The fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) is the second-largest animal on Earth. It is built to move through water at fascinating speeds, rarely breaches the surface for humans to witness and is known for the unique colouring on its lower jaw. In Canada, this baleen creature, also known as the finback whale, was brought to near extinction through 20th-century whaling practices. However, they have made a slow comeback since commercial whaling ended in the 1970s. Nowadays, fin whales are found on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts in Canada, as well as all over the world.

Physical Description

Fin whales have dark brown-grey pigmentation on their backs and white on their underside, but are most identifiable by their unusual asymmetrical colouring on their lower jaw, which is always dark on the left and light on the right. Second in size only to the blue whale, their long and narrow body, growing up to 25 m, allows them to move through the water at top speeds — earning them the nickname “greyhound of the sea.” A distinctive fin near their tail, about two-thirds of the way down their back, gives them their name.

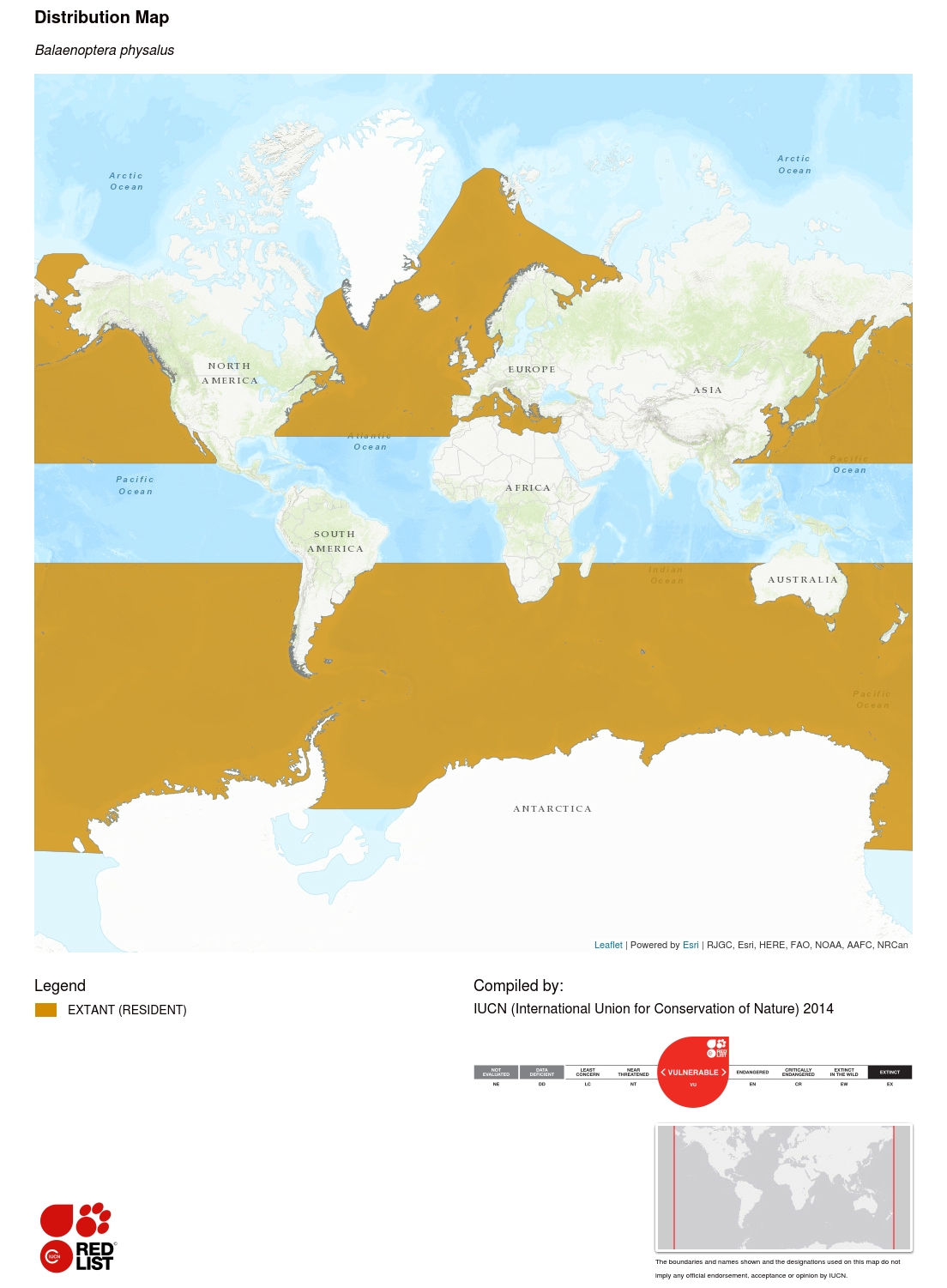

Geographic Distribution and Habitat

Fin whales are found all over the world, except for parts of the Arctic that are covered in ice. In Canada, these creatures can be found year-round, though they typically migrate to higher latitudes in summer for feeding and lower latitudes in the winter for breeding. In the Atlantic, they are found in a variety of habitats, from the deep canyons in the Gulf of St Lawrence to the shallow areas in the Bay of Fundy. In the Pacific, these whales are found along the continental shelf in both open and coastal waters. Recently, they have been spotted in narrow fjords and channels along the British Columbia coast, where they were driven out of due to commercial whaling in the 20th century.

Many experts consider fin whales found in Atlantic, Pacific and southern hemisphere waters different subspecies since they almost never intermix.

Lifespan and Reproduction

The fin whale has a lifespan of up to around 100 years, but they reach physical maturity at age 25. Once they reach sexual maturity — which occurs between 6 and 12 years old — a female will give birth to one calf every two to three years. With a gestational period of 11–12 months, a newborn calf will be about 6 m long and weigh between 1,800 and 2,700 kg In Canada, most births occur between October and February.

Diet and Behaviour

Following the pattern of other baleen creatures, the fin whale’s diet consists of krill, copepods and small schooling fish like herring, capelin and sand lance. Often lunging into schools of prey with their mouths open, they expand their around 50–100 throat pleats to capture large amounts of food and water, then utilize their around 260–480 baleen plates to filter out the water. Their food consumption significantly increases in the summer, eating up to two tonnes of food daily, then decreases to a fast in the winter.

Relationship with Humans

During the 20th century, fin whales were nearly depleted due to commercial whaling. Since those practices largely ended in 1972, the population has slowly recovered on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Indigenous Peoples are authorized to hunt whales under certain conditions, and the Canadian government establishes the total allowable harvests. If a whale were to be hunted, the majority of the animal must be used within the local community.

Today, spotting a fin whale on a whale-watching expedition is most likely to occur on the Atlantic Coast, largely in the Bay of Fundy.

Status and Threats

The fin whale is listed as Threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA) in the Pacific and of Special Concern in the Atlantic. While they have partially recovered in population size in the 1970s, these baleen creatures still face many anthropogenic threats that put them in danger.

As one of the most susceptible species to ship strikes, fin whales are at high risk of colliding with vessels on both coasts. With a progressive increase in ship traffic throughout the years, more vessels are entering fin whale territory, making them more likely to barrel into each other. This often results in fatality, though there have been many sightings of fin whales with deep wounds and propeller scars on their bodies. It is difficult to determine how many fin whales have been injured or killed by ship strikes due to a lack of investigation and under-reporting.

Disruptive noise caused by these vessels, as well as by seismic mineral exploration or military exercises, can be extremely harmful to many ocean dwellers, including fin whales. Consistent exposure to this noise has been shown to disrupt baleen whale behaviour, presenting as stress, temporary or permanent hearing loss, acoustic and communication changes and displacement of habitat. In some cases, intense noise pollution has resulted in fin whale fatality.

Entanglement in fishing gear is a consistent threat to baleen creatures, as it most often wraps around their mouth, fins and tail. This results in fatigue, injury, reduced feeding abilities and, sometimes, death. While it is difficult to determine how many fin whales are affected by entanglement due to under-reporting and difficulty in observing fin whales, as they rarely reveal their entire body when breaching, multiple fin whales have been found with fishing gear wrapped around them.

Conservation

While fin whale abundance has grown since the 1970s, conservation efforts continue, especially as new threats like ship strikes and noise pollution present themselves. Fisheries and Oceans Canada oversees the conservation of fin whales in the country and outlines best management practices to protect the animal. This includes more thorough research to determine population, distribution and habitat characteristics, as well as dedicated outreach to educate stakeholders and the general public on fin whales. Parks Canada also plays a role for whales present within National Parks.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom