In 1755, the British built Fort William Henry on the shores of Lake George in the northeast of the Province of New York. The fort was a short distance from the border of New France and stood as a threat to Fort Carillon. In August 1757, the French army led by Louis-Joseph, the Marquis de Montcalm, besieged the fort. A few days into the siege, the British, commanded by George Monro, were forced to surrender. In the hours following the surrender, Indigenous warriors allied to the French attacked the British garrison. This has gone down in history as the “Fort William Henry Massacre.”

Background

With the Seven Years' War raging on once again between France and Great Britain, the 1757 campaign was looking promising for the French in America. To begin with, they had just received reinforcements and supplies from France in the spring. In addition, French victories in 1755 at the Battle of the Monongahela and in 1756 at the Battle of Fort Oswego gave France the upper hand. In 1757, Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial, governor of New France, aimed to besiege Fort William Henry on the shores of Lake George (known as Lac Saint-Sacrement by the French). The fort was considered a threat to Fort Carillon.

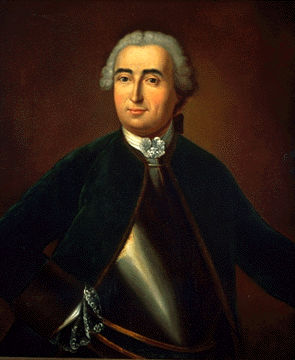

In July 1757, Louis-Joseph, the Marquis de Montcalm, led French troops toward Lake George. More than 8,000 men marched toward Ford Carillon to join this campaign. Some 1,800 were Indigenous “domiciliés” ― allies from the St. Lawrence Valley or the Pays d'en Haut (Up country). (See Seven Nations.) This number turned out to be one of the most significant contingents of Indigenous warriors to join a military expedition during the war. (See Indigenous-French Relations.) As for the remainder of the men, they were made up of soldiers and officers from the land troops and the Troupes de la Marine, as well as Canadian militias. (See also Militia Captain.)

European-style Siege

The march from Fort Carillon began on 29 July for the detachment led by François-Gaston de Lévis, commander of the vanguard, which advanced by land. The troops commanded by the Marquis de Montcalm left on 1 August and sailed through Lake George. Both detachments converged on 2 August around Fort William Henry. As early as the next day, the army’s deployment and siege preparations began.

The fort's garrison, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Monro of the 35th Regiment of Foot, numbered some 2,300 people, excluding women, children, Britain's Indigenous allies and servants. A part of the garrison was within the walls of the fort, while the rest was entrenched in a nearby camp.

On 3 August, the Marquis de Montcalm requested that his British counterpart, Lieutenant-Colonel Monro, surrender. But the latter, who had become more confident following the arrival of reinforcements, responded that he did not fear the French army. At this point, a European-style siege of the fort began. Although pounded by cannons from the fort, French troops started digging trenches as early as 4 August. Two days later, a first French artillery battery pounded the fort, followed a day later by a second battery.

British Garrison Surrenders

On 7 August, the Marquis de Montcalm rushed his aide-de-camp, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, to hand a letter to Lieutenant Colonel George Monro. The letter was from the latter's superior, Daniel Webb. It had been intercepted a few days before by Indigenous allies. In it, Webb advised Monro to surrender.

On the morning of 9 August, the fort hoisted a white flag and requested to surrender. By the end of the morning, the terms of the surrender had been discussed and then signed. Among the articles of the surrender agreement, it was agreed that a French army detachment would escort the British with their belongings to the neighbouring Fort Edward. In addition, the soldiers were to refrain from fighting against the French army and its allies for 18 months. All French, Canadian and Indigenous prisoners captured since the beginning of the war must also be released within three months. The terms of the agreement were advantageous for the victors and generous for the vanquished.

A Parallel War for Indigenous Peoples

Although some Indigenous nations were allied with the French, their war operated in parallel to that of the Europeans. Indigenous peoples’ objectives did not run counter to those of the French but they had their own set of priorities. (See Indigenous-French Relations.) For them, victory meant four things: taking captives, collecting hairs or “scalps,” seizing material (three things that symbolized their participation in the military campaign) and losing as few men as possible.

In the afternoon of 9 August, some Indigenous allies looted and harassed the British wounded and sick in the fort.

Early on the morning of 10 August, a handful of Indigenous allies went to the fort’s makeshift hospital. There, they attacked the British wounded or sick. At the same time, another group of these Indigenous allies went to the neighbouring cemetery. They dug up bodies of those who had died from their wounds or smallpox, mainly to collect scalps.

A few moments later, several allies witnessed the withdrawal of the defeated garrison. The escorting French detachment, which had been agreed upon per the terms of the surrender, was not large enough to hold back the allies’ curiosity. The latter tried to seize luggage or clothes from British soldiers. British officers ordered their troops to abandon their possessions to the Indigenous allies. However, the lack of resistance encouraged the allies to attack the defeated garrison. Alerted by the fleeing British, French and Canadian officers, interpreters and missionaries tried in vain to stop their allies.

The outcome was some 50 dead and more than 500 taken captive. The Marquis de Montcalm bought back some of these captives on the spot, while Governor Vaudreuil did the same a few days later in Montreal. It is estimated that fewer than 100 British were captured, tortured or enslaved by the Indigenous allies.

By the end of 10 August, the allies had withdrawn from the shores of Lake George to return to Montreal or the Pays d'en Haut (Up country), marking the end of their military campaign. They carried with them prestigious tokens of their bravery.

The French army brought down the walls of Fort William Henry to ensure that the enemy would not use it to launch attacks on New France. By the time they withdrew on 15 August, the fort, which had been built barely two years before, was in ruins.

Consequences

The events of 9 and 10 August 1757 had diplomatic and geopolitical consequences. But most significantly, these events had demographic fallouts. In the months that ensued, the British refused to honour the terms of the surrender, blaming the French for not having respected them in the first place. Moreover, the destruction of Fort William Henry temporarily slowed the march of the British army toward Canada. But as early as 1758, James Abercromby stopped by the site while en route to attack Fort Carillon. Finally, the British captives taken to allied Indigenous nations contributed to spreading the contagious smallpox virus. Weakened, these nations were unable to muster warriors for the 1758 and 1759 campaigns. This contributed to Britain gaining a decisive upper hand from 1758 onward during the Seven Years' War. (See The Conquest.)

The memorialization process of the events at Fort William Henry began days after the attack on the British garrison. British authorities ordered that a sensationalist account of the events be published in colonial newspapers. This fueled the fear of Indigenous allies while nurturing a spirit of revenge. In addition, it inspired James Fenimore Cooper's novel The Last of the Mohicans published in 1826, as well as several film adaptations.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom