Background

Since the 1990s, electoral reform has been increasingly associated with calls for an end to the federal and provincial governments’ use of the first past the post (FPTP) voting system in favour of one that is proportionally representative of Canadians’ political preferences. Reform has been supported by such civil organizations as Fair Vote Canada, Lead Now, the Council of Canadians, the Assembly of First Nations, the Canadian Federation of Students, and others, in addition to the federal Liberal Party, the New Democratic Party and the Green Party. (See also Electoral Systems)

In addition to ensuring that Canadians’ political preferences are reflected in government, electoral reform is considered desirable because of its potential to promote participation from women and cultural minorities. Multiple studies have demonstrated that mixed and proportional electoral systems are associated with stronger representation of women, while majoritarian systems such as Canada’s are associated with relatively weak representation of women.

There is no substantial indication that such alternative electoral systems lead to enhanced representation of cultural minorities. However, some proponents of reform, such as the Law Commission of Canada, have supported legislative changes that would encourage political parties to increase the representation of Indigenous persons and people of colour among their candidates.

Electoral Systems

First Past the Post

Under FPTP, all Members of Parliament (MPs) are elected to represent specific geographical electoral districts (known as ridings). In each riding, the candidate who receives the most votes wins the corresponding seat in Parliament (see Electoral Systems). This system has been in place since the earliest elections under French and British colonial rule. FPTP is simple to understand and is widely acknowledged to produce more majority parliaments and therefore stable government over the long term.

The primary issue that critics of this system highlight is that it often leads to majority governments when the winning party garnered less than a majority of popular votes. In the 2015 federal election, for instance, the Liberal Party won almost 40 per cent of the popular vote, but won 54 per cent of the seats in Parliament. The structure of the FPTP system does not guarantee that the party with the greatest number of popular votes will form the government. This occurred in the 1979 federal election, when the Progressive Conservatives won 35 per cent of the popular vote but formed the government with 48 per cent of the seats in Parliament, while the Liberals won 40 per cent of the popular vote but won fewer seats.

It is often argued that FPTP encourages strategic voting — in which voters attempt to ensure that their ballot is not wasted. This happens when a voter’s preferred candidate has, for instance, a lesser chance of winning in a three-way race. In such cases, voters use their ballot to block their least preferred candidate by voting for a second choice. FPTP can also result in vote-splitting, in which similar parties or candidates take votes from each other — sometimes to the advantage of other candidates.

Alternative Vote or Ranked Ballot

Alternative vote systems (sometimes called ranked ballot voting) involve single-member ridings. Voters rank the candidates on the ballot, one from each party, in order of preference. If a candidate does not win by a majority of first-choice votes, then the candidate with the least first-choice votes is eliminated and the second-choice votes of people who voted for that candidate are distributed among the remaining candidates. This process is repeated until one candidate amasses more than 50 per cent of votes.

It’s argued that in such systems candidates are elected by a true majority of voters and that the impulse towards strategic voting may be diminished along with vote splitting. It’s also thought to reduce negative campaigning since candidates need the support of their rivals’ followers. A criticism of the alternative vote in single member constituencies is that, as a majoritarian system, it can squeeze out smaller parties in favour of larger political parties.

Proportional Representation in Canada

Proportional representation (PR) is a term used to describe any electoral system that is designed to ensure that the share of a party’s representation in the legislature is proportional to the votes that party received in the election. Generally, the idea is that if x per cent of people vote for a party, then that party should receive x per cent of the seats in the legislature. Each variation requires that more than one representative be elected in each riding.

Proportional representation is not itself a voting system; however, there are a number of systems that follow its principles. There are three main variations: party list PR, single transferable vote (STV) and mixed-member proportional (MMP). Options for electoral reform in Canada have generally revolved around STV and MMP.

Each system can be organized in different ways — the following descriptions cover their general composition.

Party List PR

In the party list system, each political party releases a list of its candidates to the public, who in turn vote for a party of their choosing. Depending on the specific system, voters can either have a say in which candidates appear on the party list (called an “open list”), or not (a “closed list”). The number of votes a party receives is equal to the number of candidates elected from that party. In such systems, voters cast their ballot for the party of their choosing and not for specific local candidates.

In this system, used in many countries worldwide, governments are often composed of many political parties. Coalition governments or other forms of multi-party cooperation are therefore necessary if government is to work effectively.

Single Transferable Vote

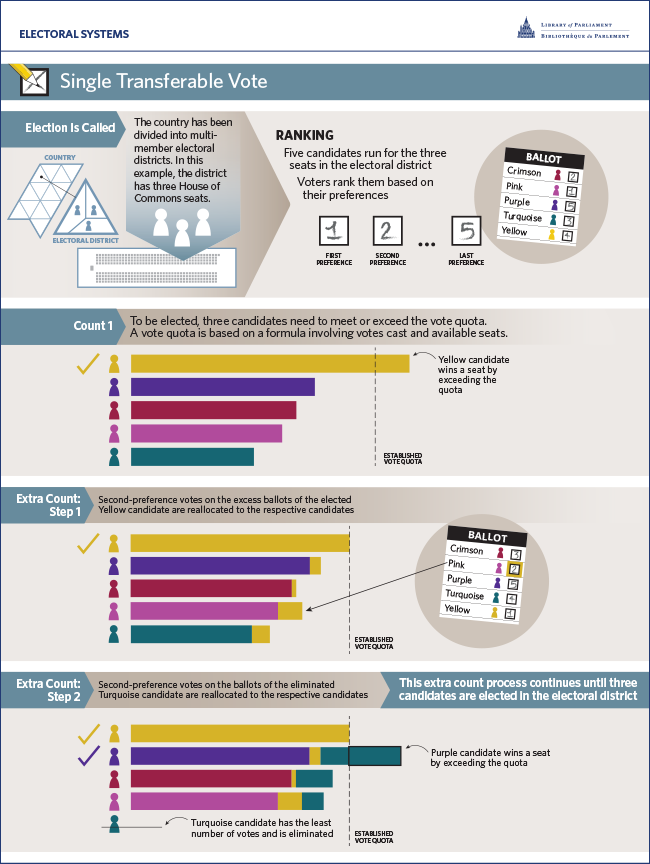

The single transferable vote (STV) involves a system of ranked-ballot voting in which multiple candidates are elected in each riding. Parties can run more than one candidate in each riding. Voters rank the candidates in their district in order of preference. Before the election, a quota, or set number of votes a candidate needs to gain a seat, is established. If a candidate receives more votes than the quota requires, those “surplus votes” are distributed to the second preference of the voters who chose that particular candidate. If there are still seats to fill in that district, the candidate in last place is eliminated, and the second preference of voters who had voted for him or her are distributed accordingly. This process continues until all seats in the district are filled.

Critics have suggested that STV is overly complex and that having multiple representatives in the same riding could lead to political disorder. It is also argued that STV tends to create minority or coalition governments. Proponents of STV argue that is creates more proportional election results and bolsters local representation.

Mixed-Member Proportional

Under MMP, representatives would be elected to represent constituencies on a first past the post basis. However, under most versions of MMP, voters would also be given a second ballot on which they would vote for their preferred party. Therefore, while voters may vote strategically on their first ballot, the second ballot would deliver a comprehensive nationwide popular vote. Once the regional representatives have been elected, an additional group of representatives would be added to the legislature from either a closed or open list to ensure that its composition reflects the popular vote.

With the exception of British Columbia, every province that has taken an active interest in electoral reform has examined MMP as the most viable opportunity. It was endorsed by the 2004 report on electoral reform compiled by the Law Commission of Canada — a comprehensive study of the issue.

Senate Reform in Canada

Discussions of electoral reform in Canada have not been limited to FPTP and its alternatives. An important and related conversation has concerned reform of the Senate.

Since its establishment in 1867, senators have been appointed by the governor general on the advice of the prime minister. (These appointments were initially for life, but senators are now forced to retire at age 75.) Several politicians and commentators have criticized the institution on the basis that it is undemocratic. Polls also suggest that the vast majority of Canadians support some form of Senate change, be it abolition or reform (see Public Opinion). According to a poll released in April 2015, 41 per cent of Canadians believe the Senate should be abolished, while another 45 per cent believe it should be reformed.

Although the NDP, the Liberals and the Conservative Party have all expressed a willingness and desire to reform the Senate, there is little consensus on what that reform would encompass. Under Stephen Harper, the Conservatives supported a transition toward a system in which senators are democratically elected and subject to term limits. The Liberal Party supports a system in which senators are not connected to the political parties themselves, but are suggested for appointment by officials outside of the Prime Minister’s Office. To demonstrate his commitment to such reform, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau ejected all 32 of the Liberal senators from his caucus in January 2014. As prime minister, Trudeau appointed 22 independent senators selected by an advisory board, in 2016. The NDP, on the other hand, supports the complete abolition of the Senate.

The actual process of Senate reform is complex. According to the Supreme Court of Canada, a constitutional amendment to alter the Senate would demand agreement from the House of Commons, the Senate and seven or more of the provinces, representing at least 50 per cent of Canada’s population. Complete abolition of the Senate would demand the agreement of all of the provinces.

Federal Electoral Reform

The move to implement some form of electoral reform is politically divisive. Since reform stands to affect the number of seats each party wins in an election, the move to one system or another can arguably benefit one or more parties above others.

During the 2015 federal election campaign, the Liberal, NDP and Green Party each included electoral reform in its platform. Liberal leader Justin Trudeau was the most vocal, announcing that the party was “committed to ensuring that the 2015 election will be the last federal election using first past the post.” The Conservative Party supported a referendum on the matter.

After the Liberals won a majority, they established the all-party Special Committee on Electoral Reform on 7 June 2016. The committee’s report, tabled that December, recommended that the government consider a national referendum on the question of electoral reform. Although the report suggested that any new system adopted should be one of proportional representation, it did not recommend a specific alternative.

The government commissioned an online survey called MyDemocracy.ca, which was circulated in December 2016. Though its aim was to consult and engage Canadians on the subject of electoral reform, its results were inconclusive. Critics pointed out that the survey did not clearly discuss electoral reform or specific electoral systems and instead focused attention on democratic values.

On 1 February 2017, the Liberal government dropped electoral reform from its official mandate.

Legal experts point out that federal electoral reform may require constitutional amendment, a historically difficult process (see Constitutional History).

Electoral Reform in the Provinces

Electoral reform in the provinces is less complex than at the federal level, as the main requirement would be democratic approval in a referendum. However, in practice, it remains difficult. The decade from 2000 to 2010 saw a surge in interest for electoral reform at the provincial level in British Columbia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Québec. Despite the ambitious initiatives undertaken in each of these provinces, reform failed to occur in any of them (although New Brunswick and Ontario did adopt a system of fixed election dates during that time period).

British Columbia

In January 2004, the provincial government of British Columbia established the British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform, which, following nine months of discussion, proposed an STV system. In the provincial election held in May 2005, British Columbians voted on whether to adopt reform. The vote fell just short of the 60 per cent threshold required, with 57 per cent voting in favour of the proposal. In May 2009, a second referendum was held, in which the proposal garnered significantly less support: 39 per cent.

New Brunswick

Movement toward electoral reform began in New Brunswick with the establishment of the eight-person Commission on Legislative Democracy in December 2003. The commission released a report in January 2005 that endorsed the MMP option, and the government of Progressive Conservative Premier Bernard Lord responded by pledging to hold a referendum on the reform in May 2008. Lord’s government was defeated by the Liberal party in a September 2006 election, however, and the referendum was never held.

Ontario

The Ontario Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform was formed in 2006, and in May of the following year they released a report endorsing the MMP voting system. A referendum was held on the proposal in October 2007. It required 60 per cent support to pass, but failed, receiving only 37 per cent. Following the vote, Elections Ontario, the province’s non-partisan agency responsible for the administration of elections, was criticized by politicians representing all of the major parties for failing to adequately inform voters about the nature of the proposed reform.

Prince Edward Island

In 2005, a similar situation played out in PEI, where voters were faced with a referendum on MMP. The proposal received only 36 per cent support — a result that many proponents of the reform claimed was the result of an insufficient public education campaign by Elections PEI. A second referendum was held in 2016, in which a majority (52 per cent) voted in favour of MMP representation. However, Premier Wade MacLauchlan stated that government would not act on the result of the referendum — which was not legally binding — because voter turnout was too low (36 per cent) to reflect a clear majority decision. MacLauchlan proposed that another referendum be held in conjunction with the next provincial election.

Québec

In Québec, a Citizens’ Committee released a report in April 2006 that proposed an MMP voting system. The government did not respond with commitments to implement the proposal or hold a referendum on the matter.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom