The birchbark canoe was the principal means of water transportation for Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands, and later voyageurs, who used it extensively in the fur trade in Canada. Light and maneuverable, birchbark canoes were perfectly adapted to summer travel through the network of shallow streams, ponds, lakes and swift rivers of the Canadian Shield. As the fur trade declined in the 19th century, the canoe became more of a recreational vehicle. Though most canoes are no longer constructed of birchbark, its enduring historical legacy and its popularity as a pleasure craft have made it a Canadian cultural icon.

History

Canoes were a necessity for northern Algonquian peoples like the Innu (Montagnais-Naskapi), Ojibwe, Wolastoqiyik ( Maliseet) and Algonquin. After sustained contact with Europeans, voyageurs used birchbark canoes to explore and trade in the interior of the country, and to connect fur trade supply lines with central posts, notably Montreal.

Samuel de Champlain noted the canoe’s elegance and speed, and remarked that it was “the only craft suitable” for navigation in Canada. Artist and author Edwin Tappan Adney, who dedicated much of his life to the preservation of traditional canoe-making techniques, claimed that European boats were “clumsy” and “utterly useless;” and therefore, the birchbark canoe was so superior that it was adopted almost without exception in Canada. As such, most European explorers navigating inland Canada for the first time did so in birchbark canoes.

Construction

Birchbark was an ideal material for canoe construction, being smooth, hard, light, resilient and waterproof. Compared to other trees, the bark of the birch provided a superior construction material, as its grain wrapped around the tree rather than travelling the length of it, allowing the bark to be more expertly shaped. Birch trees were found almost everywhere across Canada, but where necessary, particularly west of the Rocky Mountains in the western Subarctic, spruce bark or cedar planks had to be substituted.

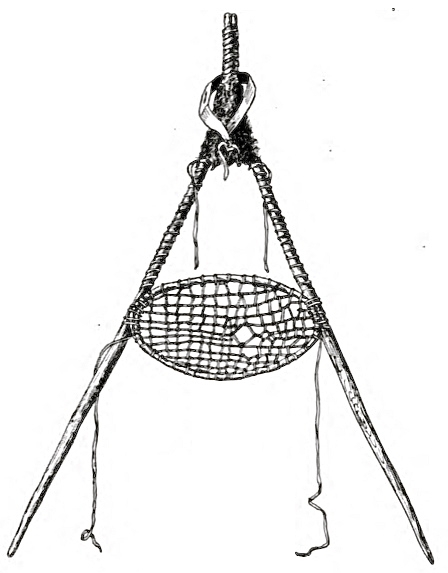

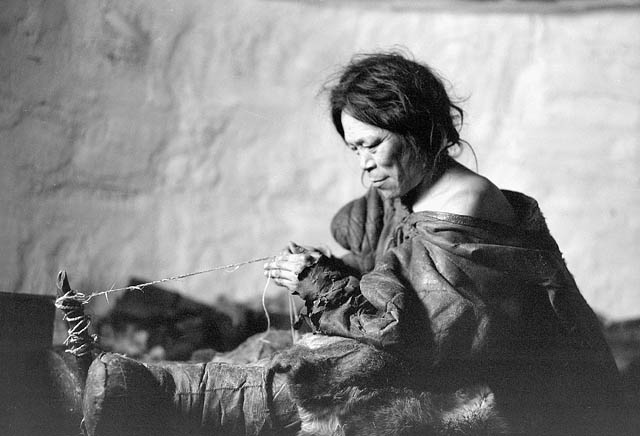

The skills required to build birchbark canoes were passed on through generations of master builders. The frames were usually of cedar, soaked in water and bent to the shape of the canoe. The joints were sewn with spruce or white pine roots, which were pulled up, split and boiled by Indigenous women. The seams were waterproofed with hot spruce or pine resin gathered and applied with a stick; during travel, paddlers re-applied resin almost daily to keep the canoe watertight. Canoes were often painted on the prow, depicting colours, drawings or company insignia. The shape of each canoe differed according to its intended use, as well as the traditions of the people who made it.

As the fur trade grew, increasing demand meant Indigenous producers could no longer supply all the canoes needed. Around 1750, the French set up a factory at Trois-Rivières.

Types of Canoes and Routes

The types of birchbark canoes used by Indigenous peoples and voyageurs differed according to which route it was intended to take and how much cargo it was intended to carry.

The famous canot du maître, on which the fur trade depended, was up to 12 m long, carried a crew of six to 12 and a load of 2,300 kg on the route from Montreal to Lake Superior . Past Lake Superior, the smaller canot du nord carried a crew of five or six and a cargo of 1,360 kg over the smaller lakes, rivers and streams of the Northwest. The canoes were propelled by narrow paddles with quick, continuous strokes, averaging 40–45 per minute.

The avant (bowsman) carried a larger paddle for maneuvering in rapids and the gouvernail (helmsman) stood in the stern. A canoe could manage 7 to 9 km per hour, and a special express canoe, carrying a large crew and little freight, could cover longer distances in typical 18 hour days.

Cultural Legacy

The canoe is a cultural mainstay in Canada. Its image is used as a symbol of national identity in countless iterations. For example, the 1935 Canadian silver dollar’s reverse image, designed by Emanuel Hahn, depicts a voyageur and Indigenous person canoeing together in front of a windswept jack pine, under the northern lights, with a cargo of Hudson’s Bay Company furs. The canoe is also featured in the Québécois folk story La Chasse-galerie, and is a popular choice for designers and marketers wishing to evoke a sense of Canadian identity.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom