"Canada is a hard country to govern," observed John A. Macdonald, Canada's first Prime Minister. It's also a hard country in which to get elected. With a population of vastly differing need and interests, a politician must broker East-West agreement, balance the needs of business and labour, French and English constituents, and a host of other conflicting interests. Liberal Party has been masterful in building political coalitions. Laurier, St Laurent, Pearson, Trudeau and Chrétien have each followed the prescription successfully, but the chief alchemist was William Lyon Mackenzie King. His most dazzling feat was the creation of a coalition government after the Liberals won a bare majority in the election of 1921.

In December of that year, mysterious, coded messages signed "A.H." and addressed to the Prime Minister, piqued the interest of an indiscreet Winnipeg telegraph operator The operator passed these messages on to Dr Rambeau, a veterinarian and disgruntled Liberal. Rambeau identified "A.H." as Andrew Haydon, an emissary of Prime Minister Mackenzie King. Scouring local hotels, Rambeau confronted Haydon at the Fort Gary Hotel. Haydon had been sent to Winnipeg to court the leader of the Progressive Party, T.A. Crerar.

Without Crerar's support, King would not have a majority in the House of Commons. Rambeau, and most of the Eastern Liberals, hated the Progressives, a western protest party that held 64 seats, giving these up-starts the balance of power in the House. King had to structure a Cabinet that would satisfy his powerful Quebec supporters (The Liberals had swept every seat in that province) and yet mollify aggrieved interests throughout the East. T.A. Crerar's Progressives and their 64 seats were a very attractive prize for the Prime Minister.

|

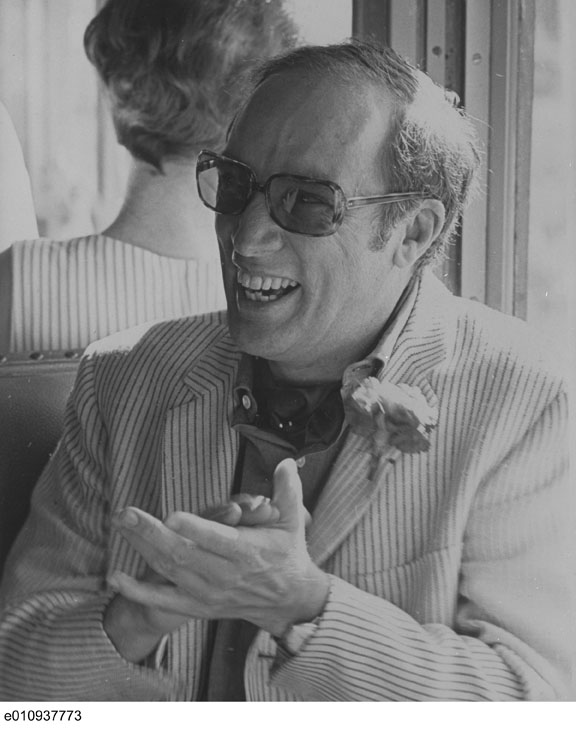

| W.L.M. King during the election campaign of 1926 (courtesy NAC/PA-13886). |

Crerar's dilemma would look familiar to any political observer today. He was disposed to join the government and to use his influence to implement at least some of the Progressive agenda, but his followers objected. The radical Alberta group, in particular, wanted nothing to do with party politics. Fueled by regional discontent and focused on particular issues, the Progressives were ill equipped to deal with King, the master of compromise and chicanery.

King formed his Cabinet. The Progressives stayed out, but their enemies in the East gladly accepted the offices tendered them. Forced by their hatred of the Conservatives to support King when he needed them, the Progressives disintegrated over the next two elections. Enough Progressives returned to the Liberal fold to keep King in power for most of the next 20 years. Another fragment of the Progressive Party formed the Ginger Group, which eventually created the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (later the NDP).

More pertinent to today, after experiencing two devastating election losses, in 1935 and 1940, the Conservative Party sought to renew itself by choosing a Progressive as its leader, adopting that oxymoronic name, Progressive Conservative.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom