The Arctic Ocean is a body of water centered approximately on the north pole. It is the smallest of Earth’s five oceans. Its boundaries are defined by the International Hydrographic Organization, although some other authorities draw them differently. Depending on which definition is used, waters of Canada’s Arctic Archipelago are included as part of the ocean, as are major Canadian bodies of water such as Baffin Bay, Hudson Bay and the Beaufort Sea.

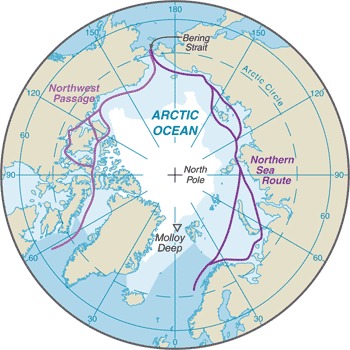

The Arctic Ocean, depicted here by the CIA World Factbook, is indicated in light blue. The purple lines indicate various sea routes.

Sea Ice and Climate Change

Compared to other oceans, the Arctic is less salty, mostly due to low rates of evaporation. However, its most distinguishing feature is its sea ice, which notably makes the ocean calmer by decreasing wave activity. The perennial sea ice layer — the area which remains frozen year-round — covers about a quarter of the ocean’s surface. In late winter and early spring, the entire ocean is covered in ice, including areas all the way down to Hudson Bay and James Bay. However, ice coverage is decreasing as a result of climate change. For example, the minimum extent of sea ice on the Arctic Ocean has decreased 12 per cent per decade since 1979, according the US National Snow and Ice Data Center. The “minimum extent” refers to the amount of sea ice on the ocean following warmer spring and summer temperatures, usually in the month of September.

This decrease in sea ice means that less sunlight is reflected by bright ice cover, and more of it is absorbed by the darker ocean. In turn, this leads to Arctic Ocean waters warming at an accelerated rate. Moreover, without ice coverage, winds are in direct contact with the water, creating waves. These waves increase erosion along the vast mainland shores and tens of thousands of islands in Canada’s North. However, wind patterns are such that they transport perennial sea ice from all over the Arctic Ocean to the northern border of the Canadian Arctic. Because of this, Canadian waters have lost less perennial sea ice than the rest of the ocean. In the future, this region may be the last to have summer sea ice.

Wildlife

Despite the harsh climate, the Arctic Ocean’s wildlife is diverse. The base of the food chain consists mostly of water-borne phytoplankton living off sunlight, but ice-dwelling sea algae also contribute. Over 220 species of fish live in Canadian Arctic waters, including some 20 which are anadromous, meaning they live in salt water, but swim to fresh water to spawn. Iconic Arctic mammals, such as beluga whales, narwhals and walrus, are also found in the Arctic Ocean. Many seabirds also participate in the ecosystem, including geese, ducks and loons.

Atlantic walruses partially submerged in Arctic waters.

However, the Arctic is changing rapidly. It is warming two to three times faster than the global average , causing many changes in species’ interactions with each other and their environment. These changes are numerous. For example, because there is less sea ice, algae which latch onto ice behave differently. They tend to bloom earlier in the season, in different locations than previously, and the distribution of algae species is changing. This can have repercussions throughout the entire food web.

History

Human exploration of Canada’s Arctic Ocean began about 5,000 years ago with the Sivullirmiut. These people, sometimes called Tunnit or Pre-Dorset, likely travelled from Siberia in search of new lands to inhabit. Four thousand years later the early Inuit (Thule), ancestors of today’s Inuit, were the main explorers of Canada’s Arctic.

Countless Arctic expeditions took place from the 15th century onwards, as Europeans sought to map the Arctic Ocean. One of the main goals was to find a way to navigate through Canadian Arctic waters from Europe to Asia, connecting the two continents by a relatively short route. This hypothetical route, called the Northwest Passage, was finally navigated successfully in 1906 by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. It continues to be an important shipping lane today.

Industry and Economy

Subsistence fishing has been a key part of Arctic cultures for millennia. The Inuit and their predecessors relied on ocean mammals, fish and invertebrates for food. This is still the case today for many Arctic coastal communities, although large-scale commercial harvesting is now practiced as well. Some major commercial species include northern and striped shrimp, Greenland halibut, and Arctic char. Other resources may soon be exploited too. For example, the Government of Canada has invested heavily in the exploration and mapping of the region’s oil and gas reserves. A moratorium on their extraction is in place, but it is reviewed every five years.

At the same time, due to slowly receding ice cover, the Arctic Ocean’s natural resources are gradually becoming more and more accessible. This will lead to increases in shipping, tourism, and economic development in Canada’s Arctic regions. These local activities affect the Arctic Ocean. For example, icebreakers modify their immediate environment as they navigate through sea ice. Increased shipping also means more shipwrecks and oil spills, especially because sea ice can cause serious damage to ships.

Did you know?

As climate change reduces sea ice on the Arctic Ocean and marine traffic increases, the Arctic faces air pollution problems particular to the region. This is because of a phenomenon called temperature inversion, which traps air in the lower atmosphere. Polluted air normally circulates in the atmosphere, and this reduces its potential impact. But in a temperature inversion, the air stays trapped, creating what is known as ice fog — air loaded with particulate matter stagnating in the lower atmosphere. Temperature inversions are particularly frequent and pronounced at high latitudes. The extent to which this phenomenon interacts with increased air pollution remains to be seen.

Politics

Eight countries surround the Arctic Ocean: Russia, Canada, the United States, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. Almost all Arctic land areas are definitively divided between these countries. However, sovereignty and economic rights over sea areas is a much more contested subject. In 2008, an agreement was signed between Denmark, Norway, Canada, Russia and the United States to attempt to divide up the ocean fairly. It followed the terms set out in the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention. Established in 1982, the Convention provides international guidelines regarding how oceans are used and by whom.

Essentially, a country bordering an ocean – including the Arctic ocean – is allowed exclusive economic rights over a zone extending 200 nautical miles (about 370 km) beyond its coasts. This means it has permission to explore and exploit non-living resources within that area. In addition, a country can be granted exclusive economic access beyond those 200 nautical miles if it can prove that these additional waters lie above its extended continental shelf. Because of this, all countries involved have scientists studying continental shelves in the hopes they can claim more of the resource-rich Arctic Ocean. For its part, Canada submitted a report to this effect to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in 2019.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom