Public debt is any financial liability held by a government. Governments undertake these debts in any period when their spending exceeds their revenues. To make up the difference — or deficit — they will sell IOUs to the general public. These IOUs — or bonds — oblige the government to repay the loan with interest. In Canada, financial borrowing is a regular part of fiscal policy at the federal and provincial levels. Municipalities, however, are constitutionally bound to balance their budgets. They can only take on long-term debt for capital projects.

Origins of Public Debt

Some governments in classical antiquity, such as the Greek city states and the Roman Empire, borrowed from civilians on a limited basis. Cash-strapped sovereigns would sometimes do the same during Europe’s medieval period, especially in times of war.

In the early modern era, the cost of warfare increased substantially. European governments began to borrow from their increasingly wealthy merchant and banking classes. In some cases, the public debt generated major political problems. Sovereigns often defaulted on their debts, sending their creditors into financial crisis. Such defaults also weakened the sovereign in the long run, resulting in higher interest rates to compensate for the risk.

Over time, states became more committed to repayment. Legal institutions evolved to protect creditors from default. These conditions, in turn, could generate fiscal crises for governments — especially if they were unable to unilaterally mint new coinage or raise taxes. For instance, in the early 17th century, England’s King Charles I sought to raise taxes to repay his government’s debts. To do so, he was required to call a parliament (which represented only aristocrats at the time). When parliament rejected Charles’s tax hike, he shut it down and ruled alone. This conflict over who would bear the cost of repayment led to the English Civil War (1642–51). The same basic sequence of events occurred in Paris a century and a half later, leading to the French Revolution (1787–99).

European governments and their colonies gradually learned to manage their debts in ways that both ensured repayment and empowered central governments to raise taxes. The lending of funds was increasingly mediated and even conducted by central banks. Many banks followed the model of the Bank of England, founded in 1694. Scholars have noted that this generated a symbiotic relationship between governments and private finance. Governments benefit from increased flexibility and fiscal capacity. Private financial institutions, meanwhile, retain large amounts of public bonds. These are typically low-risk and highly tradable.

Public Debt in the 20th Century

In global terms, the de-risking of public debt has been uneven. Fiscal crises have still happened in certain circumstances throughout the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. Following both World Wars, financial liabilities had to be carefully managed and often renegotiated. Financial managers did not always succeed. For instance, the failure to renegotiate Germany’s liabilities to foreign governments led to major economic crises in 1923 and 1931.

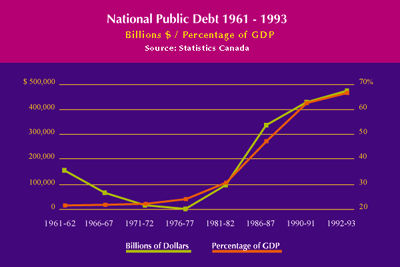

In 1867, Canada's debt was $94 million. It grew slowly until 1915, when the First World War pushed the figure to $2.4 billion. During the Great Depression, the debt rose to $5 billion. By the end of the Second World War, it had reached $18 billion.

Sovereign debts were more stable after the Second World War. But governments in the global north came under strain in the 1970s. Many of them saw their trade balances decline sharply. This was partly because of the sudden spike in oil prices in 1973. It was also partly because governments tried to sustain fixed exchange rates. This made their manufactured goods more expensive on foreign markets.

As money flowed outward, governments’ revenues declined. Their budgets then bumped up against major constraints. As a result, New York City suffered a major fiscal crisis in April 1975. It had to be bailed out by New York State. Britain suffered a sudden fiscal crisis the following year. It had to be rescued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In both cases, creditors pushed the debtor governments to introduce significant austerity measures. They also had to roll back some of the progressive welfare programs they had created over previous decades.

The next period of substantial increase in government debt occurred in the 1980s. Net federal debt increased from $84.7 billion in 1981 to $239.9 billion in 1986. By 1996, it had reached $569.7 billion.

The High-Interest Period of the 1980s

Fiscal crises were an even broader global problem during the high-interest period of the 1980s. Canadian governments’ finances were strained at the time. But they were never at serious risk of default. Nonetheless, this period shaped the political conversation around public debt in ways that persist today.

Three mechanisms created the unique economic conditions of the 1980s. First, beginning in 1979, the US Federal Reserve Board started an aggressive policy of raising interest rates on public bonds. By 1981, they had pushed the prime rate as high as 21.5 per cent. This policy was rooted in the theory that the ongoing problem of inflation was driven by excess demand. However, later empirical studies suggest that the inflation of the 1970s was driven more by “cost-push” dynamics than “demand-pull” ones. Specifically, the rising price of oil — needed to produce many commodities — increased costs for manufacturers. They then passed on those costs through higher commodity prices. (See also Commodity Trading.)

Second, the higher interest rates on public bonds led to higher interest rates on virtually all other loans in the US economy. When interest rates are raised on public bonds, it puts financial pressure on banks to raise interest rates on both their assets and their liabilities. If interest rates on deposits are low while rates on public bonds are high, savers will be incentivized to withdraw their deposits and purchase bonds. Private banks could then be highly destabilized. At the same time, as banks pay out higher interest on deposits, they must also charge even higher interest on loans to make a profit. Hence, the escalation of the interest rate on public bonds leads to an escalation of interest rates throughout the economy.

Third, the higher interest rates on public bonds in the United States led to higher interest rates around the world. This occurred due to different competitive pressures. If Canadian bonds, for instance, had sustained their low interest rates, they would have been sold off in exchange for higher-yield American securities. In the process, investors would have to sell off huge quantities of Canadian dollars. This would make the value of the Canadian dollar decline substantially, thus increasing the price of imports. To avoid a major fall in the value of the currency, the Bank of Canada and dozens of other central banks around the world followed the Federal Reserve and raised interest rates.

High interest rates had several far-reaching effects. In the global north, economic growth slowed, unemployment rose and mainstream attitudes toward public debt soured. As interest payments drained government budgets, conservative politicians increasingly argued that they could not afford social programs. (Interest payments on the debt in Canada took about 23 per cent of the federal budget in 1993.) However, conservative politicians have also typically advocated tax cuts. As a result, their record of reducing deficits is rather weak. In fact, the most successful consolidations of government debt in North America after the 1980s were made under Bill Clinton in the US and Jean Chrétien in Canada. They were both politically centrist.

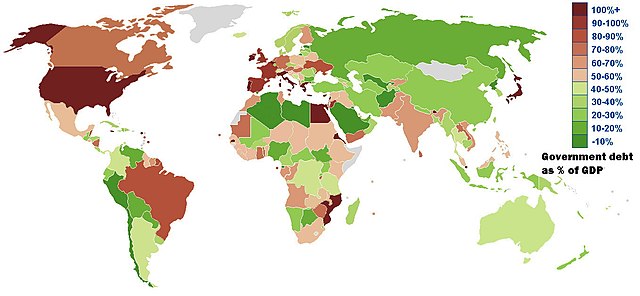

In the global south, high interest rates also slowed growth. The high cost of borrowing stymied the process of industrialization and development. Several governments were highly burdened by interest payments. They had to default on their debts or renegotiate them. In some cases, as governments’ credit ratings declined, they could not find domestic creditors. Instead, they had to borrow from foreign creditors in US dollars. Such loans are risky because they are often issued with higher interest rates. If the borrowing government’s currency falls relative to the US dollar, that government could be unable to raise money for repayment. Governments in the global south requiring bailouts from the IMF were on numerous occasions subject to “structural adjustment programs.” These mandated severe cuts to government spending.

In certain cases, fiscal crises can also lead directly to periods of high inflation. This can happen when states in the midst of a fiscal crisis put pressure on their central banks to print money and thus “inflate away” their debts. Similarly, when governments are desperate to obtain foreign currency, they may also devalue their currencies to make their goods cheaper in foreign markets.

A more complex dynamic can also occur, however, when concern about repayment provokes a sell-off of a country’s public bonds and its currency. The currency loses value. Foreign goods then become more expensive. In turn, businesses and consumers may ask for larger loans from banks. In cases where the debtor country has a weak manufacturing or export sector, there can be little to prevent the currency from falling further. If the market is dominated by foreign goods whose prices remain stable in foreign currency (like the US dollar) while the domestic currency is depreciating, then everyone will have an incentive to sell their domestic currency for US dollars. In turn, a spiral of currency devaluation and domestic inflation can emerge.

For example, Zimbabwe’s hyperinflationary episode from 2007 to 2009 exemplifies these trends. There was both a devaluation-inflation spiral and targeted attempts by the central bank to inflate away government debts. As a result, Zimbabwe’s currency collapsed. The country then switched to US dollars and a dollar-denominated currency. Zimbabwe did not bring back its own currency as the sole legal tender until 2019. It was replaced by the ZiG (Zimbabwe Gold) currency in 2024.

Following the global recession of 2008–09, various countries in the global north became squeezed yet again, notably Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain. Greece in particular needed aid from the European Central Bank and the IMF. They gave bailouts to Greece in 2010, 2012 and 2013. But Greece had to accept many harsh and deeply unpopular austerity policies in exchange for the aid.

Public Debt and GDP

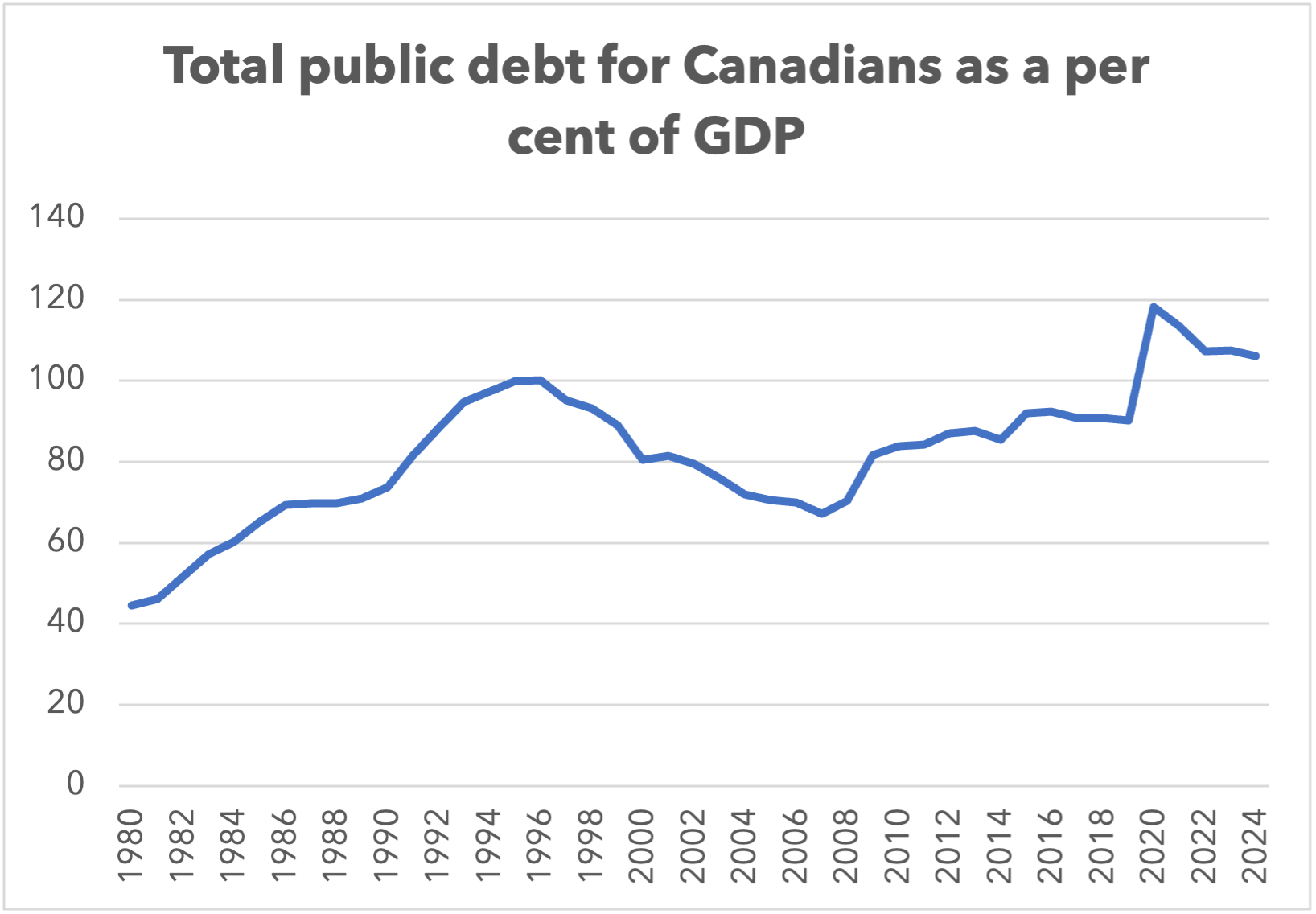

As a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the federal “debt ratio” grew from 23.8 per cent in 1981 to 47.4 per cent in 1986 and 71.4 per cent in 1996. Interest payments on public debt rose concomitant with the increase in debt, reaching $47.8 billion in 1996. This was about 27 per cent of total federal spending, compared to only 15.9 per cent in 1981. This increase led to the perception that the government was on a debt treadmill, borrowing to service past debt and worsening the deficit problem.

The 1980s were also notable for the substantial increase in debt of subnational governments. In 1981, the net debt of provincial, territorial and municipal governments stood at $29.4 billion, or 8.2 per cent of GDP. In 1995, the net debt stood at $208.9 billion, or 26.9 per cent of GDP. As a proportion of GDP, the public debt was larger at the end of this period than it had been since 1947.

Debates on Public Debt

As we have seen above, public debt comes with costs and risks. Debtor governments must restrain their spending to repay creditors. In high-interest periods, these payments can become quite onerous. If an unforeseen crisis causes tax revenues to plummet, repayment can be difficult. Fiscal crises grant creditors a unique form of power within the state, which undermines its sovereignty.

Economists have long debated whether the increase in public debt is a significant problem. In one view, the public debt is funds we owe to ourselves, so choosing to pay for government spending later rather than sooner is not a cause for concern. But transfers

between taxpayers and bondholders in the future may have significant and unintended consequences for the distribution of income.

Proponents of non-interventionist or “small government” fiscal approaches have criticized deficit spending on grounds that are not always accurate. Here, we briefly address five arguments advanced by “deficit hawks.”

First, deficit hawks often argue that government deficits saddle future generations with a crushing burden of debt. But, as economist Thomas Piketty has argued, societies in the global north have only grown wealthier over time. It is therefore more informative to think of the public debt as distributional rather than generational. In other words, we must ask who bears the burden of taxation (which finances interest and repayment) and who holds public bonds?

Second, deficit hawks often refer to a growing public debt as “unsustainable.” As we have seen, governments’ borrowing capacity can hit a limit, at which point they are likely to experience a crisis. But economists have not yet determined a hard and fast formula for determining that limit in advance. In the 1990s, European governments laid the basis for a monetary union by signing the Maastricht Treaty. It stipulates that their public debts as a percentage of GDP should not exceed 60 per cent. But as of 2024, EU governments reached 81.6 per cent. By contrast to earlier periods, economists are somewhat less worried about this scenario. This is partly due to the growing evidence that the austerity policies following the 2008–09 global financial crisis were harmful to recovery.

Third, neoclassical economists typically argue that deficit spending is inherently inflationary. This is because it increases the money supply — the sum of liquid money relative to the goods and services in the economy. But as we have seen above, in countries like Zimbabwe, public debt can play a role in spurring an inflationary crisis. This is especially true where industry is weak, imports are high and debt is paid in foreign currencies. However, this scenario is rare. Recent studies show that on average, there is no significant relationship between the money supply and inflation. This is likely because increased demand usually spurs higher production rather than price increases.

Fourth, the motivation for deficit spending can sometimes be mislabelled. Deficit hawks often argue that when governments spend beyond their means, they are merely currying favour with the public. Certainly, there is some truth in this. But the argument deserves to be qualified in two ways. On the one hand, currying favour with the public is a benign and even essential part of democratically responsive governance. (See also Parliamentary Democracy in Canada.) On the other hand, deficit spending often grows as a natural response to slumps in the business cycle. If commercial markets contract, a government’s social spending is likely to grow. At the same time, slumps cause governments to collect less in tax revenue. Thus, consumer spending has a “pro-cyclical” pattern. It rises and falls with economic growth. Meanwhile, government deficits generally have a “counter-cyclical” pattern. They rise and fall inversely with economic growth, softening the impact of recessions.

Fifth, deficit hawks have argued that when governments borrow money, it takes from a limited pool of loanable funds that would otherwise be invested in production. Careful studies indicate that there is relatively little evidence of this. Any growth-diminishing effects are offset by the deficit’s boost to demand. Relatedly, neoclassical economists have also suggested that the burden of public debt could have growth-inhibiting effects. But careful analysis has found this dynamic to be quite minor.

Public Debt in Canada

Public debt has been a source of anxiety for centuries. Writing in the 1700s, Adam Smith predicted that “the enormous debts… at present oppress, and will in the long run probably ruin, all the great nations of Europe.” Experience has shown that public debt is less ruinous than he believed. But it does come with some risks for countries with a weak industrial base, weak tax collection and heavy reliance on foreign creditors.

These issues do not pose any immediate crisis for Canada. Public debt in Canada reached a low point of 53.1 per cent of GDP in 2007–08. It then climbed to 76.2 per cent by 2023–24 in response to the post-2008 recession.

Rather, in Canada, public debt is a distributional concern. As noted above, the distributional impact of interest payments is likely to be progressive if the tax system is progressive and public bonds are owned by institutions like unions’ pension funds. On the other hand, it will be regressive if taxes fall disproportionately on low-income people and bonds are owned by the wealthy. Data on bond ownership in Canada is limited. But it is fair to assume that government bonds are, like all other financial assets, overwhelmingly owned by those in the wealthiest 10 — and especially 1 — per cent of the population.

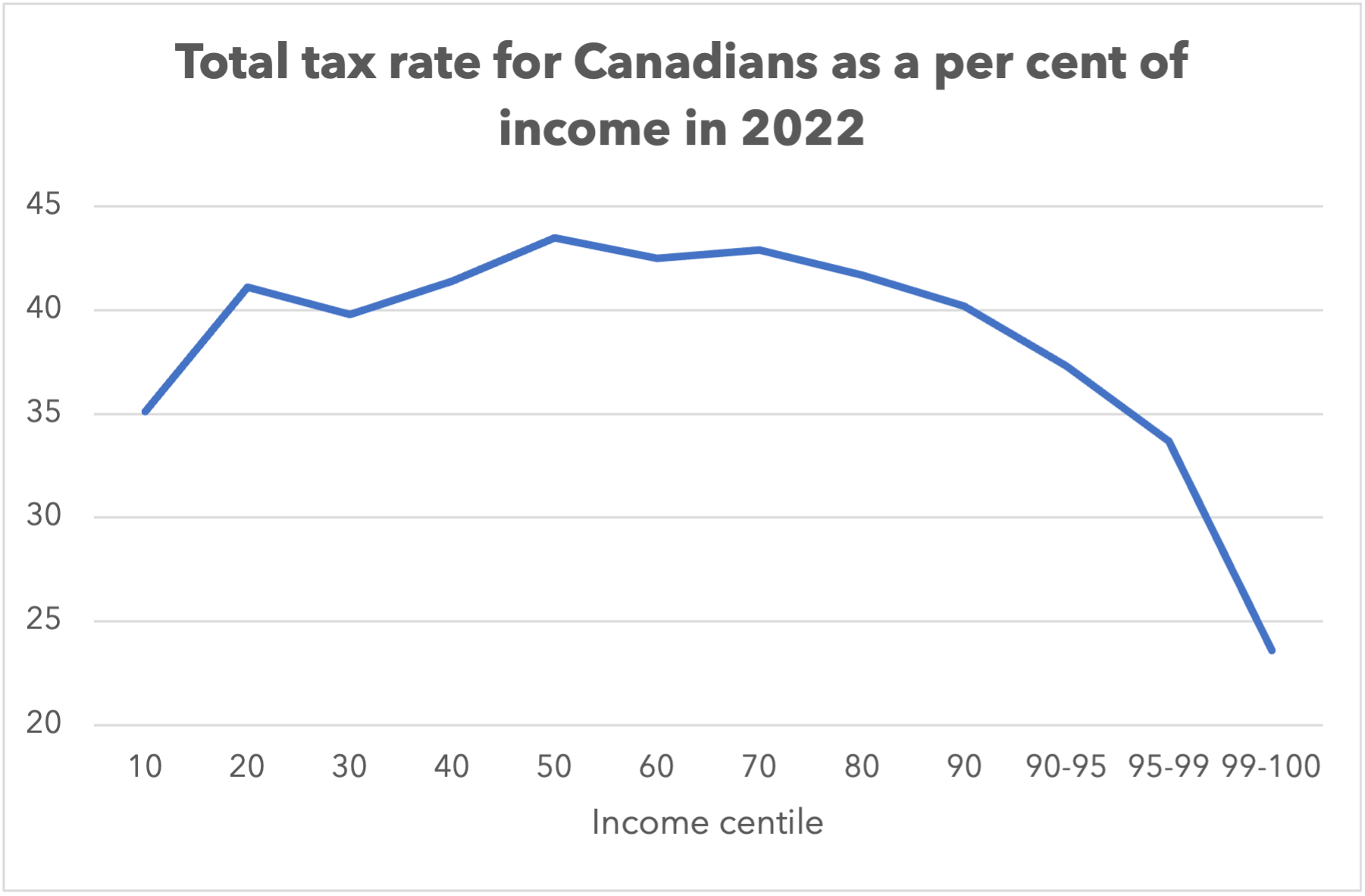

On the other side of the equation, the distribution of the tax burden overall is a cause for concern. A 2024 report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives shows that the overall debt burden is only mildly progressive in the bottom 70 per cent of income earners. But in the top 30 per cent it is actually regressive. This means the top 1 per cent of income earners actually pay the lowest rate of tax on average. This results from Canada’s reliance on regressive taxes such as sales tax and property tax. It is also due to the comparatively low weight of progressive taxes like income tax. These facts combined suggest that the distributional effect of interest payments on public debt is likely to be regressive. At the same time, however, those interest payments are just one component of a broader system.

Another key problem for Canada is the question of which governments have the right to issue debt. As noted above, Canada’s federal and provincial governments are allowed to run deficits, but municipalities can only do so with restrictions. As a result, municipalities in Canada are more fiscally constrained than in most other countries in the global north. Municipalities are also responsible for managing much of Canada’s frontline social services and public infrastructure. But the constraint on borrowing means that they often rely on transfer payments from the higher levels of government. As researchers at the Federation of Canadian Municipalities have observed, this constitutional order hobbles municipal capacity for infrastructure development. It also generates persistent tensions between the levels of government.

(See also Monetary Policy; Public Expenditure; Debt in Canada; Public Finance.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom