The Duplessis orphans were a cohort of children placed, from 1935 to 1964, in nurseries, orphanages and psychiatric hospitals, where many of them were mistreated or abused. A significant number of these children were falsely diagnosed as being mentally defective, to enable the institutions housing them to receive subsidies allocated to psychiatric facilities. This practice primarily occurred under Premier Maurice Duplessis, whose name has therefore been used to designate these children. Following a number of years of legal battles and political pressure, most of the Duplessis orphans have obtained a measure of compensation from the Quebec state.

This article contains sensitive material such as physical and sexual abuse that may not be suitable for all audiences.

Sociopolitical Background

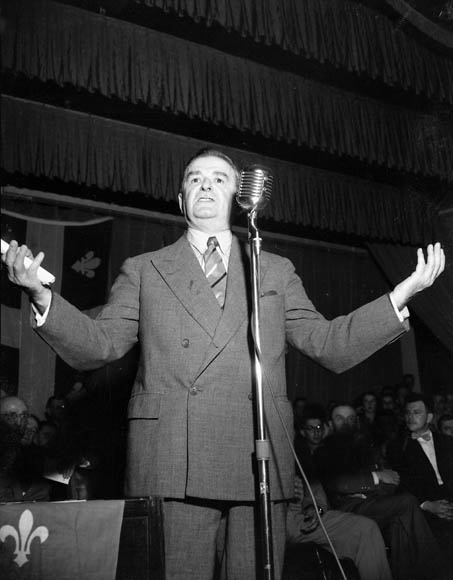

In 1948, the federal government introduced a subsidy program with respect to provincial health services. At that time, the Premier of Quebec, Maurice Duplessis, instead advocated that institutions managed by religious communities be funded by private sources. His primary concern was federal interference in their activities. Nevertheless, the federal funding of hospitals and private care institutions increased substantially in Quebec during this period.

From 1935 to 1964, thousands of orphaned children were abandoned (sometimes because they were born out of wedlock) or entrusted to the State by a parent or other members of their family. These orphans were raised in facilities like nurseries, orphanages or psychiatric hospitals run by Catholic congregations.

In 1999, researcher Martin Poirier and Professor Léo-Paul Lauzon maintained that the institutionalization of some children beginning in the 1950s may have been done for financial reasons. They showed that, in 1956, the federal government allocated a subsidy of $0.70 per day for every child living in an orphanage, while allocating $2.25 for every patient diagnosed with a mental illness and confined in a psychiatric institution. These investigators demonstrated that falsely diagnosing some orphans with mental disorders enabled some Quebec institutions to receive these larger subsidies from the federal government.

Abuse and Consequences

The children confined in these institutions received basic care; the discipline was harsh and some were neglected, molested or abused. Many were subjected to severe physical violence by the religious staff or by their guardians, who sometimes used leather straps or wooden rods. Those who were falsely diagnosed with an intellectual disability were medicated. Some even underwent electroshock treatment.

The children subjected to abusive treatment in these institutions had no opportunity for healthy development. The level of education they were given was largely inadequate. They did not have the support of a normal family and could not easily take up a career. Many saw their mental health profoundly affected.

The awareness of this phenomenon began with the publication of autobiographies such as the Les fous crient au secours (1961) and Ma chienne de vie (1964). These autobiographies exposed the situation of patients in the asylums. The Rapport de la Commission d’étude des hôpitaux psychiatriques submitted to the Government of Quebec in 1962 helped bring an end to this practice of committing children to psychiatric hospitals.

The children who left the institutions were not equipped to live in the outside world. They disappeared from public awareness for approximately twenty years. Their story resurfaced in 1991, with the publication of Les enfants de Duplessis by Pauline Gill (1991). This led to the publication of many other stories and accounts that laid bare the experiences of these children.

Legal Proceedings

In 1992, Hervé Bertrand and other individuals institutionalized during their childhood as orphans began the process, with attorney support, of initiating a class action lawsuit. They were able to meet with dozens of people who had been institutionalized during their childhood, to paint a picture of the events and experiences common to these orphans.

In 1993, seven requests for permission to launch a class action lawsuit were submitted to the Court of Quebec. The prospect of class actions was initially a source of hope; however, a judgment rejected the requests in 1995, stating that they did not meet the criteria required for class actions. Moreover, the initiative was not supported by the Quebec Class Action Fund and most of the orphans did not have the means to fund these legal proceedings on their own. The charges for which they were seeking redress included the erroneous placement of orphans in psychiatric hospitals and the lack of adequate education. Although they did not deny placing children in institutions, the religious congregations noted the problems with the lack of personnel and money with which they were dealing at the time. They did, however, dispute the accusations of abuse and attempted to prevent them from devaluing all of the work done by the religious congregations throughout Quebec history.

Meanwhile, the Montreal police suggested to some of the orphans that they file formal complaints regarding acts of a criminal nature. The file was transferred to the Québec Provincial Police, as the seven institutions involved were located in different regions. At times, some of the complainants found the investigation intimidating, disrespectful or misleading. Following the assessment of the 321 complaints lodged by the orphans, Paul Bégin, the Attorney General of Quebec, decided not to proceed. This decision was explained by a lack of evidence, statutes of limitation, the withdrawal of some complaints, and the fact that some of the accused had died.

Formal Apologies and Compensation

The Ombudsman, Daniel Jacoby, did, however, agree to the request by the representatives of the orphans to investigate the case. In January 1997, he filed a report recommending that the orphans receive, at the very least, a public apology from the parties involved and suggested compensation scenarios to be funded by the Quebec state, the medical profession and the religious congregations.

In November 1997, the federal Minister of Justice, Anne McLellan, mandated the Law Commission of Canada to assess “the measures to redress physical and sexual abuse of children in institutions… managed, funded or sponsored by the government.” A study conducted in 1997 compared the quality of life and mental health of a group of Duplessis orphans with those of another group of low-income individuals who participated in a study conducted in 1988. The findings showed the potential for long-term negative effects of the institutionalization on the children. The Duplessis orphan group had a significantly lower level of education, more marked attachment difficulties, a lower degree of well-being and a higher level of stress.

In March 1999, the Government of Quebec, under Lucien Bouchard, made a public apology to the Duplessis orphans. A $300,000 grant was paid to the Duplessis Orphans Committee. A $3-million fund to assist approximately 3,000 victims was also created, but no compensation was awarded on an individual basis. Further, the Quebec bishops refused to apologize and dismissed the idea of paying financial compensation.

In the spring of 2000, the Comité d’appui pour la justice aux orphelins de Duplessis obtained the support of public figures, including former PQ Health Minister Denis Lazure and some members of the medical profession, to reopen the debate regarding compensation for the formerly institutionalized children. On 30 June 2001, the Duplessis Orphans Committee accepted the government’s offer of compensation. Under the National Reconciliation Program for Duplessis Orphans, this offer provided for $10,000 per person, in addition to a further $1,000 per year of confinement, up to a maximum of $25,000. Any individuals who accepted such compensation were required to waive any further actions regarding the damages covered under this program.

Subsequent to 2001, more than 1,000 Duplessis orphans have thus shared compensation totalling approximately $26 million. In 2007, a new Quebec government program provided that an additional 1,270 orphans committed to non-psychiatric institutions would receive $15,000 each. In total, the Quebec government received more than 6,500 requests for financial assistance from Duplessis orphans. Although it did not offer a formal apology, the Collège des médecins did express its regrets in a letter sent to the orphans in 2012.

In March 2018, some of the orphans filed a class action suit for $875,000 each against 8 religious communities. However, the suit was rejected by the Superior Court of Quebec. Two other class action suits were filed in April 2018 and July 2020.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom