On 8 July 1758, a small French army of some 3,500 men commanded by General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm won an important victory over the 15,000 British troops of General James Abercromby at Fort Carillon. This unexpected outcome was attributable to the French general’s defensive strategy as well as the tactical errors made by the British. The Battle of Carillon has since become one of the most famous French victories in North America. It has left an indelible mark on the imaginations of the Québécois and inspired poets, as well as the design of the Quebec flag. (See also Seven Years’ War.)

Catastrophic Situation

The year 1758 opened badly for the French in Canada. Over the winter of 1757–1758, the British captured some 15 French ships sailing to New France. Resupply of the French colony was compromised, and its food situation became desperate. From a military standpoint, French officers were pessimistic, and supply shortages forced them to abandon any plans for an offensive campaign.

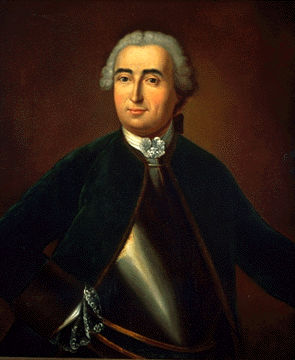

Canada appeared to be in its death throes, and the British government was determined to strike the final blow. It placed Major General James Abercromby in command of the largest army ever assembled thus far in North America: 15,000 troops, namely 6,000 regular troops and 9,000 militiamen. Abercromby favoured offensive tactics. At many times in his career he had criticized the lack of fighting spirit among his fellow officers. In July 1758, he planned the journey of this vast army and led it toward the junction of Lake George and Lake Champlain.

Prelude to Battle

Simultaneously, French general Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm arrived at Fort Carillon. The eight battalions of infantry that he had been sent were in pitiful condition. Brigadier Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, his aide-de-camp, criticized the “quantity of poor recruits” in these units. In total, the army had only 3,500 men, of whom about 3,000 were regular infantry. The rest consisted of a few Troupes de la Marine companies, militia and about 15 Indigenous allies. (See Indigenous Peoples in Canada.) Thus Montcalm did not have the 5,000 men that the governor of New France, Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, was supposed to send him.

On 5 July 1758, the French received reports that the British army had embarked on over 1,000 boats spread out across several kilometres of Lake Saint-Sacrement (now Lake George). The French sent 400 men, commanded by Captain Louis-Joachim de Trépezec of the Battalion of Béarn, out to meet them along Bernetz Brook. The next day, this French troop fell upon a British column at the La Chute River portage. A skirmish broke out in which the British second-in-command, General George Howe, was killed. This news shook the British and halted their progress for 24 hours. The French made good use of this time.

After this first shock, Montcalm consulted his officers about what defensive strategy to apply. Taking their advice, he decided not to defend the fort, but instead to occupy a high plateau that dominated its surroundings. On the morning of 7 July, Montcalm mobilized his entire force to build entrenchments designed by engineers Nicolas Sarrebource de Pontleroy and Jean-Nicolas Desandrouins.

Without further ado, the soldiers felled hundreds of trees, stripped off their branches and laid the trunks in rows in front of the entrenchments, sharpened ends outward, forming thick abatis. The French filled all the space in front of these fortifications with broken trunks, branches and debris of all kinds, forming a hard-to-penetrate obstacle that would slow the enemy advance. As night fell, these defences formed a 500-metre arc with a breastwork some 2.4 metres high, following the contours of the plateau. That night, the 400 troops of infantry sent as reinforcements by the Duc de Lévis arrived to a hearty welcome from the garrison of Fort Carillon.

The Battle of Carillon

On the morning of 8 July, the French troops hastened to complete the entrenchments. At about 10:00 a.m., the enemy vanguard appeared on the horizon. The French soldiers dropped their shovels, picked up their rifles, and began taking their positions. The infantry lined the abatis three rows deep. A unit of the Regiment of Berry remained in the fort, while 300 soldiers of the Troupes de la Marine and militia deployed north of the abatis, along Lake Champlain, and two units of volunteers took up positions to the south, between the entrenchments and the La Chute River. On the British side, James Abercromby positioned his men in four assault columns, deploying Anglo-American sharpshooters between them.

At about 12:30 p.m., the British assault began. Relying on the advice of one of his engineers, who had convinced him that the French position could be easily taken, Abercromby did not wait for his artillery or attempt to lay a conventional siege. This decision had serious repercussions. The Anglo-American militia deployed along the flanks of the abatis and opened fire, while the columns of Redcoats became hopelessly mired in the debris strewn in front of the abatis. Instead of charging through these obstacles, the British advanced painfully slowly, to the sounds of the bagpipes. The French commander ordered his men to hold their fire and let the British continue advancing until they reached the foot of the entrenchments, when he at last gave the order to shoot.

In the blink of an eye, over 3,000 rifles unleashed a murderous hail of lead on the assailants, who suffered heavy losses. For seven hours, the determined British continued to assault the fort in repeated waves that were mown down one after the other. To maximize their rate of fire, the French placed their soldiers who were the best shots in the front line and let those in the second and third lines reload their rifles for them. The resulting devastating fire from the French proved formidably effective. At one point, the British tried to outflank the abatis by descending the La Chute River in boats, but were repelled by the guns of Fort Carillon.

At about 5:00 p.m., two columns from Scottish Highland regiments attempted a final assault and achieved an unexpected breakthrough. They withstood the French fire and managed to scale the ramparts to engage the French in hand-to-hand combat. But soon the Highlanders were overwhelmed by the French reinforcements. As night fell, the British had failed to achieve a decisive penetration. At about 7:30 p.m., Abercromby reluctantly gave the order to retreat. The British hastily retrieved their wounded and withdrew to Fort George.

Aftermath

The Battle of Carillon produced many casualties. The British lost nearly 2,000 men killed or wounded, and the French slightly less than 400. Louis-Joseph de Montcalm expected the British to attack again, but James Abercromby, despite his continued superiority in numbers, rapidly fell back on Lake Saint-Sacrement, abandoning part of his train.

This French victory delayed the British invasion of Canada up the Richelieu River valley by a year. Returning to Quebec City, Montcalm was promoted to lieutenant general. The British government held Abercromby responsible for the humiliating defeat, and he never participated in another British military campaign.

In Canada, and especially in Quebec, the Battle of Carillon has become the symbol of French resistance to the British during the Seven Years’ War. Memories of this battle faded after the conquest of New France, but it drew renewed popular interest in the 19th century, when it was commemorated in a poem by Octave Crémazie, entitled Le Drapeau de Carillon. In 1948, the government of Maurice Duplessis adopted the official flag of Quebec, inspired in part by a religious banner that was said to have flown at the Battle of Carillon.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom