Filmmaking is a powerful form of cultural and artistic expression, as well as a highly profitable commercial enterprise. From a practical standpoint, filmmaking is a business involving large sums of money and a complex division of labour. This labour is involved, roughly speaking, in three sectors: production, distribution and exhibition. The history of the Canadian film industry has been one of sporadic achievement accomplished in isolation against great odds. Canadian cinema has existed within an environment where access to capital for production, to the marketplace for distribution and to theatres for exhibition has been extremely difficult. The Canadian film industry, particularly in English Canada, has struggled against the Hollywood entertainment monopoly for the attention of an audience that remains largely indifferent toward the domestic industry. The major distribution and exhibition outlets in Canada have been owned and controlled by foreign interests. The lack of domestic production throughout much of the industry’s history can only be understood against this economic backdrop.

This article is one of four that surveys the history of the film industry in Canada. The entire series includes: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938; Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973; Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present; Canadian Film History: Notable Films and Filmmakers 1980 to Present.

The Tax Shelter Era, 1974–82

The federal government proved reluctant to exert control over the distribution and exhibition of films in Canada. But it did act decisively to provide financial incentives for investment in domestic film production through tax benefits. In 1974, it increased the Capital Cost Allowance (CCA) from 60 to 100 per cent. This created a tax shelter that allowed investors to deduct from their taxable income 100 per cent of their investment in Canadian feature films. This resulted in a massive increase in Canadian production and marked the beginning of the “tax shelter era.”

For a film to qualify as Canadian, it had to be at least 75 minutes long. At least one producer and two-thirds of the “above the line” creative team had to be Canadian. And at least 75 per cent of the production and post-production services had to be completed in Canada. The tax shelter approach echoed the conclusion of the Tompkins Report, issued by the secretary of state in 1976. Since American control of Canada’s theatrical marketplace made it virtually impossible for Canadian films to turn a profit domestically, the Canadian film industry should focus instead on producing commercial products for export. ( See also: Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973.)

A new aggressiveness took hold within the industry. Priorities shifted from the low-budget, cultural film to higher-budget, commercial projects. This policy shift came under scrutiny after the critic Robert Fulford (writing under the name Marshall Delaney) wrote a scathing review of David Cronenberg’s CFDC-funded horror film Shivers in the September 1975 edition of Saturday Night magazine. The review, titled “You Should Know How Bad This Film Is. After All, You Paid For It,” declared, “If using public money to produce films like this is the only way that English Canada can have a film industry, then perhaps English Canada should not have a film industry.” A furious debate was sparked in the House of Commons over the use of tax-payer dollars to fund films.

Ironically, the beginning of this period was marked by the success of two films of high quality with solid cultural pedigrees: Ted Kotcheff’s The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974), starring Richard Dreyfuss and based on Mordecai Richler’s novel; and Ján Kadár's Lies My Father Told Me (1975), based on a script by Ted Allen. Both films were commercial hits and received Oscar nominations for their screenplays. But the quality of these films proved to be the exception during this period and not the rule. Most of the international co-productions and trite commercial vehicles that littered the second half of the 1970s — such as City on Fire (1979) with Henry Fonda and Ava Gardner, Running (1979) with Michael Douglas, and Nothing Personal (1980) with Donald Sutherland and Suzanne Somers — provided one box office and artistic embarrassment after another.

Some benefits did emerge from the tax shelter era. The increase in production provided valuable experience to a growing industry of craftspeople. A number of prominent producers, including Harold Greenberg, Garth Drabinsky, Robert Lantos and Don Carmody, emerged as Canada’s leading movie moguls. David Cronenberg credited his tax-shelter films — Shivers (1975), Rabid (1977), Fast Company (1979), The Brood (1979) and Scanners (1981) — with launching his career, though he also recognized the overall scheme as a failure.

A number of tax-shelter films did very well at the box office: the queer cinema classic Outrageous! (1977); Daryl Duke’s critically-acclaimed The Silent Partner (1978), starring Elliot Gould and Christopher Plummer; Ivan Reitman’s Meatballs (1979) with Bill Murray; Bob Clark’s Murder by Decree (1979) with Plummer, Donald Sutherland and Geneviève Bujold; Paul Lynch’s Prom Night (1980) with Jamie Lee Curtis; Peter Medak’s The Changeling (1980) with George C. Scott; Louis Malle’s Oscar-nominated Atlantic City (1980) with Burt Lancaster; Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Quest for Fire (1982); and perhaps most notoriously, Clark’s Porky’s (1981), which stood for decades as the top-grossing Canadian film of all time.

A handful of films produced during this period managed to project a distinctly Canadian sensibility. These included Silvio Narizzano’s Why Shoot the Teacher (1977) and Allan King’s Who Has Seen the Wind (1977). Both films were adapted from Canadian novels. Gilles Carle’s Les Plouffe (1981), Francis Mankiewicz’s Les bons débarras (1980) and Phillip Borsos’s impressive debut feature The Grey Fox (1982) are widely considered among the best Canadian films ever made.

The tax shelter incentive did result in a boom in Canadian film production. Seventy-seven feature films, with an average budget of $2.5 million, were produced in Canada in 1979. In 1974 there were only three. However, many of the films did not receive distribution. Many that did were practically indistinguishable from poorly made American films. In 1982, the CCA was reduced to 50 percent and the era came to an end.

The Quebec Cinema Act, 1983

The tax shelter succeeded in stimulating commercial activity in English Canada’s film industry. But it had a very different impact on the film industry in Quebec. The limited market for French-language films in North America provided investors with no incentive to invest in them. As Manjunath Pendakur has explained, “In 1978 and 1979, two-thirds of the films made in Quebec were produced without benefit of the tax shelter. Film directors who in the 1960s helped put Canada on the world map — such as Claude Jutra, Gilles Carle, Michel Brault, Denys Arcand — were unable to get financing to make any French-language films.” Only three per cent of feature films produced in Canada from 1978 to 1981 were in French.

In 1981, the Parti Québécois came to power under René Lévesque. The preservation of Québécois culture, particularly through preserving the French language, was a key part of its mandate. The government commissioned a study of the film industry in Quebec — Le cinéma: une question de survie et d’excellence. This led to legislation in the form of Bill 109. Introduced in December 1982, Bill 109 was a bombshell with regards to film distribution. In addition to creating several new regulatory bodies, the bill required distribution companies in Quebec to be at least 80 per cent Canadian-owned. Distributors and exhibitors were also required to contribute a percentage of their profits to a production fund.

The bill was unanimously adopted in June 1983. However, the ratification process was protested and delayed at every opportunity by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and its president, Jack Valenti. The provincial Liberal Party came to power in December 1985. In October 1986, Minister of Cultural Affairs Lise Bacon signed an agreement with the MPAA that actually strengthened the Hollywood majors’ position and legalized their presence in the province. (See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969.)

The Film Products Importation Bill, 1988

A similar situation transpired at the federal level a year later. In 1987, the federal government under Brian Mulroney attempted to address the long-standing problems faced by Canadian distribution companies. Minister of Communications Flora MacDonald introduced the Film Products Importation Bill. If passed into law, it would have allowed the Hollywood majors to distribute in Canada any films for which they owned world rights or in whose production they had participated. Canadian companies would have had the right to distribute all other movies.

The proposal generated intense lobbying in both Ottawa and Washington. It encountered stiff opposition from MPAA President Valenti. He enlisted US President Ronald Regan to speak out against the bill. When the Film Products Importation Act was tabled in May 1988, the original proposals had been considerably weakened. During the free trade negotiations that followed, the federal government agreed to abandon even those.

CFDC Becomes Telefilm Canada

In the early 1980s, the film industry in Canada was on shaky ground. It was almost wholly dependent upon government financing and unable to secure screen time in Canadian theatres. Francis Fox, the Liberal federal minister of communications, issued the National Film and Video Policy in 1984.The CFDC was transformed into Telefilm Canada and given a $35-million Broadcast Program Development Fund. This reflected its new dual orientation: funding television programs as well as theatrical feature films.

Further initiatives were taken to assist in the marketing and promotion of English Canadian feature films, an area always perceived as the industry’s Achilles heel. The failure of the Quebec Cinema Act and the Film Products Importation Bill were monumental missed opportunities. In 1986, Telefilm created the Feature Film Fund. In 1998, the organization increased the Broadcast Fund to $60 million and created the Feature Film Distribution Fund. This introduced lines of credit for Canadian companies to draw from to distribute films internationally.

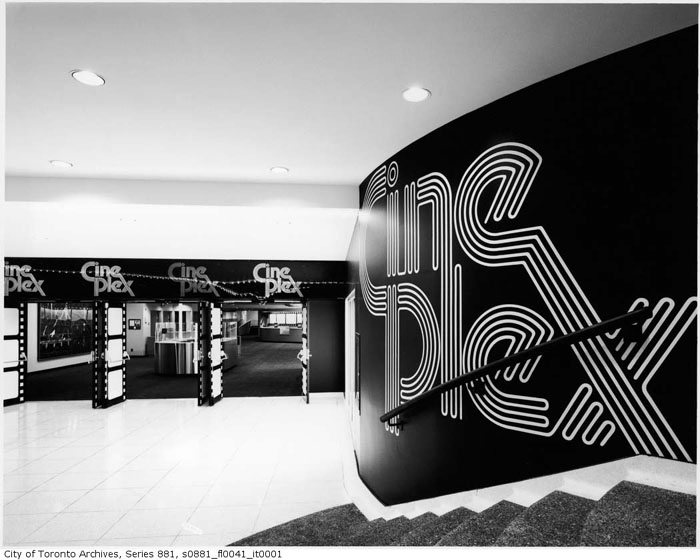

Famous Players and Cineplex Odeon — Sales and Mergers

In 1994, the federal government approved the takeover of the Canadian assets of Paramount Communications by Viacom of New York. These assets included the Canadian Famous Players theatre chain. In turn, Viacom promised to exhibit more Canadian films. It also pledged to spend more money on the marketing of Canadian films in Famous Players theatres. In 1998, the chain of US and Canadian Cineplex Odeon theatres was bought by Sony. In 2002, Onex Corporation, a Canadian holding company, acquired Loews Cineplex from Sony. It sold off Loews, the American parent, but kept the Canadian theatres.

In 2003, Cineplex Odeon merged with Galaxy Entertainment to create Cineplex Galaxy. In 2004, Cineplex Galaxy acquired Famous Players from Viacom. This effectively brought an end to a legendary Canadian business rivalry dating back 60 years. The new company, known simply as Cineplex Entertainment, came to control 60 per cent of the movie screens in Canada. The Federal Competition Bureau required that Cineplex divest itself of 34 theatres from British Columbia to Ontario. Halifax-based Empire Theatres bought 27 of them and became Canada's second-largest exhibitor. American-owned AMC, which merged with Loews in the US, became the third largest.

Funding Cuts and Telefilm Canada Mandates

In the mid-1990s, funding cuts at all levels of government began to take their toll on the industry. This severely affected the support offered by the provincial funding agencies. In 1995, the Liberal government under Jean Chrétien cut Telefilm’s budget from $123 million to $109.7 million. The NFB’s budget was reduced by $4 million and the CBC’s by $44 million. In 1996, Mike Harris’s Conservative government in Ontario slashed funding to the Ontario Film Development Corporation (OFDC) and the Ontario Arts Council. The OFDC was virtually scuttled. It lost funding for production and marketing but retained the Ontario Film Investment Program.

In 1998, Heritage Minister Sheila Copps announced the creation of a new feature film fund. It came into effect in 2001. Under the direction of new Telefilm Canada head Richard Stursberg, the goal of the $100-million-a-year fund was to boost the audience for Canadian films. Noting that Canadian films typically account for only two per cent of annual box-office revenue, Stursberg set a target of reaching five per cent in five years. The result was a series of middling generic films that strove for popular appeal. These included Paul Gross’s Men with Brooms (2002), William Phillips’s Foolproof (2003), Charles Martin Smith’s The Snow Walker (2003) and Émile Gaudreault’s Mambo Italiano (2003). The difficult nature of predicting the box-office success of a film was perhaps exemplified by My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002). The Toronto-shot film, written by and starring Winnipeg-native Nia Vardalos, was denied funding by Telefilm. It went on to gross more than $240 million at the box office.

In 2005, Telefilm’s report cited that box-office share for domestic films in Quebec was a remarkable 21.2 per cent. However, English Canadian films languished at 1.6 per cent. This was only a fraction higher than when the Ontario provincial treasurer complained 80 years earlier that “not one per cent of the pictures shown in Canada are Canadian made.” (See also: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938.) Also in 2005, Sarah Polley and Don McKellar lobbied the federal government to change the way it supports Canadian films. They recommended that theatres be forced to devote more screen time to Canadian films and their trailers, and that broadcasters be required to air Canadian films and their advertisements. No such action was taken.

Rising Populism

Despite the failure of Telefilm’s box office mandate, a new sense of populism seemed to take hold. Many filmmakers began producing movies with broader commercial appeal that still retained a specific sense of Canadian identity. Michael Dowse followed his indie head-banger hit FUBAR (2002) with the raucous electronica extravaganza It's All Gone Pete Tong (2005), the equally successful FUBAR 2 (2010), the hit hockey film Goon (2010) and the Daniel Radcliffe vehicle What If (2013, a.k.a. The F Word).

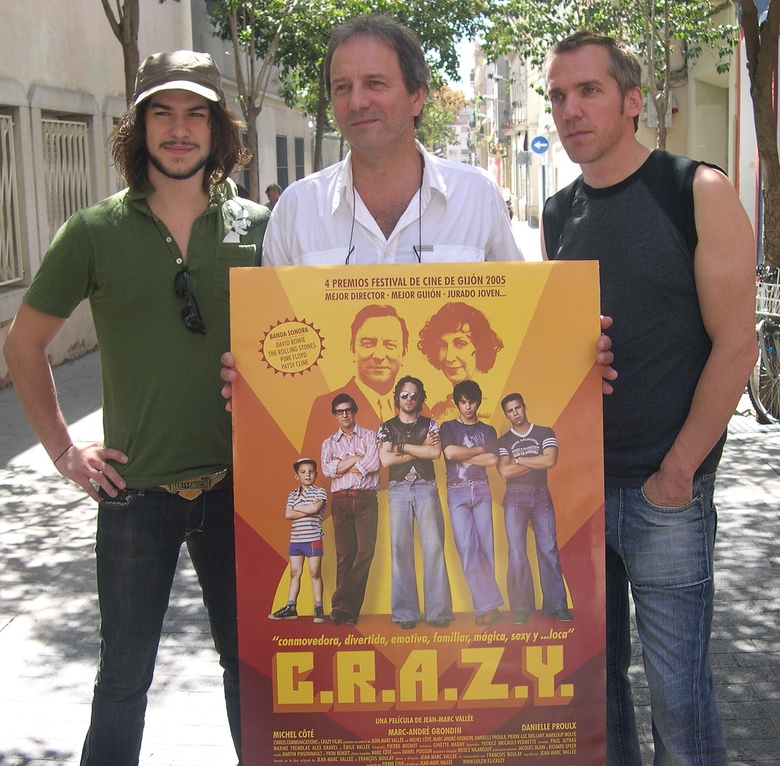

Quebec continued its string of box office successes with Charles Binamé’s biopic The Rocket (2005), starring Roy Dupuis as Maurice Richard, Jean-Marc Vallee’s inspired coming-of-age story C.R.A.Z.Y. (2005) and Erik Canuel’s bicultural buddy movie Bon Cop Bad Cop (2006). The Rocket and La grande seduction screenwriter Ken Scott had a huge hit in Quebec with the whimsical Starbuck (2011) — remade by Scott in Hollywood as the Vince Vaughn vehicle Delivery Man (2013) — while English Canada looked to model that same success with Don McKellar’s remake of The Grand Seduction (2013).

The cult comedy Trailer Park Boys: The Movie (2006) scored a rare success in English Canada. It opened on more than 200 screens and grossed $1.3 million on its opening weekend. It was followed by the sequel, Trailer Park Boys: Countdown to Liquor Day (2009), which went on to gross more than $3 million. (See also: Trailer Park Boys.) The indie youth sex comedy Young People F—ing (2006) received an unexpected boost in publicity when it became the poster child for the proposed changes to the Income Tax Act (Bill C-10). The act would have allowed the heritage minister or a government committee to retroactively deny tax credits to films that were deemed offensive and “contrary to public policy.”

Actor Sarah Polley made a distinguished directorial debut with the beautifully crafted, Oscar-nominated Away from Her (2006). She followed that success with two other investigations of infidelity: the colourful and moving Take This Waltz (2010); and the inventive personal documentary Stories We Tell (2012). Rubba Nada made an impressive debut with Sabah (2005) and had a modest hit with Cairo Time (2009). Paul Gross made a valiant attempt at a historical prestige piece with the lavishly-produced First World War drama Passchendaele (2008). Kari Skogland adapted The Stone Angel (2007) from the novel by Margaret Laurence. Michael McGowan had a sleeper hit with the cross-Canada road movie One Week (2008), starring Joshua Jackson. Jacob Tierney wrote and directed a successful star vehicle for Jay Baruchel with The Trotsky (2009). And Cube’s Vincenzo Natali scored another sci-fi hit with Splice (2010).

In 2011, Telefilm announced a new system to measure the success of Canadian films. It takes into account the sales of a film’s worldwide rights and gives points based on film festival appearances and awards. It also factors in the amount of private investment a film generates. In 2013, a group led by Robert Lantos that included David Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, Paul Gross and former Alliance CEO Victor Loewy attempted to launch Starlight, a television channel devoted to Canadian movies. However, the proposed channel died when it was denied mandatory distribution by the CRTC.

Notable Recent Successes

The 1990s and first decade of the 21st century saw the production of world-class cinema in Canada. The industry as a whole has become a multi-billion-dollar business built over 50 years. Many American film and television productions are shot here. They take advantage of the professional crews, state-of-the-art studio space and infrastructure, tax breaks and generally lower dollar. Despite the massive difficulties still faced in the exhibition market, the industry is on reasonably solid footing. In the 1960s, no more than two or three Canadian films a year received proper distribution in the Toronto market. In 2011, more than 50 Canadian movies played the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto is now the largest market in the world for English Canadian films.

In 1997, Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter won the Grand Jury Prize, the International Critics Prize and the Ecumenical Award at the Cannes Film Festival. This made it the most honoured Canadian film ever to play the festival. It was nominated for Academy Awards for adapted screenplay and best director — the first for a Canadian director. In 2001, Zacharias Kunuk’s Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner) won the Caméra D'Or at Cannes. The film was the first dramatic feature to be shot entirely in Inuktitut with an all-Inuit cast. In 2004, Denys Arcand’s Les Invasions barbares/The Barbarian Invasions (2003) won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film — another first for a Canadian. Four Canadian films in the next eight years earned Oscar nominations in the same category: Deepa Mehta’s Water (2006); Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies (2010); Philippe Falardeau’s Monsieur Lazhar (2011); and Kim Nguyen’s Rebelle (War Witch) (2012).

In 2006, the comedy Bon Cop Bad Cop grossed nearly $12 million, making it the most successful Canadian film at the domestic box office to date. In 2010, Resident Evil: Afterlife 3D, a co-production with Germany, became the top-grossing Canadian film of all time. It surpassed Porky's with a worldwide box office of $250 million.

David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence (2005) and Eastern Promises (2007) are, of his long career, his most successful at the box office. He is also internationally recognized as one of the top directors in the world. Other Canadian directors have become sought-after commodities in Hollywood. Atom Egoyan (Chloe, 2009; Devil’s Knot, 2013), Philippe Falardeau (The Good Lie, 2014; Chuck, 2016), Jean-Marc Vallée (The Young Victoria, 2009; Dallas Buyer’s Club, 2013; Wild, 2014; Demolition, 2015; Big Little Lies, 2017–; Sharp Objects, 2018) and Denis Villeneuve (Prisoners, 2013; Sicario, 2015; Arrival, 2016; Blade Runner 2049, 2017; Dune, 202) all directed big-name Hollywood stars in high-profile American productions. Villeneuve is perhaps the most notable of this group. He earned an Academy Award nomination for directing the acclaimed Arrival. He secured his status as a preeminent science fiction filmmaker by following that success with Blade Runner 2049 and an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune.

In recent years, Xavier Dolan has quickly gained a reputation as the most talented Canadian filmmaker, with his first autobiographical feature film J’ai tué ma mère (2009; I Killed My Mother). This first success is followed by a sensual and cinematic feature film Les amours imaginaires (2010; Heartbeats), as well as by Laurence Anyways (2012) and Tom à la ferme (2013; Tom at the Farm).

It is now possible to speak of a Canadian film industry as a whole, with a thriving domestic industry in Quebec. However, feature films made by English-speaking Canadians remain the weak link in the chain. Government money continues to be crucial to their success. The bond between English Canada’s feature filmmakers and their Canadian audiences remains a tenuous one at best.

See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969; Quebec Film History: 1970 to 1989; Quebec Film History: 1990 to Present; 30 Key Events in Canadian Film History; Exhibit Eh: Canadian Film History in 10 Easy Steps; Documentary Film; Canadian Film Animation; Experimental Film; Film Distribution; Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time; National Film Board of Canada; Telefilm Canada; Film Education; Film Festivals; Film Censorship; Cinémathèque Québécoise; The Craft of Motion Picture Making.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom