The following article is part of an exhibit. Past exhibits are not updated.

While relations between Canada's West Coast and Asia were established during the fur trade era, the first real movement of people from Asia to Canada did not occur until the late 19th century. Drawn by the gold rushes and opportunities to work on the railways or in the mines, the first immigrants from China, Japan and South Asia were not welcomed by the largely Anglo-British society in Canada, who responded with discriminatory and racist measures.

This exhibit focuses on the struggles endured by the first generations of Asian immigrants in Canada. As we briefly touch on these stories — including immigration laws, ghettoization, race riots, the right to work and vote, and internment — we encourage you to click through to read more articles on the Encyclopedia in order to gain a broader view of this crucial corner of Canadian history.

See also the Asian Heritage in Canada collection page.

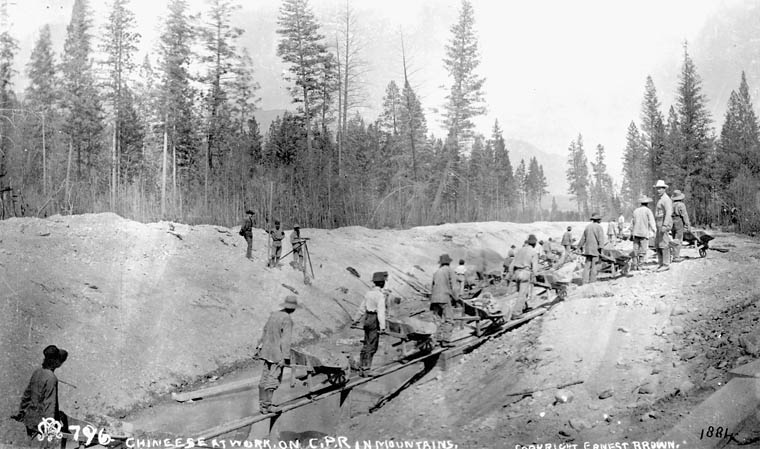

Railway Labour

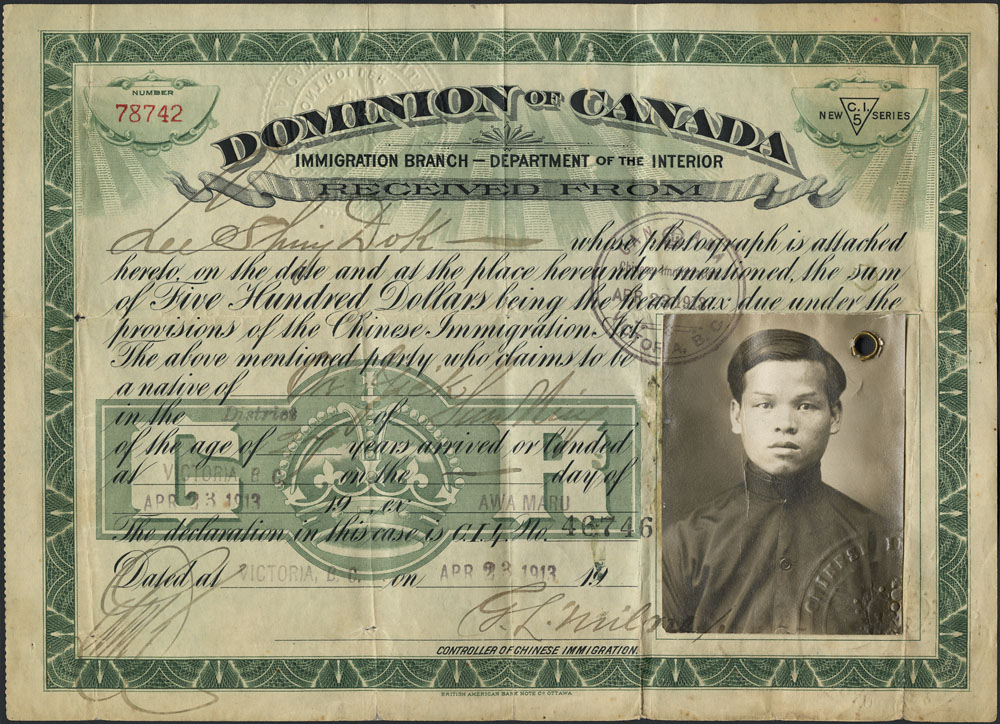

Despite Chinese Canadians' historic construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, many European Canadians were hostile towards Chinese immigration, and a prohibitive head tax restricted immigration from 1885 to 1923.

The Head Tax

From 1885, Chinese immigrants were obligated to pay a $50 head tax before being admitted into Canada. The Chinese were the only ethnic group to pay a tax to enter Canada. By 1900, in response to agitation in British Columbia, the government further raised the head tax to $100. The 1902 Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration concluded that Asians were "unfit for full citizenship ... obnoxious to a free community and dangerous to the state." In 1903 the head tax was raised to $500,* the number of Chinese who paid the fee in the first year dropped from 4,719 to eight. On 1 July 1923 (known to many Chinese Canadians as "Humiliation Day"), the Chinese Immigration Act was replaced by legislation that virtually suspended Chinese immigration. In 1947, the discriminatory legislation was finally repealed.

*Over $10,000 today

“The Pig Pen”

Some who stayed in them for as long as six months, dubbed them "pig pens" because of their cramped, prison-like exterior surrounded by a thick wall and barred windows. In Vancouver, authorities quarantined all arriving Chinese for three months in a low-rise building adjacent to the dock. It mattered not that each passenger had been examined aboard ship by a Canadian doctor; that they had been made to stand in line naked while they and their belongings were fumigated with sulphur. The building where arrivals were kept under guard was crowded and filthy inside.

Anti-Asian Riot

Hostility toward Asian immigrants erupted just five days ahead of the arrival of the SS Monteagle — a steamer carrying 901 Sikhs to the CPR pier in Vancouver — from Punjab, India. Whipped up by agitators from the Asiatic Exclusion League, a mob of 9,000 smashed windows and destroyed the homes and shops of Asian-Canadians in Chinatown and "Japantown." When the mob reached the Japantown section of Vancouver, they were driven away by Japanese immigrants who were veterans of the recent Russo-Japanese war.

Komagata Maru

When the ship arrived in Vancouver on 23 May 1914, most of the Komagata Maru’s Sikh passengers were detained on board. They waited for two months as officials maneuvered to keep them out of British Columbia. The arrival of the Royal Canadian Navy cruiser Rainbow on 20 July added to the pressure, and on 23 July the Komagata Maru sailed for Calcutta, where it was met by police. On disembarkation, 20 passengers were killed in a shooting exchange.

Labour Rights and the Vote

Asians were denied the right to vote: the Chinese in 1874; Japanese in 1895; and South Asians in 1907. But laws also excluded Asians from mining, the civil service and professions such as the practice of law, which required the practitioner to be listed on the provincial voting lists. Labour and minimum-wage laws ensured that employers hired Asian Canadians only for menial jobs or farm labour, and paid them at lower pay-rates than Caucasians. When Asians worked harder and longer to earn a living wage, white labour unions accused Asian Canadians of unfair competition, stealing jobs and undermining union efforts to raise the living standards of white workers.

Military Service

During the First World War, with a few rare exceptions, recruitment offices in BC would not accept Asians for military service. To circumvent this practice, over 200 Issei men (first-generation Japanese immigrants) travelled from BC to Alberta to enlist. Of the 222 who served, 54 were killed and 13 men received the Military Metal of Bravery.

Sikh Canadians also served with the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ten such men have been found among military records, all volunteers to fight for a country that denied them the right of citizenship. Among them, eight served in Europe, two of whom were killed in action. Another, who was wounded and died, was Buckam Singh, who was working as a farm hand in Rosebank, Ontario, when he was called for active service and joined the 20th Battalion.

Meet Private Buckam Singh, of one of the first Sikh Canadian soldiers. During WWI he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. In 1916 he served with the 20th Canadian Infantry Battalion in the battlefields of Flanders. His resting place in Kitchener, Ont., is now the only known WWI Sikh Canadian Soldier's military grave in Canada.

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Ethnic Enclaves

In Vancouver, restrictive covenants prevented the Chinese from buying property outside the Chinatown area until the 1930s. Contrary to stigma and stereotypes of Chinatowns as “overcrowded ghettos," the communities that developed in the 19th and 20th centuries were significant places for businesses and families. They became the heart and soul of Chinese Canada and were a safe bastion from the hostile and racist environment that surrounded them. In particular, Vancouver's Chinatown during the exclusion era (1923–1947) became a thriving economic and social destination that was home to many Chinese Canadians on the West Coast.

Internment

More than 8,000 were moved through a temporary detention centre in Vancouver, where women and children were detained in a livestock building. The detainees were shipped to camps near Hope, BC, and in the Kootenay Mountains, to sugar beet farms in Southern Alberta and Manitoba, and to road camps in BC and Ontario. Those who resisted were shipped to prisoner-of-war camps. Between 1943 and 1946, the government sold all Japanese-owned property — homes, farms, fishing boats, businesses and personal property — and deducted from the proceeds any social assistance received by the owner while in a detention camp. In December 1945 — a full year after the US permitted Japanese Americans to return to their homes — government defied Parliament and gave Cabinet the power to deport 10,000 Japanese Canadians to war-torn Japan.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom