As tourists stroll through the legislative buildings in Victoria or refresh themselves with tea at the Empress Hotel just down the street, they would not be surprised that the man who designed these historic buildings was the leading architect of his day in British Columbia. What probably would surprise them however, is that seventy years ago this same man was also at the centre of one of the most sensational high-society murders in the British Empire.

During the height of his success, Francis Mawson Rattenbury seemed an unlikely object of scandal. He had arrived in British Columbia from his native England in 1892, a 25-year-old architect of meagre experience but full of charm and self-confidence. Within ten months of his arrival he had entered, and won, a competition to design the new Parliament Building planned for Victoria. The commission was a great coup, and Rattenbury went on to establish a flourishing practice, designing such notable buildings as the Vancouver Court House (now the Vancouver Art Gallery), the Crystal Garden in Victoria, and assorted banks, homes and hotels all over the province. At one time he was the chief architect for both the CPR and the Bank of Montreal, twin pillars of the economic establishment.

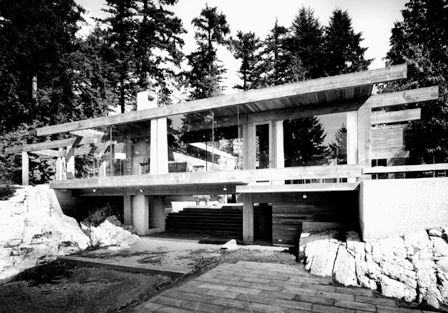

Rattenbury's professional success propelled him into the front ranks of Victoria society. Soon after the Parliament Building opened he married Florence Nunn, the daughter of a retired British Indian Army officer. The couple lived with their two children in a beachfront home in Oak Bay while Rattenbury turned out a succession of high-profile commissions and even served a term as reeve of the municipality.

Behind this façade of public success, however, the architect's personal life deteriorated. He and Florence were ill-suited and grew to dislike one another. They remained together, but Rattenbury lived in his own part of the house and only communicated with his wife through their daughter. Drinking excessively, he grew gloomy and reclusive.

Enter the femme fatale. At a dinner in his honour at the Empress Hotel at the end of 1923, Rattenbury met Alma Pakenham and was smitten. Alma was beautiful, talented and exotic. Still in her twenties, she already had lost one husband in the war and divorced a second. She herself had served as a transport driver and nurse at the front, where she was twice wounded. An accomplished musician, Alma was visiting Victoria from her home in Vancouver to give a recital, but within weeks of their meeting she had set up shop in the capital as a music teacher.

Alma and Rattenbury carried on their affair openly, with no concern for public opinion or Florence's feelings. They appeared together at social functions and gossips circulated the rumour that the pair were sharing a cocaine habit as well as a bed. When Florence refused to grant him a divorce, Rattenbury began entertaining his mistress at the family home in Oak Bay. "The man's bewitched," was the opinion of Rattenbury's longtime friend, the architect Sam Maclure.

Florence finally gave in and granted Rattenbury his divorce. In the spring of 1925, he and Alma married. But their affair had left them social pariahs, even after they had a son and settled into a respectable domesticity. At the end of 1929 they packed up and moved to England, settling in the coastal resort town of Bournemouth.

England was not a cure for Rattenbury's discontent. As the years passed, he became a sulky, impotent, alcoholic old man, burdened with financial worries. Alma, on the other hand, was still young and enjoying success as the composer of popular songs. Inevitably, she took a lover, and her choice showed her usual carelessness. George Stoner was an 18-year-old school dropout, hired to be Rattenbury's chauffeur. Besotted with Alma, jealous of her husband, afraid that the two might reconcile and toss him out, he was a ticking bomb waiting to go off.

The explosion occurred on the evening of March 24, 1935, when George took a mallet and beat Rattenbury's head in while the architect sat in a drunken stupor. Both Alma and George were charged with murder. Their trial gave the British public everything it could have wanted: sex, drugs, celebrity and, in the end, tragedy. After five days of titillating testimony, a jury took 50 minutes to find Alma innocent and her young lover guilty.

The story that began with a fateful meeting in the Empress Hotel on a winter evening in 1923 ended four days after the verdict when Alma committed suicide by stabbing herself through the heart and falling into the River Avon. Apparently she expected that Stoner would hang, as did the judge who sentenced him to death. But an outraged public blamed Alma for corrupting the boy and when presented with a clemency petition signed by 350 000 people, the Home Secretary agreed. Stoner got a life sentence instead, and was out of prison in seven years, the sole survivor of British Columbia's most notorious love triangle.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom