Two elections within 12 months. Two leaders fighting for supremacy: one intellectual and cold, the other deliberately vague and hiding his ambition. In 1925, and again in 1926, Conservative Arthur Meighen took on Liberal William Lyon Mackenzie King. The outcome was the King-Byng affair and a conclusion that would shape Canadian politics for the remainder of the 20th Century.

1920s Tariff Debate

In memory, the 1920s were boom years, the flappers of the Jazz Age riding in convertibles with their beaus. But Canada was not uniformly prosperous, farmers and labourers struggled, and party leaders talked incessantly about trade and tariffs as the way to improve Canadians' lot. Meighen's Conservatives were for a high tariff, a popular policy with Ontario and Québec manufacturers. King favoured some reduced tariffs, someday soon — his way of appealing to the West. There, angry farmers had formed their own party, the Progressives, who won 64 seats in the 1921 election, 14 more than the Conservatives, producing Canada's first minority government. The King government had spent four years cautiously trying to woo the Progressives and simultaneously trying to retain its complete stranglehold on Québec. The election of 29 October 1925 would show how well the Grits had done.

There were no opinion polls in the 1920s, no reliable way of measuring the public's views of parties and leaders. Nor was there radio or television, or chartered aircraft to fly leaders back and forth across Canada without cease. Instead there were a few forays into the hinterland by railway and automobile and constant efforts to get the partisan press to trumpet the party line. The leaders obviously mattered, but few Canadians got to see them.

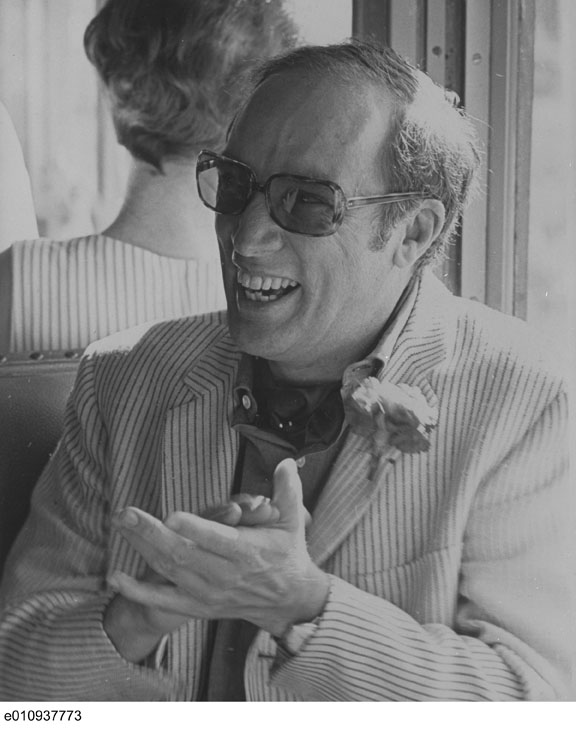

As the late October election drew near, King believed his government had done well, advancing Canada's interests in the world, increasing autonomy within the British Empire, and giving sound government. He offered Canada more of the same — a "common sense tariff" — and good relations between English and French Canada. It's not what you did that mattered most, King wrote often in his private diary, it's what you prevented. What King had prevented was the icy, sarcastic Meighen from being in power. That meant high tariffs and, he believed, trouble with Québec.

Meighen Takes Ontario

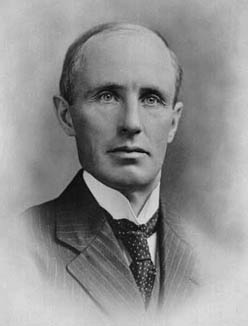

Cold he might have been, but Arthur Meighen was no slouch as Tory leader. He could beat King in debates in the House of Commons day in and day out, his rapier thrusts of oratorical genius making the Prime Minister's platitudes look ridiculous. Meighen also spent weeks outside Parliament organizing the Conservatives, rebuilding his party in Québec, where the memory of conscription in the Great War was fresh. He worked hard in the Maritimes and Ontario, but his principles, his belief in high tariffs, made the Prairies tough territory. In 1921, he had no luck there at all; could he do better this time?

In fact, Meighen did win seven Manitoba and three Alberta seats, against 20 Prairie seats for the Liberals and 24 Progressives. In Québec, Meighen's months of work won him only four seats, while King had the rest. But the shocker was in Ontario, where Meighen garnered 68 of 82 ridings, and in the Maritimes, where he won 23. With 10 seats in British Columbia, the Tories had a total of 116, while King had 99 and the Progressives 24. Even more striking, Meighen took 46.5 per cent of the popular vote, well ahead of King's 40 per cent. It was a Tory minority, a triumph for Meighen.

Constitutional Tussle

Or was it? As was his right, King declined to turn over power to the Tories. He would meet the House and let Parliament decide who should govern. Meanwhile, he would try to accept as many of the Progressives' demands as possible. Once the session opened, he even struck a Cabinet committee to talk regularly with the Progressives' leaders.

King looked as if he might survive — until a scandal blew up in the Customs Department. King had kept the Progressives on side by supporting the establishment of Old Age Pensions and by lowering taxes, but the scandal, investigated by a parliamentary committee, directly implicated two successive Customs ministers. Facing defeat on a motion of censure (a “no-confidence” vote in the House), King went to the Governor General, Viscount Byng, to seek a new election. He had governed successfully for nine months, he said, and he was entitled to a dissolution of Parliament. Byng disagreed and gave Meighen the chance to govern. King promptly resigned his seat and told Parliament there was no longer a prime minister. The next day, Arthur Meighen and the Tories had the reins.

Under the rules of that era, ministers named to Cabinet had to resign their seats and be re-elected in a by-election. Instead of adjourning Parliament, the too-eager Meighen played just as fast and loose with the rules as King had — he gave up his own seat but appointed Conservatives as only "acting ministers." With King fuming in Parliament's public galleries, Liberals argued that if the acting ministers were legally running their departments, they must vacate their seats; if they did not hold office legally, they had no right to govern. This did the trick with the Progressive MPs, and Meighen lost the confidence of the House. He then received the dissolution Byng had refused King. The election was called for 14 September 1926.

Appeal to Nationalism

Meighen ran, as before, on a high tariff, all the while attacking Liberal corruption and maladministration. King ought to have been on the defensive, his lackluster government having done little. But the shrewdest politician in our history could see that fortune had dropped a constitutional issue into his lap: the interference by a British Governor General with the rights of Canadians to govern themselves. In his diary on 2 July he wrote: "I could not believe [Byng] would deliver himself so completely into my hands.” Later, he noted that the "great issue [...] that the people will respond to [...] is the making of our nation."

So it proved. King did not attack Byng directly; that might upset some people. But there was much tsk-tsking at how Meighen had tried to govern illegally, the implicit sub-text being that he had done so with the aid of the Governor General. Initially convinced that this was spurious, Meighen found himself forced to respond and obliged to confront the rising nationalism King unleashed. The "King-Byng Wing-ding" was underway.

In truth, the election was about who was to rule: King or Meighen? Meighen was the abler man, a better speaker, a fine organizer with the courage of his principles. There was no hidden agenda there. King was a master of fuzzy platitudes driven by the winds of opinion and as responsive as a pillow to the last person to sit on him. With a choice like that, there could be no doubt: Canadians would have King. He reassured them, while Arthur Meighen threatened them.

The result of the election was clear, even if the popular vote was almost evenly divided. King's Liberals took 125 seats (including nine Liberal-Progressives who agreed to help King form a majority coalition) to the Tories 91. Meighen won only one seat on the Prairies and four in Québec. The 20th Century would belong to King and his Liberal Party.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom