concerned the purchase of Airbus passenger aircraft for Air Canada in the 1980s (when it was a crown corporation) by the government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. It was alleged that German Canadian businessman Karlheinz Schreiber had bribed Mulroney to purchase Airbus aircraft. Mulroney countered that he had not acted inappropriately and that the allegations were part of a smear campaign. Mulroney sued the federal government for $50 million. Ultimately, the RCMP ended its investigation without laying charges. The government settled out of court with Mulroney in 1997. However, it was later determined that Mulroney had indeed acted inappropriately and had received at least $225,000 in cash.

Airbus Deal

During Brian Mulroney’s term as prime minister, Air Canada was a crown corporation — a public company owned by the federal government. It had mainly purchased American, British and Canadian airplanes for its fleet.

Air Canada needed a new fleet of regional airliners. Airbus, a multinational European aircraft manufacturer, was having difficulties entering the North American airline market. At the time, the market was dominated by American aircraft manufacturers, namely Boeing, which also supplied Air Canada most of its aircraft.

In 1988, when Mulroney was prime minister, Airbus won the Air Canada contract to supply 34 Airbus A320 planes for $1.8 billion.

In 2008, secret American documents revealed that Airbus’s efforts to get Canadian government officials to purchase their aircraft began as early as 1979. These efforts ramped up after 1984, when Mulroney was in office. The same report alleged that former Newfoundland premier Frank Moores came up with an intricate strategy to secure the Airbus deal. The company’s sale of aircraft to Air Canada would serve as a way for it to enter the lucrative North American market.

One part of this arrangement was convincing Canadian aviation entrepreneur Max Ward to purchase Airbus A310-300 long-range, wide-body airliners instead of its American competitor, the Boeing 767. Ward did ultimately buy these aircraft, receiving both a generous financing arrangement and an exclusive route and landing rights at Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris. These aircraft were eventually sold to the Canadian Armed Forces in 1992. They became the CC-150 Polaris strategic transport and refueling aircraft.

Karlheinz Schreiber

Karlheinz Schreiber is a German Canadian citizen known primarily as a businessman, lobbyist, fundraiser and arms dealer. At the time he was alleged to have been involved in the Airbus Affair, Schreiber was based in Calgary. He had a long history of fundraising for the Alberta Progressive Conservatives. He also had business ties with several large European industrial firms, such as Airbus and Thyssen.

Schreiber is alleged to have been at the centre of the Airbus Affair. He was accused of paying bribes to Mulroney worth $300,000 to secure the Air Canada contract for Airbus. Schreiber claimed that he paid the bribe out in three payments of $100,000 each, and that Mulroney received the first installment on 27 August 1993. This was after he was prime minister but while he was still a Member of Parliament. Allegations that Mulroney had received kickbacks from Airbus can be traced as far back as 1989.

Karlheinz Schreiber enters the Ontario Superior Court

Karlheinz Schreiber enters the Ontario Superior Court in Toronto 29 May 2000, for a hearing. Schreiber was fighting attempts by Germany to extradite him on allegations of tax evasion, breach of trust and bribery.

(photo by Aaron Harris, courtesy Getty

Images)

RCMP Investigation

On 29 September 1995, a lawyer from Canada’s justice department sent a letter to Swiss authorities asking for help in their investigation of the alleged corrupt activities of Karlheinz Schreiber, Frank Moores and Brian Mulroney. On 8 November 1995, Mulroney’s lawyers contacted then-justice minister Allan Rock, objecting to the wording of the letter sent to Swiss authorities. Later that same month, the situation was first detailed in major Canadian newspapers.

On 20 November 1995, Mulroney filed a $50-million defamation suit against the Government of Canada. In July 1996, a federal court determined that the RCMP’s letter to Swiss authorities had violated Schreiber’s constitutional rights. This suspended the RCMP’s investigation. In January 1997, the justice department reached an out-of-court agreement with Mulroney on the defamation issue. However, this did not suspend the RCMP’s investigation into the Airbus Affair.

In May 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada determined that the Canadian government had acted properly by appealing to Swiss authorities for help. (See also Schreiber Case.) By 1999, it was known that Schreiber had a coded system for identifying his Swiss bank accounts. That same year, a German newspaper revealed Schreiber had paid out millions of German marks in bribes to high-ranking members of the Christian Democratic Union party — one of Germany’s most powerful political parties. This became one of the biggest political scandals in German history. It led German authorities to demand Schreiber’s extradition.

On 22 April 2003, the RCMP announced the end of their investigation into the Airbus Affair. Later that year, in November, the public first became aware of the $300,000 Schreiber had given Mulroney. In 2005, Schreiber was extradited to Germany to face charges of tax evasion, bribery and fraud.

Aftermath

The federal government settled Mulroney’s defamation lawsuit out of court in 1997. It issued a payment to Mulroney for damages and to cover his legal expenses. An investigation by the CBC’s The Fifth Estate later determined that Mulroney had met with Schreiber in a hotel in Zurich in 1998 to determine whether Schreiber had any remaining evidence that could implicate him.

The scandal also led to an in-depth examination of the lobbying activities of Karlheinz Schreiber. While Schreiber was never convicted of any crime in Canada, the investigation ultimately revealed his illegal activities in Germany, prompting an immense political scandal there. The RCMP’s investigation further revealed evidence of Schreiber’s possible involvement in two other endeavours to develop business in Canada for German companies: lobbying the Canadian government to buy Eurocopter helicopters for the Canadian Coast Guard, as well as a plan to build an armoured vehicle plant in Cape Breton to help German industrial giant Thyssen get around arms control laws in Germany.

During the federal ethics committee investigation in 2007, Mulroney admitted to receiving cash payments from Schreiber but insisted this only occurred after he had left office in 1993. Mulroney also stated that he had only received $225,000, and that this was paid to him for lobbying he had done on behalf of Thyssen. Mulroney further admitted to waiting until 1999 to declare the earnings on his taxes. Schreiber contested all of these points in his testimony to the same committee, insisting Mulroney had received $300,000 in cash while he was still prime minister (a major violation of ethics), and that the money was in exchange for lobbying the Canadian government, rather than foreign governments.

Former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney

Former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney prepares to testify before the House of Commons ethics committee in Ottawa, Ontario, 13 December, 2007 about his dealings with German-Canadian businessman Karlheinz Schreiber.

(GEOFF ROBINS/AFP courtesy Getty Images)

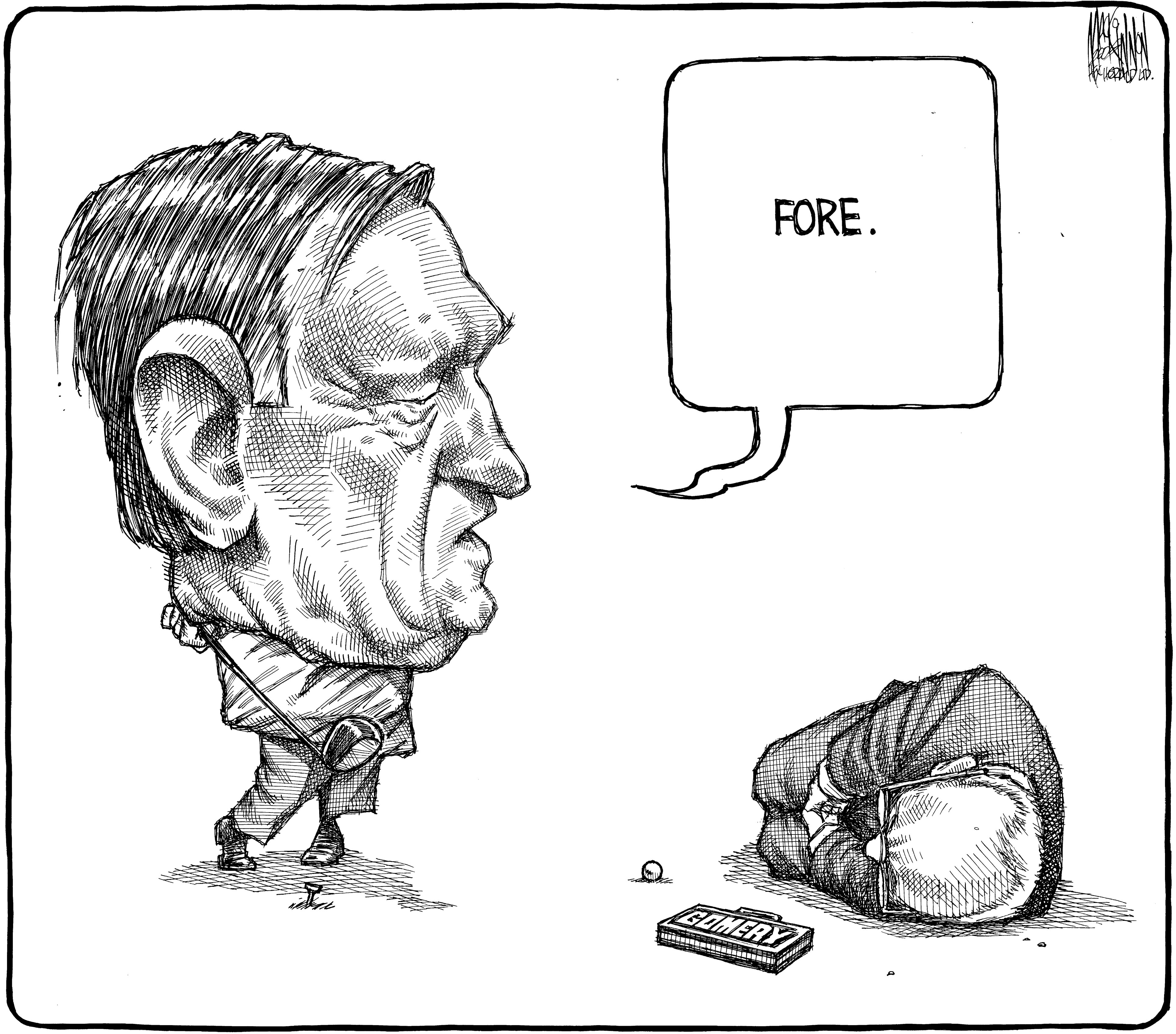

Oliphant Commission

The final chapter in the saga was the Oliphant Commission. It was conducted in 2008–09 and issued its final report in 2010. The commission focused on the business dealings and relationship between Schreiber and Mulroney. The Oliphant Commission was not mandated to determine whether civil or criminal laws had been broken. But it nonetheless determined that Mulroney and Schreiber had an inappropriate business relationship; that they had colluded to hide their business dealings from the public and from Canadian tax authorities; and that Mulroney had indeed received at least $75,000 in cash from Schreiber on three different occasions (at least $225,000 in total) for no other discernible reason. The report further determined that Mulroney had repeatedly acted in an inappropriate fashion by not disclosing these payments.

(See also Schreiber Case; Political Corruption.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom