The Colonists

In 1754, the population of New France was 55,000. The colonists had come from various regions in France over more than a century, and mainly lived in the cities and seigneuries of the St. Lawrence River Valley.

At the end of the Seven Years’ War, France, Great Britain and Spain ratified the Treaty of Paris (1763). France ceded the majority of its North American possessions, including Île-Royale (Cape Breton Island), Canada and the Great Lakes Basin. It also gave up the territories east of the Mississippi — which at that time were eastern Louisiana — except for New Orleans, having given western Louisiana to Spain in 1762. It retained fishing rights in part of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and repossessed the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon.

Paris was not encouraging emigration to its former colony. London was wary of this, since it already needed to pacify the French habitants for fear of them joining the Americans, who were in the midst of a full-fledged revolution (1775–1783). These upheavals, combined with the outbreak of the French Revolution (1789–1799) caused French emigration to decelerate significantly. In fact, from 1760 to 1850, only about 1,000 French people immigrated to Canada. Yet, during the same period, the blazing growth of the United States attracted a quarter of a million.

The rare French people who chose to immigrate to Canada were craftspeople, clerks, teachers, artists and members of liberal professions. They came in hopes of gaining some social mobility or sheltering themselves from religious persecution by a republican and secular France. For the most part, they settled in Montreal and Quebec City. Among them was Pierre Guerout, a Huguenot who in 1792 was elected to the first Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada. In Upper Canada, Count Joseph-Geneviève de Puisaye, convinced around forty French people to settle north of York.

For decades already, the banks of the Gulf of St. Lawrence had been attracting fishers and entrepreneurs from Brittany, Jersey and Guernsey — the latter making up the entire population of Grande-Grave and half that of Saint-Georges de La Malbaie, in Gaspésie. Often bilingual, these migrants would speak in the language of their Acadian, American or British clientele.

From Canso and Arichat, Nova Scotia, to Gaspé and Paspébiac (Quebec), the Robin and Le Boutillier families employed thousands of Acadian and French-Canadian workers. Using a credit-based sales system, these families provided fishers with fishing gear and food supplies in exchange for payment in codfish at the end of the season. The families were also influential in politics and held the positions of advisor, parliamentary representative and Justice of the Peace. French immigration slackened in 1904 when France gave up its rights to fish on Canadian coasts; these rights had been guaranteed in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), but which Newfoundland had been disputing since the mid-19th century (see also History of Commercial Fisheries).

Religious Settlers

French immigrants’ influence in the British colony was heavier than their demographic weight. This was because many such immigrants were professionals or religious practitioners who contributed to rebuilding and shaping a French-Canadian elite in the 19th and 20th centuries.

For one thing, 51 refractory priests immigrated to Canada during the French Revolution and breathed new life into the Canadian Catholic Church. They founded new parishes from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Upper Canada via Saguenay and the Eastern Townships, introducing their traditions and renewing devotion to ancien régime France.

In Nova Scotia, Jean-Mandé Sigogne re-established religious practice in Saint Mary’s Bay starting in 1799. He also established schools there and acted as an important intermediary between this isolated, illiterate population and the British authorities.

In 1806, Jean Raimbault was appointed superior of the Nicolet Seminary (founded in 1803); he served in that capacity until his death in 1841. The French religious immigrants were generally well liked by the bishops and their congregations, but they also aroused jealousy in their Canadian colleagues. The French were better trained and were sometimes the favourites to hold priest and administrative positions. They looked down on the Canadians sometimes and monopolized power in the congregations of the time.

After the Rebellions of 1837–38, the French-language clergy’s collaboration with the British authorities gave rise to new Catholic congregations, beginning in 1841. The bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget, succeeded in attracting Jesuits from Paris and the Oblates of Marie-Immaculée from Marseille. While a gust of secularism was blowing through France, at least 2,000 Catholics seeking a more hospitable environment and not fewer than 29 congregations — female and male — put down roots in Canada.

The arrival of these religious settlers enabled the French-Canadian Church to increase the number of French-Catholic schools, colleges, hospitals, orphanages, co-operatives and associations. The Church’s sizeable structure also made it possible to increase the number of Canadian recruits. In 1850, Canada had 650 francophone nuns — by 1920, they would total 13,579. The number of priests and brothers would rise from 788 to 6,536.

In Quebec and other French-Canadian migration destinations in North America, it was the Church that founded modern institutions. Between the mid-19th and mid-20th centuries, religious colonists built and ran most of the colleges and hospitals serving French Canadians. They accounted for two-thirds of male teachers and a quarter of female teachers in French and bilingual schools.

Religious settlers had a significant influence on religious practice in French Canada, as well as on the traditionalism of its secular elite. In part because of the elite’s ascendancy over the French Canadians, the latter had large families and saw defending their homeland as inseparable from defending their faith. Religious settlers also contributed to renewing ties with France, developing French-Canadian literature and advancing literacy, which leapt from 26 per cent to 87 per cent between 1840 and 1910.

Farmers

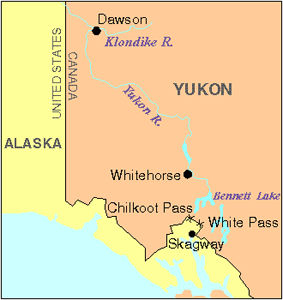

A rapprochement between France and Canada came about in the mid-19th century. This was thanks to the visit from a corvette called La Capricieuse (1855), the first French warship to sail in St. Lawrence waters since the Conquest, and also due to the establishment of a French consulate in Quebec City (1859). In addition, the gold rush on the Pacific coast and the prospect of another Canadian conquest were making mouths water in Europe.

In Canada, fears of the United States annexing the West spurred authorities to occupy the land more quickly. Furthermore, farmland in Quebec was dwindling, pushing French Canadians to clear Quebec backcountry as well as land across the border in New Brunswick, New England, Ontario and the Canadian Prairies.

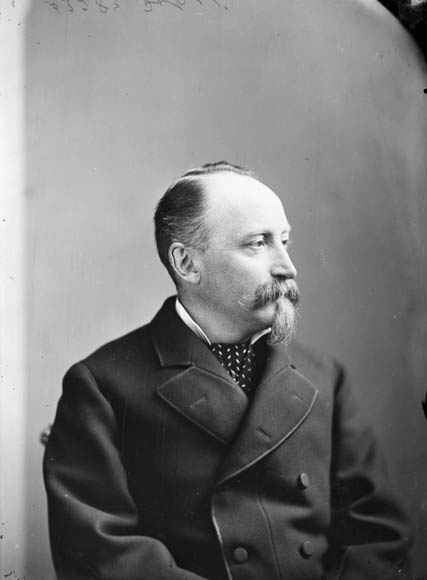

The French Canadians were unable to bring the land under cultivation fast enough. In response, the governments and the Church used several methods to attract French immigrants — Canadian agents posted in France, transatlantic exchanges within Catholic congregations, and the promotional Paris-Canada magazine. This magazine was created by Hector Fabre, the first agent general of Quebec and of Canada in Paris. The number of French immigrants went up, and the need for support was significant enough to justify training half a dozen sections of the French Benevolent Society.

Though the French tended to mix with French Canadians in Montreal, they sometimes founded independent communities in the Prairies, while still associating with French Canadians, Métis and other European immigrants. They maintained relationships with those groups that were sometimes accommodating, sometimes conflictual. Moreover, the Canadian government was seeking above all to encourage British immigration (a preference that rather easily stretched to include other immigrants from Western Europe) and intra-Canadian migrations. However, French Canadians were hesitant to relocate to areas where Anglo-Protestant authorities were openly hostile towards the teaching of Catholicism and the French language. Ottawa favoured recruiting Europeans because of their agricultural experience, and compared to French Canadians, the French were less skeptical about learning English or confining their Catholic traditions and French language to their homes. Accordingly, many of them travelled to French ports to board vessels subsidized by the federal government.

In an effort to extend its foreign relations beyond the British Empire, Canada founded a Department of Foreign Affairs in 1909. Soon, one of its first “legations” opened in Paris in 1928 (see Diplomatic and Consular Representations). Nearly 20,000 French immigrants went through the government and ecclesiastical recruitment channels, but these families and individuals were from various regions and were not necessarily connected to one another. Most of those immigrants, driven out by the saturation of the French countryside, dreamed of improving their socioeconomic standing. In 1911, 42 per cent of them were farmers, 16 per cent were skilled tradespeople and 11 per cent were non-qualified workers. By 1935, the percentage of farmers had climbed to 70 per cent.

However, nothing about their new life was easy. The settlers had to deal with the harsh winters, know how to tend livestock, learn English, and manage the perpetual risk that comes with farming in the Prairies. In 1941, half of the French migrants were located in Western Canada and 35 per cent resided in Quebec. Some immigrants integrated well and discovered the advantages that the new country had to offer them, particularly the abundant harvests and greater ease of finding a suitable partner to marry. Others struggled to tame the environment and suffered from homesickness, but integrated as best they could.

French migrants were proportionately few among the immigrants, and they came from regions as diverse as Touraine, Auvergne, Savoy and Le Midi. Consequently, they associated themselves either with other francophones — who totalled just 6 per cent of the population in the Prairies in 1921 — or with the anglophone majority, aware as they were of the socioeconomic advantages of doing so. This mixing made its mark on parishes in the Prairies more than those in Quebec and Acadia. The face of Frenchness was thus changed by new arrivals from France, Switzerland and Belgium. However, the increasingly close-knit francophone network, combined with the xenophobia that became apparent at the start of the century, contributed to marginalizing the Métis.

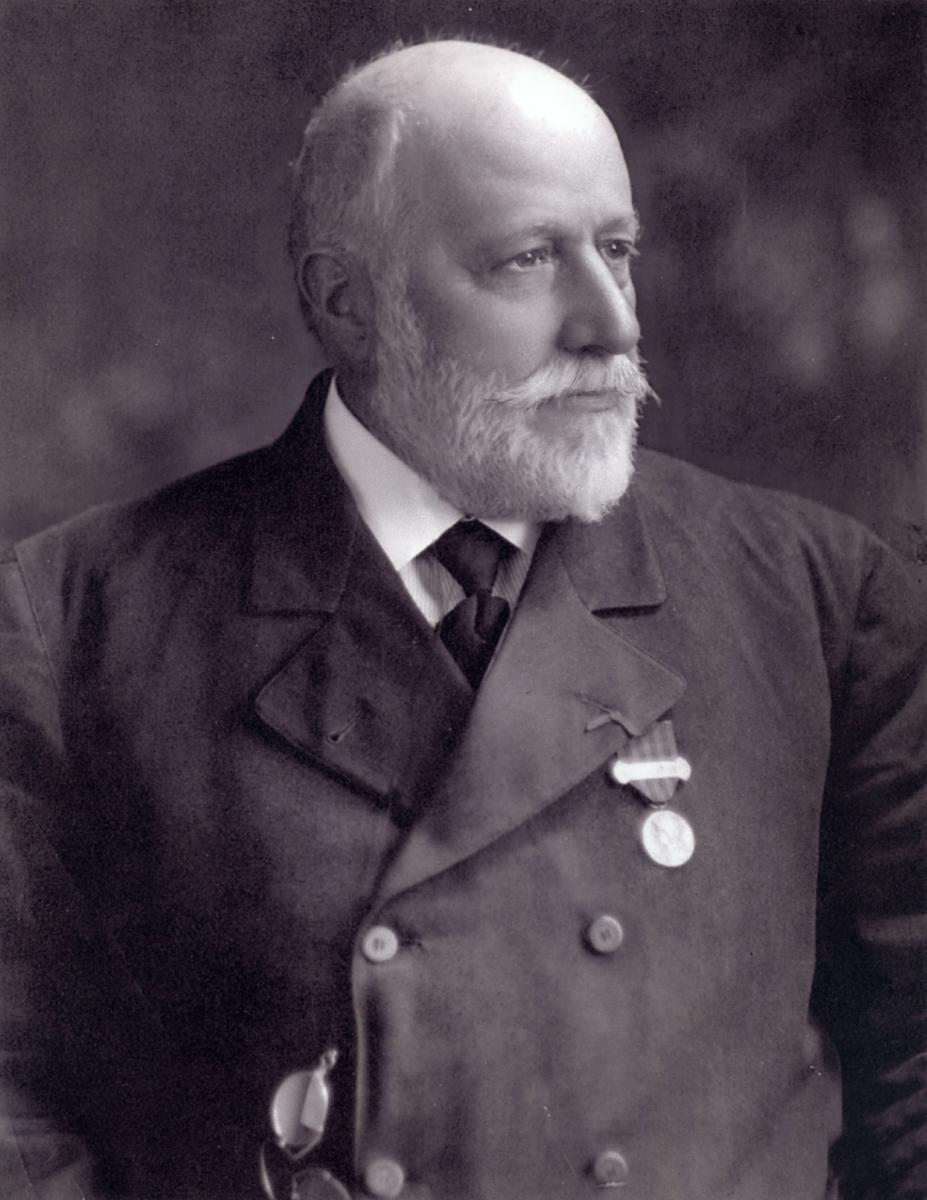

The French also played a fundamental role, alongside the Belgians, in creating the first French-language newspapers (such as the Patriote de l’Ouest), theatres (the Cercle Molière) and radio stations. In Quebec, the Alsatian Jew Jules Helbronner became head writer at La Presse and chaired the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital in Canada. In Saskatchewan, the Charentais Raymond Denis worked in the Franco-Canadian Catholic Association of Saskatchewan (1912) to recruit francophone teachers and oppose the restrictions on teaching in French that had been announced.

Despite Raymond Denis’s loyalty to the French-Canadian cause, some clerks were suspicious of him because the French appeared more independent from the Church institution. Meanwhile in Alberta, when the First World War began, the loyalty that some military immigrants had for their country of origin saw them return there for good.

Professionals and Entrepreneurs

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, French Canadians were not necessarily in favour of immigration because it created competition for the rare jobs available. The French community’s cohesion in Canada during this period is difficult to get a handle on. For instance, no Canadian city had a “French Quarter,” and although Alliances Françaises had existed since the late 19th century, it proved more difficult to unite French immigrants than immigrants from other communities of European descent. Thus, Gabriel Bonneau, Charles de Gaulle’s representative in Canada, was not able to rally his compatriots behind the general until 1943.

After the Second World War, the Canadian government wanted to encourage immigration, and in 1948 began to consider the French to be as desirable a cohort as the Americans and the British. The Canadian Embassy in Paris received up to 5,000 requests for information per month, but France halted the exodus because it needed labourers to rebuild the country. Between 1945 and 1960, Canada received 46,543 immigrants from France — a modest influx in comparison to those from the United Kingdom (594,092), Italy (259,821), Germany (234,679) and even the United States (151,519). Nevertheless, in 1972, the number of French expatriates in Canada reached 106,700.

When the Élysée began to concern itself with Quebec’s political future, cultural and economic collaborations with the province proliferated. Specifically, “France-Canada” associations, student and professional exchange programs, and the Cultural and Technical Co-operation Agency were founded (see Francophonie and Canada). With that said, on the commercial front, trade within the continent continued to dominate. The need for francophone professionals in Quebec and Ontario meant that French immigration was concentrated in those two provinces (respectively 66 per cent and 18 per cent) in 1981.

Quebec and the Prairies had been in the habit of welcoming the French for decades. By contrast, French Ontario did not take an interest in them until the 1950s, when the French-Canadian elite sought to preserve the Franco-Catholic character of the rural areas in eastern and northeastern Ontario. Common identity traits meant that the French — after Quebecers and Acadians — were Franco-Ontarians’ closest relatives. Therefore, the elite began to advocate for receiving the French into their community, too many members of which were integrating into the Anglo-Protestant majority of the day. “It is important to seek out their friendship,” Franco-Ottawan speaker Antoine Titley said in November 1950, suggesting that “social clubs” become the preferred venues for nurturing these friendships. However, anticlericalism and a condescending regard from some French people seemed to slow this process.

In 1962, the federal government eliminated national origin as a selection criterion for immigration candidates (see Immigration Policy in Canada). Then in 1967, it allowed permanent residents to sponsor candidates and favoured candidates who knew either of Canada’s official languages (see Official Languages Act of 1969). Though this “opening” increased the proportion of non-Western immigrants, the number of French did also climb slightly. Thanks to the immigration policies but also the need for professional francophones in the market and in communities, Montreal was home to 56,805 French in 2016 and Toronto to 6,895 (or 10 per cent of francophones in that city). A total of 86 per cent of francophone immigrants took up residence in urban settings (the cities of Montreal and Quebec alone received 62 per cent).

In 1978, the federal government gave Quebec the responsibility of choosing its own economic immigrants (the Couture-Cullen Agreement). Of the immigrants who settled in Quebec, 63 per cent now had French as their first official language spoken (FOLS). In the other provinces of Canada, only 2 per cent did.

Today, urban francophone communities — from Vancouver to Halifax — are profoundly marked by the ethnic diversity of their members (African, Caribbean, Arabic, Asian, European and South American). Here, the French have become a minority even among francophone immigrants.

This shift is reflected in the fact that documentation and research on immigrants from France specifically was plentiful up until the 1980s. Nowadays, however, nearly all this material is written about French FOLS immigrants as a whole.

The ever more cosmopolitan face of these communities makes social integration, belonging and cohesion more complex. At times, migrants confine themselves to their ethnic ties and maintain few relationships with other francophone immigrants and fewer still with Acadians, Franco-Ontarians and Quebecers. At the other end of the spectrum, rural and regional communities — which generally have too small a population and have the capacity to welcome more people — receive fewer new arrivals, owing to a lack of jobs or visibility. Public policies sometimes lag behind the needs on the ground.

Recent Immigrants and Maintenance of the French Language

At present, a large proportion of francophone immigrants in Toronto and Vancouver send their children to English school. As it turns out, English attracts even francophones. Still, French-language school attendance is the best way to foster integration into the French-Canadian community. English, bilingual and pluralist schools are facing a dilemma, which sociologist Monica Heller summarizes as follows:

Benefitting from the contribution of new groups (e.g. immigrants, Quebecers, anglophones, bilinguals, etc.) while not losing sight of the main objective: maintaining and promoting the French language and culture.

In contemporary pedagogy, the student is viewed as an intermediary between their parents and the history, culture and political demands of the host francophone community. The establishment of a “renewed culture” among youth remains a work in progress. In fact, parents do not have the time to get involved in the community, and immigrants identify very little with it. As a result, a slight majority of Toronto and Vancouver youth with francophone immigrant roots assimilate into the anglophone majority. By contrast, those who live in smaller communities or in cities that are more francophone assimilate much less.

The incoming stream of francophone immigrants is essential for the maintenance of French in Canada, and communities have very much reoriented their nationalist discourse to promote integration of diversity in a local and global Francophonie. However, that stream has still not managed to put the brakes on the slow decline in francophones’ proportional weight in Canada (which dropped from 26 per cent in 1961 to 21 per cent in 2016).

During the decade from 2005 to 2014, 85 per cent of francophone immigrants settled in Quebec, clustering in the environment best suited to receive them. This disadvantaged francophone communities in minority settings, which need more such immigrants to counter the effects of assimilation.

Today, most francophone immigrants still come from France, closely followed (and sometimes slightly overtaken) by those from Haiti. The Democratic Republic of Congo, Lebanon, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Guinea are also emerging sources for francophone immigration in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom