Women’s suffrage (or franchise) is the right of women to vote in political elections; campaigns for this right generally included demand for the right to run for public office. The women’s suffrage movement was a decades-long struggle to address fundamental issues of equity and justice. Women in Canada, particularly Asian and Indigenous women, met strong resistance as they struggled for basic human rights, including suffrage.

Representative of more than justice in politics, suffrage represented hopes for improvements in education, healthcare and employment as well as an end to violence against women. For non-white women, gaining the vote also meant fighting against racial injustices.

(See also Women’s Suffrage Timeline.)

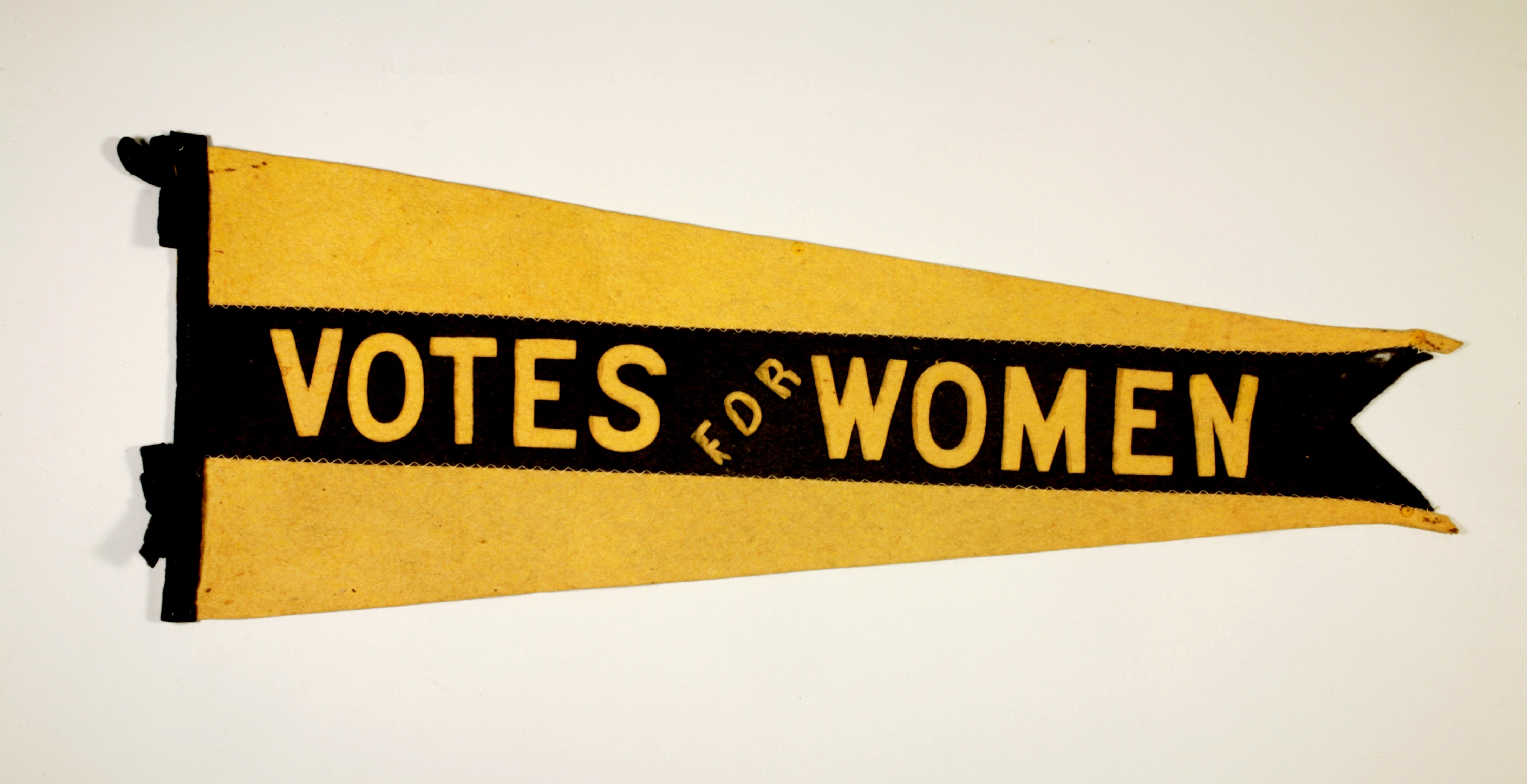

“Votes for Women” pennant (courtesy The Manitoba Museum, H9-38-198).

Early Voting Rights and Disenfranchisement

There were signs of some women being able to vote in the early 19th century in British North America, notably in Lower Canada but also in the Maritimes and Canada West. At least 27 Kanyen’kehà:ka women from Kahnawake, Lower Canada, cast ballots in an 1825 election. Some Catholic, Protestant and Jewish women with property also voted in early Quebec elections. After enslavement was abolished in 1834, Black women and men were not officially excluded as a group from the Canadian franchise.

Women’s right to vote was not to last, however. By the mid-19th century, full citizenship was legally limited to white men and most colonies removed women’s franchise. The British North America Act of 1867 specified that only “Male British Subject, aged Twenty-one Years or upwards, being a Householder, shall have a Vote.” By the end of the century, laws across Canada mandated near-universal, white male citizenship at the federal and provincial level and explicitly excluded female voters.

The necessity of being male to vote reflected the emerging Victorian idea of placing women and men in separate spheres. Women were idealized as guarantors of cultural survival, who had no place in political life. They were expected to remain at home, producing children and preserving culture. As French Canadians increasingly became a minority culture among English-speaking Protestants in British North America, women’s suffrage was seen as a particular threat to their national survival.

There was opposition to having independent women who were believed to be a danger to religious, ethnic or national communities. Exclusion from the franchise also remained acceptable to many Canadians because many women as well as men believed that men had greater capacity for reason and that men’s potential for military service justified more rights. Opposition would only dissipate as suffragists successfully redefined women as legitimate public subjects and the public sphere as a respectable space for women to exercise authority.

In 1885, House of Commons debates over a new federal franchise act (previously the right to vote was set by provinces) demonstrated the significance of suffrage in shaping the country. The decision to exclude all women, most Indigenous peoples (see also Indian Act) and all Asian persons was meant to preserve white men’s citizenship and the right to rule.

Rise of the Suffrage Movement

By the last decades of the 19th century, Canadian women increasingly protested against discrimination in education and paid employment as well as violence against women and children. One remedy was the suffrage campaign, which was led by many first-generation university graduates and female professionals in medicine, teaching and journalism. Suffragists advocated for the extension of suffrage to include women. They also insisted on the value of women’s maternal qualities in private and public life.

Early suffragists were typically white, middle-class women, many of whom believed that suffrage would increase the influence of their class and result in a better country. Many of these suffragists were not inclusive, however, and even advocated against non-white women getting the vote. Nonetheless, there were non-white advocates who fought for women’s suffrage such as Black abolitionists like Mary Ann Shadd. Shadd edited the Provincial Freeman and advocated for women’s rights. Suffrage was also supported by unionists, socialists and temperance activists.

The majority of Canadian suffragists relied on peaceful campaigning. Only a handful identified with the militant suffragettes led by Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928) and the Women’s Social and Political Union in the United Kingdom.

While they campaigned at every level of government for the vote, suffragists made their first inroads at the local level. Many Canadians believed that women’s mothering and domestic qualities were especially useful in managing local affairs. By 1900, suffragists had won municipal voting privileges for property-owning women in many cities, and some women could vote in elections for park, library and school boards.

Mary Ann Shadd, editor of the Provincial Freeman, was a pioneer suffragist and abolitionist, who used her newspaper as a platform to discuss women’s rights, including the right to vote. The paper also informed readers of suffrage meetings held in Canada and the United States. However, Shadd was marginalized as a Black woman and as an opponent of American slavery. Her influence was all the more minimal as she returned to the United States in the 1860s.

Emily Howard Stowe, from The Women's Suffrage Movement in Canada (courtesy Library and Archives Canada/C-9480).

In Ontario, widening public debate about suffrage and women’s rights produced the Toronto Women's Literary Club (TWLC). The TWLC was devoted to higher education and intellectual development as well as to the physical welfare and employment conditions of women workers. To the TWLC, extending the vote to women would help to improve women’s safety as well as their chances of employment and education. The TWLC was created in 1876–1877 by Emily Howard Stowe, one of Canada's first female doctors. She and her daughter, Augusta Stowe-Gullen, spearheaded Ontario's suffrage campaign for 40 years (see Women’s Suffrage in Ontario). In 1883, the TWLC became the Toronto Women's Suffrage Association, which in 1889 became the Dominion Women's Enfranchisement Association. From the 1880s on, many Ontario unionists and socialists, including Knights of Labor journalist Thomas Phillips Thompson, also endorsed women’s suffrage.

Suffragists were not a homogeneous group; nor did they focus only on suffrage. Campaigns also called for improved public health, equality in employment and education, social assistance and condemnation of violence.

Despite numerous petitions and private members’ bills, lawmakers across the country (with a few exceptions) repeatedly voted against the enfranchisement of women. Suffragists had to undertake long years of public education and agitation while facing repeated abuse. In the 1890s, critical support came from Canada’s largest women’s group, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The Union’s leaders believed the franchise would help introduce prohibition and thus reduce violence.

By 1914, women’s suffrage was seen as both a progressive and conservative cause. Growing urbanization, industrialization and immigration in the years before the First World War raised fears about how to integrate newcomers and control working-class Canadians. Some suffragists, especially those who were unionists and socialists, took up the cause of women workers, who were for the most part ill-paid and unprotected. Progressive members also championed suffrage early on as an expression of women’s right to equality while the respectable and cautious National Council of Women of Canada only endorsed the vote in 1910. Meanwhile, more conservative suffragists viewed the vote as a means of strengthening white middle-class power while oppressing non-white minorities and working-class Canadians.

The First World War interrupted the suffrage campaigns and divided activists. Many concentrated on supporting the war effort, including conscription, in groups such as Women’s Patriotic Fund. Socialist and pacifist suffragists preferred to place their hopes on an armistice and international collaboration. Some endorsed the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, formed in 1915. A Canadian, Julia Grace Wales, wrote the League’s founding document, “Continuous Mediation without Armistice.” During the war, Winnipeg suffragist and journalist Francis Marion Beynon left her job and moved to Brooklyn due in part to her opposition to the war. Beynon and Ontario pacifist and suffragist Alice Chown left moving testaments to their views in Aleta Dey (1919) and The Stairway (1921) respectively.

Suffrage in the West

Opposition to feminism seemed strongest in central and eastern Canada, while the western provinces appeared more receptive. The West’s greater openness to women’s suffrage can be interpreted as strategic: newly colonized regions relied on white settler women to guarantee the displacement of Indigenous peoples. The vote was to attract and reward white newcomers.

Though the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was a powerful advocate for the franchise in the West, the farm movement was at least equally influential. As early as the 1870s, the Manitoba Icelandic community was endorsing women’s suffrage.

Early Manitoba leaders included Margret Benedictsson, Amelia Yeomans, Francis Marion Beynon, E. Cora Hind and Nellie McClung. A popular author and member of the Canadian Women's Press Club, McClung became the Prairie movement's dominant figure. Her best-seller In Times Like These (1915) combined serious argument with satiric put-down of anti-suffragists. Manitoba’s Political Equality League, established in 1912, was a star-studded assembly of articulate and hard-working activists. In 1914, the League held a successful fundraiser with a well-publicized mock parliament, a tactic employed elsewhere as well.

On the stage of Winnipeg’s Walker Theatre, women played politicians, with Nellie McClung mocking Conservative Premier Sir Rodmond Roblin, as she debated whether or not to give men the vote. In 1915, suffragist support was critical to the victory of the pro-suffrage Liberal Party in the provincial election. (See also Women’s Suffrage in Manitoba.)

Victories in the West and in Ontario

Western suffragists found powerful supporters in the farm, labour and social gospel movements. Like men of their own class and community, Prairie suffragists never paid much attention to Indigenous women and were generally convinced of the superiority of Anglo-Celtic peoples. (See also Indigenous Women’s Issues.)

On 28 January 1916, Manitoba women became the first in Canada to win both the right to vote and to hold provincial office. Manitoba was followed by Saskatchewan on 14 March and Alberta on 19 April 1916. In these instances, the farm movement supported women’s suffrage as the proper course for a democracy. The WCTU’s determination to protect the home and to end violence against women and children strengthened the suffrage cause. British suffragette Barbara Wylie visited Saskatchewan in 1912. Her communications, like those by activists from the United States and the rest of Canada, affirmed powerful global ties among suffragists.

In 1914, a number of political equality leagues were created in Saskatchewan as well as the Women’s Grain Growers’ Association (WGGA). Farm journalist and president of the WGGA Violet McNaughton was Saskatchewan’s most powerful feminist for many years. In 1915, the WGGA and the WCTU collaborated to form the Provincial Equal Franchise Board. Their petition campaign ensured the Liberal government’s passage of a suffrage bill in 1916.

Alberta showed a similar groundswell of support. The United Farmers of Alberta endorsed suffrage in 1912, and three years later the United Farm Women of Alberta (UFWA) emerged to campaign for suffrage, temperance and improvements in health and education. By then, Nellie McClung had moved to the province and joined suffragists such as journalist Emily Murphy, WCTU leader Louise McKinney and UFWA activist Irene Parlby.

In British Columbia, campaigns drew most heavily on urban activists, notably in Victoria, where suffrage demands were pioneered, and Vancouver, which had assumed centre-stage by the First World War. Once again, the WCTU was influential, but so too were the local councils of women as well as university women’s clubs. British Columbia also produced various political equality leagues and welcomed suffrage speakers from the rest of Canada, the UK and the US. British Columbia’s socialist and labour movements were critical, with the BC Federation of Labour endorsing suffrage in 1912. As elsewhere in Canada, BC suffragists showed little interest in Indigenous or Asian women, who served more often as an inspiration for charity rather than for sisterly alliance. On 19 March 1913, the Vancouver Sun sold out a special women’s edition that, together with massive petitions, demonstrated the breadth of support mobilized against anti-suffrage Conservative governments in Victoria and Ottawa. Suffrage leaders such as Helena Gutteridge, Mary Ellen Smith and Laura Marshall Jamieson displayed the talents that would later make them successful elected politicians. British Columbia was the only jurisdiction in Canada to put women’s suffrage to a referendum of male voters, during the provincial election of 1916. Bolstered by the favorable results (43,619 to 18,604 ballots), the new Liberal government approved women’s suffrage on 5 April 1917. (See also Women's Suffrage in the West timeline.)

A week later, on 12 April 1917, Ontario suffragists caught up with the West. It was the first conservative government to pass women’s suffrage. Ontario produced the only suffrage organizations claiming a nation-wide mandate — the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association and Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association — but their campaigns were largely restricted to the province. Although the WCTU was the strongest provincial group in support of women’s suffrage, Ontario also produced charismatic non-conformists such as social reformer, writer and spiritualist Flora MacDonald Denison. Denison admired British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst and was a Canadian representative in giant protests in the UK and the US. (See also Women’s Suffrage in Ontario.)

Achieving the Vote in Federal Elections

During the First World War, pressure mounted on federal politicians in the Conservative — later the Union Government (1917) — of Sir Robert Borden. The government wished both to acknowledge women’s contribution to the war effort and to appeal to future female voters by extending the franchise; it also wanted to firm up support for conscription. The government also feared that voters, especially men, who were born in countries with which Canada was at war would oppose conscription. In the controversial Military Voters Act and Wartime Elections Act of 1917, the federal vote was extended to nursing sisters (women serving in the Canadian Army Medical Corps) and to close female relatives of military men. At the same time, the Wartime Elections Act disenfranchised thousands of immigrants from enemy countries who had become citizens after 1902 as well as all conscientious objectors (those who refused to go to war because it was against their religious, moral or ethical beliefs). The Act divided Canadian suffragists, many of whom opposed partial enfranchisement and disenfranchisement.

Once conscription was secured, the government began to argue that women had earned the right to vote through their war work. On 24 May 1918, female citizens, not included under racial or Indigenous exclusions, aged 21 and over became eligible to vote in federal elections regardless of whether they had yet attained the provincial franchise. In July 1919, enfranchised women gained the right to stand for the House of Commons, although appointment to the Senate remained out of reach until after the Persons Case of 1929. The Dominion Elections Act of 1920 continued to exclude voting rights on the basis of race in the provinces (this meant Japanese, Chinese and South Asians in BC and the Chinese in Saskatchewan). Similarly, Inuit and most First Nations were excluded from voting.

Atlantic Provinces

In Nova Scotia, women had been formally excluded from the provincial vote in 1851. In the 1890s, Nova Scotian women launched a campaign for the franchise. The suffrage movement was strongest in Halifax, where women championed progressive causes. Many activists were associated with the Local Council of Women and the WCTU. These included scholar and philanthropist Eliza Ritchie and Anna Leonowens, author of The English Governess at the Siamese Court (the inspiration for the play and film, The King and I). On 26 April 1918, women in Nova Scotia won the right to vote.

The WCTU was also critical from the 1880s onward in New Brunswick, where a bill to enfranchise single, property-owning women failed in 1870. Sixteen years later, that same small group won the municipal franchise. New Brunswick’s only group devoted to the vote was the Women’s Enfranchisement Association of New Brunswick, which was formed in 1894 in Saint John. Not until 17 April 1919 was New Brunswick’s 1843 prohibition of female voters finally revoked.

Prince Edward Island, which produced no popular agitation for women’s suffrage, revoked its 1836 formal exclusion of women on 3 May 1922.

The suffrage movement in Newfoundland, a Crown colony separate from Canada, was active from about the 1890s. In 1892, a suffrage bill supported by the local branch of the WCTU was defeated. Many Newfoundland suffragists were directly inspired by British campaigns, and in 1920, the WCTU and The Women’s Patriotic Association inspired the Women’s Franchise League, which fought hard to win women the vote. That right was eventually obtained on 3 April 1925. In Nova Scotia, PEI and Newfoundland, the right to stand for provincial office accompanied voting rights, but New Brunswick resisted that extension until 9 March 1934. (See also Women's Suffrage in Atlantic Canada timeline.)

Quebec

In Quebec, suffrage supporters came from both the French and the English-speaking communities, but the former was hobbled by the opposition of the Catholic Church and by nationalist fears. Montreal’s Local Council of Women included many strong suffragists, including McGill University’s Carrie Derick and Octavia Grace Ritchie England. Québécoise suffragists were led by McGill professor Idola Saint-Jean in the Canadian Alliance for Women’s Vote in Quebec and Thérèse Casgrain in the League for Women’s Rights. Their campaigns, in concert with some support from federal Liberal politicians, progressive provincial counterparts, as well as from the CCF (whose Agnes Macphail was a stalwart ally of Quebec suffragists), helped bring success on 25 April 1940.

Black Women

Enslaved Black men and women were unable to vote. After the abolition of enslavement in 1834, land-owning Black people were granted the right to vote. However, like other women, Black women were disenfranchised in subsequent decades across British North America on the basis of their gender. Unlike Asian and Indigenous women, Black women’s right to vote was not officially restricted on the basis of race and ethnicity.

Black women like Mary Ann Shadd advocated for women’s suffrage. Over time, Black women regained the right to vote as gender-based voting restrictions were repealed at the federal and provincial levels. (See Black Voting Rights.)

Asian Women

Asian residents were explicitly excluded from the vote under the 1885 federal franchise legislation. The 1920 Dominion Elections Act did not exclude Canadians of Asian heritage explicitly, but the Act stated that persons disenfranchised “for reasons of race” by provinces would not get the federal franchise. Since Chinese, Japanese and South Asians were excluded from the vote in British Columbia, as were the Chinese in Saskatchewan, members of those communities could not vote at the federal level in those provinces. Despite continuing protests, Asian women and men waited until 1948 to receive the vote, the year of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which Canada helped to draft and then adopted.

Indigenous Women

Indigenous women were largely invisible in the suffrage campaigns. The vast majority of Canadian suffragists were of European origin. While some were sympathetic to Indigenous women, none campaigned to include First Nations or Inuit in legislation and most accepted the commonplace assumption that Status Indians were a “dying race.” Kanyen'kehà:ka-English writer and performer, Pauline Johnson, challenged that designation.

Indigenous women worked locally to improve conditions for their communities. As non-voters, they lobbied band councils, much as suffragists elsewhere pressured other levels of government. The 1934 Dominion Franchise Act explicitly denied the franchise to Status Indians on reserves and to Inuit in the north. Until 1951, the Indian Act also barred many Indigenous women from voting for or holding office in their bands. Inuit received the vote in 1950; however, their names were rarely added to official lists of people entitled to vote, and ballot boxes were not brought to Inuit communities in the Arctic until 1962. Ottawa finally extended the right to vote to all Indigenous people, women and men, in 1960. Both sexes continued, however, to question the value of a right to vote in a nation dominated by settler communities that resisted equality. (See also Indigenous Women and the Franchise; Indigenous Women’s Issues; Indigenous Suffrage.)

Women in Politics

Once women won the vote, they encountered considerable resistance in entering politics. In 1921, Agnes Macphail became the first woman to win a seat in the House of Commons, representing the United Farmers of Ontario. The second, Martha Black, replaced her ailing husband in 1935 as Conservative MP for Yukon. The third, Saskatchewan’s Dorise Nielsen (associated with the CCF and then the Communist Party of Canada), arrived in Ottawa in 1940 but found little support. The first Indigenous female Member of Parliament was the Liberal Ethel Blondin Andrews for Western Arctic, Northwest Territories, in 1988.

In 1917, Alberta’s Louise McKinney of the Nonpartisan League was the first woman elected to a provincial legislature in Canada and the British Empire (followed closely by Roberta MacAdams, elected by soldiers and military nurses). Numbers grew slowly. In 1941, British Columbia had five female MLAs, the largest number in any legislature until the 1970s. In 1957, Conservative MP Ellen Fairclough became the first woman appointed to a federal Cabinet. In 1996, British Columbia elected the first Chinese Canadian women to its legislature: Liberal Ida Chong and NDPer Jenny Kwan.

Real advances in numbers, which depended on the resurgence of feminism, awaited the end of the 20th century. Feminist Kim Campbell became prime minister of a short-lived Conservative government in 1993. The 2019 general the House of Commons — 29 per cent of MPs elected. To much approval, the Liberal government announced an unprecedented Cabinet with 50 per cent female ministers.

The first female senator, Liberal Cairine Wilson, was appointed in 1930 and by 2016 there were 33 women senators. The first female premier of a province or territory was Rita Johnson (Social Credit) of British Columbia in 1991.

Significance and Legacy

The other test of suffrage rests with legislative outcomes. While modern polling often suggests that female voters disproportionately favour more liberal causes, little attention has been paid to post-suffrage results. It is clear, however, that the suffrage movement everywhere endorsed improvements in education, healthcare and social services that would better lives for women and children. The introduction of provincial mothers’ allowances or pensions beginning in the First World War would not have occurred without feminist pressure and politicians’ fears of new voters. It is also no coincidence that Canada’s general, if imperfect, experiments with social security in the 20th century coincided with some 50 per cent increase in the electorate. As democracy became nearly universal, governments were forced as never before to begin to address issues of equity and justice. Women’s suffrage was essential to that advance.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom