A debt is something that one owes to another. While debt can take many forms, the term usually refers to money owed. In a Canadian context, debts have become an increasing concern during the past three decades. According to Statistics Canada, at the end of the second quarter of 2020, Canadian non-financial businesses, governments and households owed almost $7.1 trillion in debts. That works out to roughly $186,000 per person. (See also Public Debt.)

Debt has had a bad reputation throughout much of history. The various factors that have forged this reputation include defaults (failure to pay debts) by most national governments at some point, debtors’ prisons and cautions by writers such as William Shakespeare. Islam forbids charging interest on debts.

Debt financing (raising money by selling debt instruments like bonds) is a crucial tool of war. Governments borrow money from their citizens to pay for military and defence activities. Borrowing capacity was likely a determining factor in conflicts ranging from the Napoleonic Wars to the First and Second World Wars to, more recently, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In Canada, the federal government launched the Victory Loans program for this purpose during the two world wars. (See also Canada and the War in Afghanistan.)

Debt in Accounting

For accounting purposes, a debt results from a past transaction that creates an obligation with a knowable cash value. Debts commonly appear on the right side of companies’ balance sheets. Balance sheets are typically structured using the equation:

Assets = Liabilities (or Debts) + Owners Equity (or Capital).

See also Assets in Canada; Capital in Canada.

Advantages of Debt

In the consumer and business sectors, debt no longer has strictly negative associations. A far more nuanced view has emerged. This process began in the early 20th century, as loan financing became a key tool in stimulating the automotive, real estate and other sectors. In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes revolutionized economics when he suggested that governments could ease the impact of slowdowns and recessions by borrowing money and spending it. Keynes argued that the resulting economic activity would begin a cycle that would stimulate future growth. This growth would in turn ease the burden of debt from government spending. (See also Keynesian Economics in Canada.)

Consumer Debt

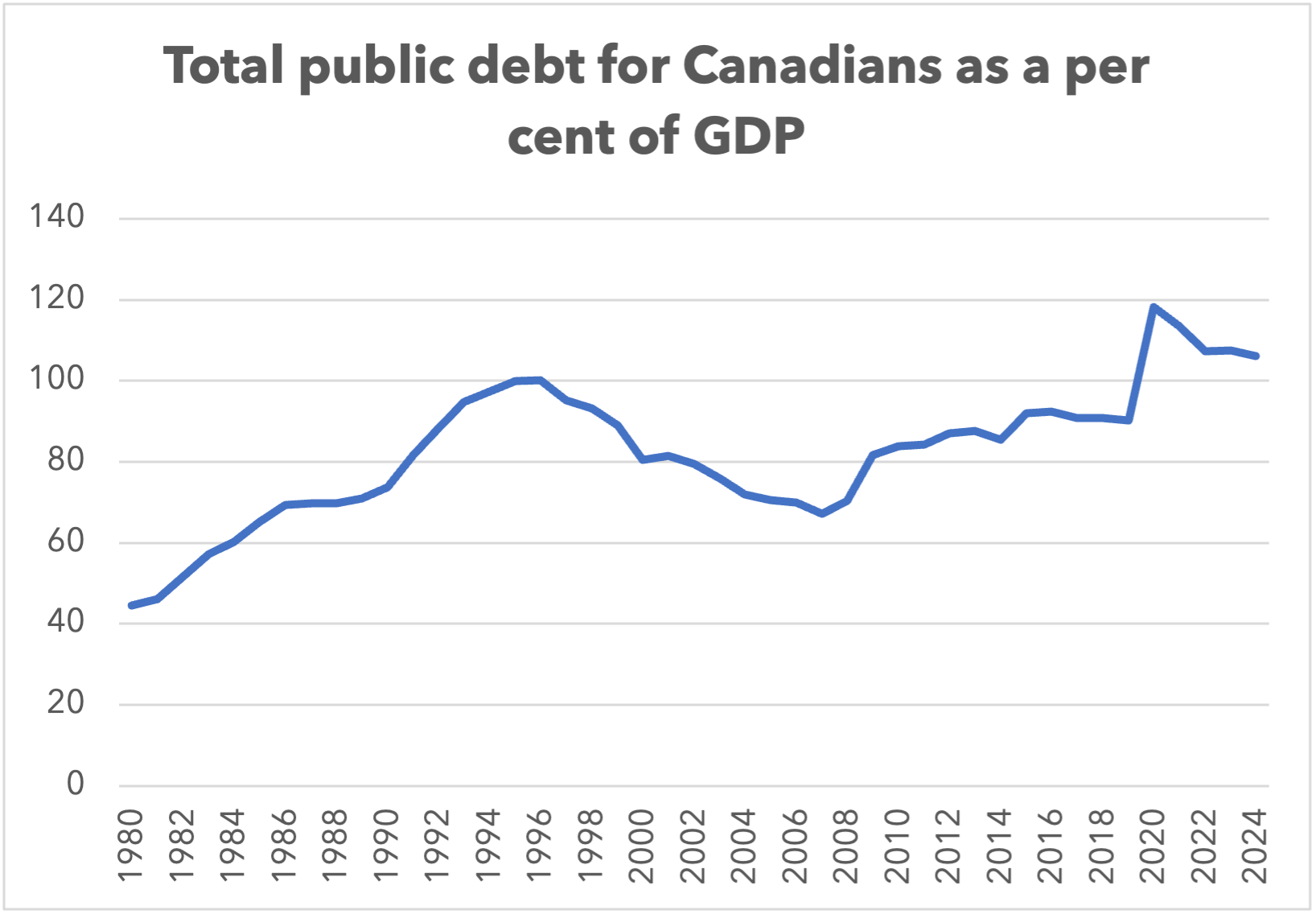

In recent years, there has been growing concern about debt accumulation in Canada, particularly at the consumer level. High consumer debt is in part the result of heavy mortgage burdens. Debt as a percentage of household income hovered at near-record highs in the late 2010s, surpassing 170%. Were a recession to hit, many households faced the risk of falling short on their debt payments.

This prospect became real during the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. However, emergency government aid and mortgage payment-deferral programs from banks helped many Canadians continue to finance their obligations. The debt-to-income ratio actually fell by more than 15 percentage points in the second quarter of 2020. When government support ends and as courts reopen, however, many households may face insolvencies and bankruptcies.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom