History of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Evolving Concepts

Autism as a concept first emerged in 1911, when Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler coined this term to refer to particular behaviours (e.g., detachment from others) that he observed in adults with schizophrenia. However, it was not until 1943 that Austrian-American psychiatrist Leo Kanner recognized autism as a separate disorder with a pattern of behaviours that he called “early infantile autism.” He described individuals with autism as having difficulties with social interaction and communication and a great resistance to change. Kanner suggested that infantile autism differed from schizophrenia because of its early onset. While he acknowledged that early infantile autism may be genetic in origin, he also noted that unaffectionate, detached and obsessive parents may be to blame for the condition. This assertion remained highly contentious for years and was eventually discredited.

In 1944, Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger also described behaviours in children who showed inappropriate social interactions but had good language skills, which they used to talk only about a narrow range of topics of interest to them.

Definition and Diagnostic Criteria

For over a decade, autism remained poorly understood and its concept was disputed. In 1956, Leo Kanner and a colleague, Leon Eisenberg, proposed two essential criteria for the diagnosis of infantile autism: (1) a profound lack of affective contact (i.e., interactions driven by feelings) present by 24 months of age, and (2) elaborate, repetitive routines with intense resistance to change.

More than 20 years later, despite these efforts to define autism, infantile autism was first incorporated into an international diagnostic classification system as a subtype of schizophrenia. Finally, in 1980, autism became an officially recognized diagnosis in North America when it was included in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition (DSM-III) under a form of childhood onset disorders called pervasive developmental disorders (PDD). This was an important shift in conceiving autism as a developmental, rather than psychotic, disorder.

The concept of autism has evolved over the subsequent decades, with its changing criteria outlined in the different editions of the DSM and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases. The fifth edition of the DSM (published in 2013), made significant changes to the diagnostic criteria of autism, adopting the umbrella term autism spectrum disorder to describe three previously separate disorders: autistic disorder (also referred to as classic autism); Asperger syndrome (also known as Asperger’s syndrome or simply Asperger’s); and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS, also referred to as atypical autism). With this change, there was also a shift from three diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV (impairments in social interaction; impairments in communication; and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviour, interests and activities), to two in the fifth edition.

The DSM-5 defines autism spectrum disorder as a set of atypical neurodevelopmental conditions (as opposed to the “neurotypical” conditions present in the general population) characterized by persistent impairment in social communication and interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities. In addition, 45–90 per cent of children with ASD have sensory sensitivity, such as avoidance of sensory stimuli (e.g., noise) and more extreme (lower or higher) responses to sensory stimulation (e.g., touch and tactile sensations). Though these symptoms appear in the first few years of life, they can often go unnoticed until later in life when demands upon the child increase — for instance, upon entry into school. The communication and behavioural difficulties vary widely in severity and developmental course, resulting in great diversity in how ASD presents in each individual.

For example, language impairment, which has been linked to autism disorder diagnosis in the past, is now classified as a co-occurring condition, since a wide variation in language is seen among individuals on different ends of the autism spectrum. And because the DSM-5 classifies autism on a spectrum of wide variation in skills, it also includes specifiers such as “with or without accompanying intellectual impairment” and severity level to better address the needs for support. The most recent estimates of intellectual ability among youth with ASD suggest that approximately 31 per cent also have an intellectual disability, 25 per cent have low levels of cognitive functioning (but not an intellectual disability), and the rest have at least average intellectual ability.

Asperger Syndrome

Asperger syndrome (AS) first appeared in the DSM-IV in 1994. Unlike individuals with classic autism, most individuals with AS (as it was defined in DSM-IV) tend to have average to above-average intellectual functioning and appropriately developed language skills, while showing mild to severe impairments in social interaction and understanding, as well as having restricted and repetitive activities and interests. Because AS is less severe than classic autism and also varies significantly across individuals, it is more difficult to diagnose and has therefore resulted in more adult diagnoses.

In the two decades after AS appeared in the DSM-IV, clinicians came to embrace the view of autism as a spectrum that includes those with average intelligence who have social deficits seen in classic autism. As a result, in the next edition of the manual, the DSM-5 (2013), AS was replaced by the umbrella term autism spectrum disorder.

This was a significant and somewhat controversial shift — particularly for individuals with AS, which has generally been considered on the “high functioning” end of the spectrum. People with AS, who commonly self-identify as “Aspies,” have established a strong community (e.g., the Wrong Planet website) that predates the publication of DSM-5. They have expressed mixed reactions to the changes in classification. In online discussion forums, many Aspies have embraced the reclassification as a step toward building solidarity across the spectrum. However, fear, suspicion or rejection of the DSM changes have also been common. The reasons for these reactions vary: they include concerns about losing access to services or treatment, losing one’s Asperger diagnosis or identity, resistance to being grouped with individuals with more severe disabilities, and mistrust of the scientific community behind the decision.

According to the DSM-5, while many individuals who were previously assessed as having AS will now be classified as having ASD, some may more strictly meet the diagnostic criteria for social communication disorder, which involves difficulties in social communication and relationships, but does not include any repetitive or restricted patterns of behaviour, interests or activities.

Pervasive Developmental Disorders – Not Otherwise Specified

Pervasive Developmental Disorders – Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) was first used as a diagnostic category in the DSM-III-R (1987). It has been described as “atypical” autism, with severe and pervasive impairments in some areas (i.e., reciprocal social interaction, restricted activities and interests) but not quite meeting the diagnostic criteria for autism. Continued use of PDD-NOS diagnosis in the DSM-IV, which did not specify a number or type of criteria, led to a broadening of the autism spectrum to include a wide range in the type, number, pervasiveness and severity of problems.

In the DSM-5, ASD formally became the umbrella term replacing PDD-NOS, as it did with AS. Although it is not yet known how this broad diagnosis will impact the way individuals are identified and diagnosed, some data suggest that most children with autistic disorder as it was diagnosed in DSM-IV will continue to meet the DSM-5 criteria for ASD, while about 50–80 per cent of those with prior diagnoses of PDD-NOS will not meet the new criteria for ASD.

Savant Syndrome

Savant syndrome is a rare but remarkable condition in which people with various developmental disabilities (ASD and other central nervous system disorders, such as brain injury) have very specific and profound special skills along with massive memory, which is often considered photographic memory. The term autistic savant was popularized by the 1988 movie Rain Man, starring Dustin Hoffman as a man with autism who has specific intellectual gifts despite being otherwise childlike in his intellectual development.While the film appropriately depicts savant abilities (typically, exceptional skills in mathematics, music, art, calendar calculating or mechanical/visual-spatial skills), many people came to assume that all people with ASD have savant abilities and vice versa. In reality, only about 1 in 10 people with ASD has savant skills, and these skills are not limited to people with ASD. Moreover, savant syndrome can be present at birth or develop later in life following an injury or a disease, such as a blow to the head or dementia. Males are four to six times more likely than females to develop this condition, which is not a diagnosis listed in the DSM-5.

Dr. Darold Treffert coined the term savant syndrome, and also addressed some prevalent myths and misconceptions about it. First, he noted that individuals with savant syndrome tend to be creative, progressing from imitation to improvisation to creation. Treffert also noted that a low IQ is not necessary for savant syndrome and that IQ levels vary for these individuals. Finally, there is a difference between savant syndrome, which occurs in people with developmental disabilities, and “prodigy” or “genius,” which occurs in people who do not have ASD or any other developmental disability but display special and extraordinary abilities.

Signs and Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder

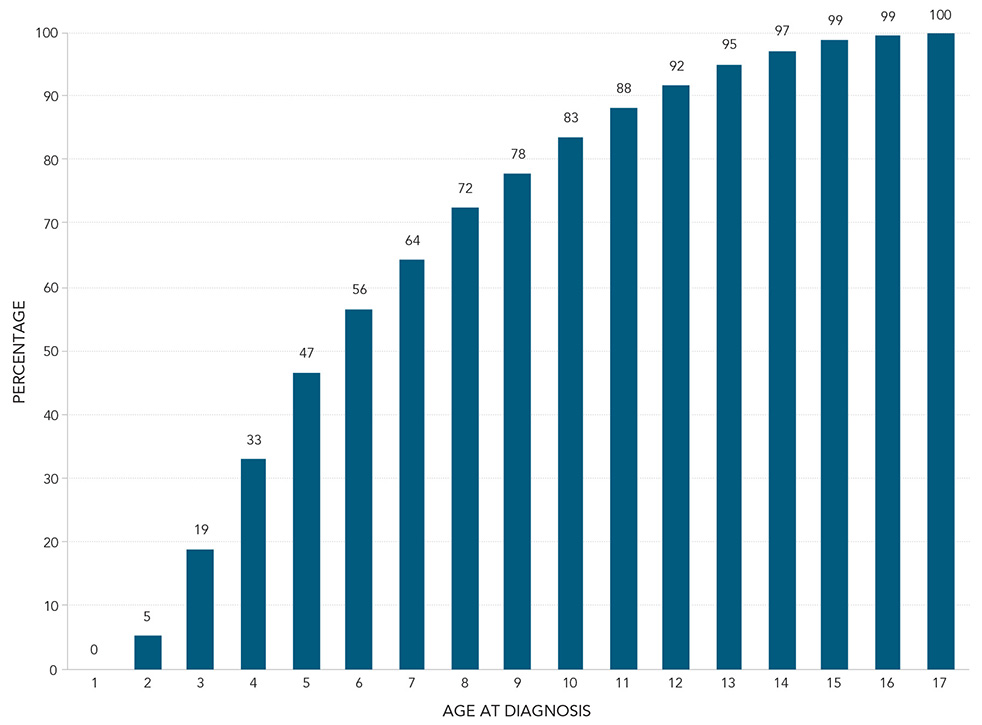

ASD symptoms are typically first recognized between 12 and 24 months of age, although these symptoms may be seen earlier than 12 months if developmental delays are severe, or later than 24 months if symptoms are subtler. Around this time, children may begin to exhibit developmental delays in, or losses of, social or language skills. For example, some children may show a lack of reciprocal smiling and looking at faces, a consistent lack of eye contact, or persistent hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input (e.g., an extremely low or high pain tolerance, negative responses to specific sounds or textures, or visual fascination with lights). As play develops, parents may notice that their child plays “differently” with toys, such as lining up objects (toy cars, for example) or carrying them around but never playing with them in the traditional sense. Children may also have restricted interests or a lack of interest in playing with others. Adaptation to change may be an area of significant difficulty; children with ASD may become extremely upset if their routine is changed.

Researchers in the field have developed a range of tools to screen for early symptoms of ASD. Currently, the most evidence-based and accepted screening tool for ASD is the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd Edition. This tool is play-based and has been developed to accurately assess and diagnose ASD across age, developmental level and language skills.

Causes and Risk Factors

While there is no single cause of ASD, there are certain environmental and genetic risk factors. Specifically, advanced parental age, low birth weight, or fetal exposure to the medication valproate (used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder) may contribute to the risk of ASD. Genetic research continues to explore heritability factors in ASD; currently, up to 15 per cent of cases are linked to a known genetic mutation.

A publication in 1998 by British gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield and his team suggested that there is a link between autism and vaccination with the mumps, measles and rubella (MMR) vaccine or with other childhood vaccines containing mercury in the vaccine preservative. Despite this study being retracted from the journal in which it was published due to ethical breaches and numerous studies thereafter showing no connection between autism and the MMR vaccine, media coverage of Wakefield’s theory fostered a widespread belief in a link between vaccination and ASD. (See also Vaccination Rates Are Plummeting.)

Research shows that there are some factors that can predict the severity of ASD. One is the individual’s cognitive functioning: those with higher cognitive function show significant progress over time in their adaptive and language skills. Early verbal and nonverbal communication can also predict better adaptive behaviour and communication skills. For instance, children with higher IQs and those who develop speech by five years of age tend to have better long-term outcomes.

Variation over Time

Unlike individuals with other developmental disorders, those with ASD, to varying degrees, are capable of learning and adapting to their disorder throughout life. Progress and developmental gains are typically seen throughout childhood in various areas (e.g., increased independent behaviours and interest in social interactions). This progress depends on the severity of the disorder and the degree of intervention these individuals receive.

Difficulties with social interactions become particularly clear as children with ASD enter school and have trouble interacting socially and verbally in age-appropriate ways. School demands also pose a challenge for children with ASD, who may have difficulties with impulse control and may exhibit disruptive behaviours in the classroom.

The social difficulties associated with ASD may be most disabling between preadolescence and young adulthood. Specifically, difficulties with verbal and nonverbal communication may become more prominent during this time of more frequent social interactions. Social challenges, along with the appearance of being aloof, may also create the impression that individuals with ASD are overtly blunt, insensitive, or have a disregard for the feelings of others.

Change is typically an area of significant difficulty for individuals with ASD. During adolescence and adulthood, demanding changes such as the transition from school to employment and leaving home may contribute to mental health issues such as depression and anxiety.

Dual Diagnosis

In Canada, the term dual diagnosis is used to describe an individual’s diagnosis of a developmental disability (e.g., ASD) and a mental health problem. (In contrast, in the United States, the terms dual diagnosis, dual disorder and co-occurring disorder are used interchangeably to refer to a concurrentmental illness and substance use problem.)

Individuals with ASD tend to use health services more frequently than people without ASD. They are also more likely to struggle with emotional and behavioural problems. For instance, in research on five-year-old children with ASD published in 2011, psychologist Vaso Totsika and colleagues found that compared to typically developing children, those with ASD have more hyperactivity, behavioural difficulties and emotional difficulties. These difficulties may increase as children get older. In Ontario, for example, 51 per cent of adults between the ages of 18 and 24 years with ASD also have a psychiatric disorder.

Prevalence

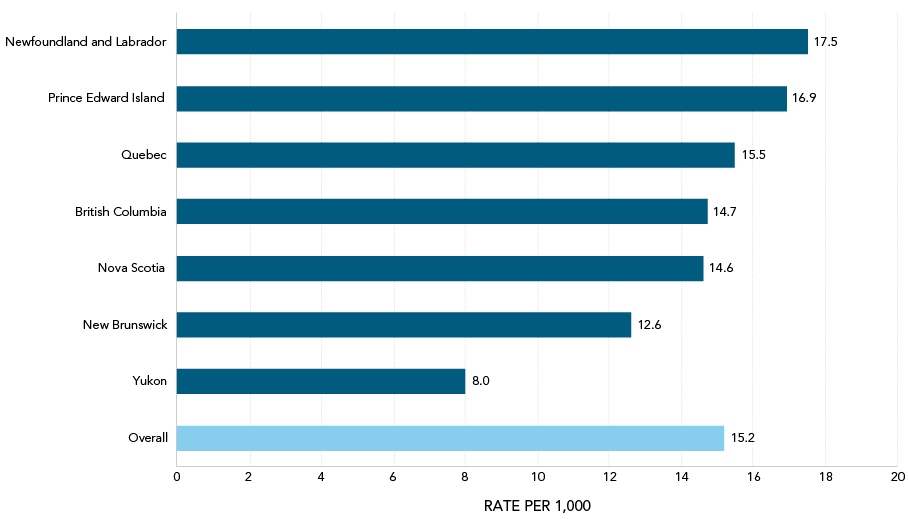

The prevalence of autism has been steadily increasing, with global rates rising from less than 1 in 500 people in the year 2000–01 to the current rate estimated by the World Health Organization of more than 1 in 160 people. In Canada, an estimated 1 in 66 children is diagnosed with ASD, according to a 2018 report by the Public Health Agency of Canada. However, it remains unclear whether higher rates reflect an expansion of diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV, increased awareness of ASD, differences in study methodology, or a true increase in frequency. The federal government has identified the need to systematically gather comprehensive, comparable data on ASD prevalence rates across the country. To this end, the Public Health Agency established an autism unit in 2011 to develop a “national ASD surveillance system.” As of 2018, however, this system was not yet in place.

Notably, ASD is diagnosed four times more often in males than in females. New research suggests that this is because ASD symptoms present differently in these populations. Many girls may go unrecognized or are misdiagnosed due to various factors, such as subtler manifestation of social and communication difficulties. It appears that for females to be diagnosed with ASD, their symptoms must be more severe or prominent. For example, in 2014, American psychologist Thomas Frazier and his colleagues found that girls who were given an ASD diagnosis were more likely to have low IQ and more severe behavioural problems. Another reason females may not receive an ASD diagnosis is that girls tend to have a greater ability to hide or “camouflage” their symptoms.

Treatments

Evolving Approach, 1960s–Present

As clinicians’ understanding of autism evolved over the 20th century, various approaches were developed to treat individuals with ASD. Some of these treatments are now recognized as ineffective, harmful or unethical. For instance, in the 1960s and 1970s, when the understanding of ASD was still limited, pain (e.g., shock therapy) was used as a form of punishment to alter these individuals’ behaviours.

In the past, Canadians with ASD were only seen within institutions such as mental asylums. Since the 1970s, such institutions have closed as a result of the shift to more specialized and evidence-based treatments. Scientists and clinicians began to emphasize community inclusion in Canada, with the expectation that individuals with ASD would access physical and mental health care in their local communities. Despite some progress, these health needs are still often underserved.

Today, there is a greater understanding of ASD and effective treatments, such as applied behavioural analysis, for its symptoms. Although behavioural analysis approaches grew in popularity and were increasingly supported by evidence during the 1960s, early forms of behavioural therapy for treating children with autism weren’t used until the 1980s.

Current Treatments

Early intervention is key for individuals with ASD. Research has widely shown that treatment is most effective before five years of age and that it continues to help individuals with ASD develop adaptive skills and promote their mental health.

While there is no single intervention that is universally recommended for treating ASD, general and specific supports have been developed. General supports include life-skills training, respite care for family members, independent living skills training, income subsidization and recreational programs. More specific treatment models that focus on ASD include diet plans (i.e., removing wheat and dairy products, which some believe impact behaviour), medical treatments and psychological models.

In Canada, these treatments are available through the public and private sectors, but wait times for psychological treatments are often long. In Ontario, for example, the wait-list for treatments like applied behavioural analysis (ABA), which the province has funded since 2011, increased by more than 400 per cent between 2005 and 2015. By early 2019, approximately 23,000 children in Ontario were on the wait-list for government-funded autism services and some were waiting years for treatment, missing crucial opportunities for early intervention. In 2019, the Progressive Conservative government of Doug Ford introduced a plan to clear the wait-list by providing families with a “childhood budget” to pay directly for services of their choice. This model somewhat resembles the direct-funding schemes of British Columbia and Alberta, where families typically wait less than a year for the same services. Critics of the changes in Ontario argue, however, that the plan does not sufficiently address the wide range of needs of children with ASD, the high cost of many therapy plans, and other barriers to treatment.

There are two main evidence-based, effective treatment approaches for individuals with ASD: behavioural approaches (e.g., ABA) and medication. Talk-based therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), are increasingly used with children who have high-functioning ASD. CBT has been helpful in addressing various symptoms in this population, including anxiety, aggression and impaired social skills. However, despite some promising research results for using CBT with individuals with ASD, further evaluation is necessary to establish its effectiveness.

Applied Behavioural Analysis

Applied behavioural analysis (ABA) is a highly effective technique that promotes social interaction, communication and self-care skills. It also helps manage behavioural challenges. This program has the strongest evidence of providing effective treatment for individuals with ASD. One of the central tenets of ABA is functional analysis, which involves assessing individuals’ problem behaviours to identify why they engage in those behaviours. ABA uses behavioural approaches to address individual difficulties one step at a time. For example, one skill targeted in therapy could be eye contact and joint attention. This skill would be practiced and reinforced for a set number of trials until the child has consistently acquired it and is then able to move on to learning another skill.

Despite its popularity among many clinicians and parents, ABA — and a version of this approach called intensive behavioural intervention (IBI) — have been criticized by some as causing pain or stress for children with ASD. Critics also hold that these approaches have the detrimental goal of changing the child’s mind and personality.

Medication

Medication is commonly prescribed for individuals with ASD. In fact, more than 75 per cent of these individuals take psychotropic medication by the time they reach adulthood. Growing up, the most common reason children and youth with ASD take medication is to treat their aggression. As they get older, however, medication is most frequently prescribed to address internalizing problems, such as anxiety and depression.

Education Programs and Mindfulness

Individualized education programs — such as segregated special education classes or mainstream general education classes (in which children with ASD are fully included) — have been used as treatments. Examples of such programs are the TEACCH Autism Program, in which children with ASD are educated together in classrooms separate from their typically developing peers, and LEAP, which uses an inclusive education approach. Both programs have proven effective in helping children with ASD make gains over time.

Recent research suggests that mindfulness-based approaches may also be effective in helping children and youth with ASD self-manage their physical aggression over several years and improve their mood and social interactions.

Despite much research, evidence related to treatment for individuals with ASD continues to be limited by factors such as the lack of thorough methodologies, of comprehensive ways to measure progress, and of consistent assessment tools.

History of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Canada

It was not until shortly following the Second World War that children with ASD were first seen for diagnosis and treatment in Canada. Universal health care, which was introduced across the country from the 1950s to the 1970s, allowed families to access diagnostic and treatment services for ASD more readily, regardless of their income level. This was a significant step in supporting this population. Dr. Milada Havelkova at the West End Crèche in Toronto, Ontario, was the first clinician in Canada to diagnose and treat children with ASD. She was also the first child psychiatrist in Canada to seek a better understanding of the causes of ASD through research. She published several influential papers on autism during her 30-year career at the clinic.

Diagnosis of ASD and other pervasive developmental disorders has steadily increased in Canada since their addition to the DSM-III in 1980, despite significant confusion between the terms autism, PDD and PDD-NOS among health professionals and the public. In 1987, the DSM-III-R broadened the criteria for autism. This further increased in the number of children who received a diagnosis of autism or PDD-NOS.

In the late 1980s, researchers focused on understanding the efficacy of ABA principles for very young children. Despite research supporting a minimum of 25 hours weekly of interventions for preschool children with autism, in Canada and elsewhere many diagnosed children continued to be underserved in the quantity as well as the quality of treatment. Significant advocacy has therefore been needed to influence social policies around ASD (see Grassroots Advocacy).

Throughout the 1990s, autism researchers focused on the molecular genetics of autism, as well as developing reliable and valid diagnostic tools. With the rising rates of ASD, researchers also explored the contribution of environmental risk exposures to the development of autism.

Scientists around the world continued to study the genetic basis of autism in the 2000s. In this country, the Canadian Autism Intervention Research Network, formed in 2001, united researchers, clinicians, parents and other professionals working to develop new diagnostic and treatment methods for Canadian children with autism.

Another important development in services and supports for children with ASD was the integration of children with disabilities within community settings. The school system has played a key role in integrating children with ASD into the educational mainstream, while providing special accommodations to support their special needs. For instance, in 2003, the Ministry of Education in Ontario hosted a province-wide conference, Teaching Students with Autism: Enhancing the Capacity of Ontario’s Schools, to improve the planning and implementation of special education programs and services at schools. The following year, the ministries of Education and Children and Youth Services partnered with school boards and community agencies to develop the School Support Program – Autism Spectrum Disorder. This program improved connections between school boards and ASD consultants to help school staff support students with ASD. Similarly, in British Columbia, the Autism Society of BC has been working since 1975 to support individuals with autism by promoting understanding, acceptance and full community inclusion. It does so through advocacy for these individuals’ rights, information packages and community support groups for families.

While many parts of Canada have come a long way in integrating children with ASD into regular classrooms, accommodations (or appropriate teacher training) are not always readily available and many children remain in segregated settings. Alberta has tackled this challenge differently than most of the other provinces by providing alternatives to mainstream education for individuals with ASD. Since the mid-1990s, Alberta Education has supported access to “schools of choice” and provided direct funding to assist children with developmental disabilities based on their unique needs. Options include special needs schools and a range of behavioural, speech and occupational therapies. The province’s Family Support for Children with Disabilities program determines the amount of funding each family receives. Among several advantages to this program is that parents have choices for appropriate treatment and the wait times for support are short.

Canada was the first country to address disability rights in its constitution as part of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The most notable development specifically related to autism policy in Canada was the Auton v. British Columbia case, in which parents of children with autism argued before the Supreme Court of Canada that the BC government was bound by rights guaranteed under the Charter to fund ABA and intensive behavioural intervention (IBI) in the province. In November 2004, the Court decided that the BC government did not violate the Charter by failing to fund autism treatment and determined that each province should independently decide whether to fund these therapies.

Calls for a National Autism Strategy

In 2006, federal health minister Tony Clement announced the creation of an autism research chair and a consultation process to establish a system for gathering data on ASD nationwide. While some hailed these efforts as the beginning of a national conversation on autism, critics argued that access to treatment and a concrete national strategy were more urgent priorities.

The next year, the Canadian Senate published a comprehensive report on autism funding titled Pay Now or Pay Later: Autism Families in Crisis. The study, launched by the Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology at the initiative of Senator Jim Munson, found that “governments must pay now for autism therapy, services and supports in order to obtain the greatest return on investment. Otherwise, they will pay later in terms of much higher costs in future years for welfare, social services and institutional care.” The report recommended that the federal government implement funding mechanisms and a national autism strategy, among other actions.

Formed in 2007 in response to the Senate’s report, the Canadian Autism Spectrum Disorders Alliance (CASDA) has continued to press for a national autism strategy that would bring changes to funding and other policies. Such changes, CASDA maintains, are crucial to ensuring equality for individuals with ASD and their families. In 2014, CASDA published a national needs assessment survey identifying what it called “the most complex issues affecting Canadians living with autism,” and it launched the Canadian Autism Partnership Project in 2015 to spur innovation and action on these issues.

In October 2017, the Senate marked Autism Awareness Month and the 10th anniversary of the Pay Now or Pay Later report by renewing its call for a national autism strategy. World Autism Awareness Day (2 April) has also been observed annually in Canada since federal legislation designated it in 2012.

Grassroots Advocacy

Public discourse on autism is complex, with some efforts focusing on celebrating this disability and others seeking to “cure” it. Various advocacy organizations throughout Canada have nevertheless made strides in educating the public about individuals with ASD and how best to work alongside them. One such a group is Autism Speaks Canada, an arm of the US organization Autism Speaks founded in 2005. Autism Speaks Canada has developed tools for police and other first responders who work with individuals with ASD and their families. Other national organizations devoted to people with ASD include Autism Canada (founded in 1976) and the Canadian National Autism Foundation (founded in 2000). Provincial and territorial autism societies are also active across the country.

In addition to serving as effective platforms for education and awareness, grassroots organizations have played a key role in supporting parents. Some also fill gaps in government support by offering recreational programming and direct treatment for children.

Self-advocacy organizations such as Canadian Autistics United and Autistics 4 Autistics Ontario have emerged to represent autistic adults in discussions often dominated by parents and providers. Part of the disability

rights movement, these organizations advocate for policy reforms and promote neurodiversity — the acceptance of differences between people’s brains and minds as natural and valuable in society.

Barriers to Care

Despite ongoing advocacy efforts in Canada and gradual changes in health care and education, people with ASD continue to struggle to access appropriate care due to systemic barriers (e.g., lack of funding, as discussed in Pay Now or Pay Later) and a lack of capacity (e.g., lack of sufficiently trained mental health professionals). Examining this lack of capacity, Dr. Jonathan Weiss and colleagues conducted a national Canadian survey of accredited clinical and counselling psychology graduate students, the results of which were published in 2010. This study showed that while most graduate students were willing to train to work with individuals with ASD, they felt that the training available in this subject was inadequate. With such shortfalls in the system, Weiss concluded that there remains a significant need for timely assessments and evidence-based interventions among individuals with ASD and mental health problems.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom