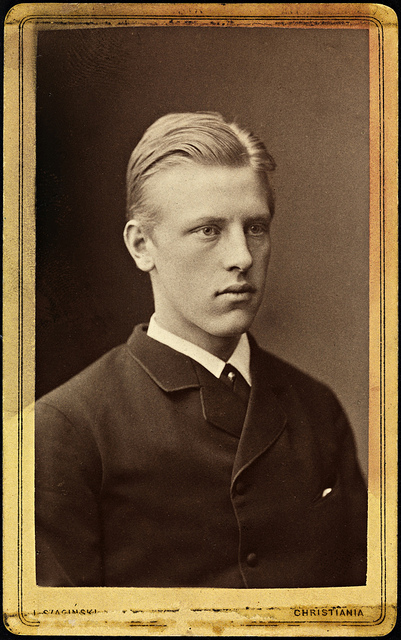

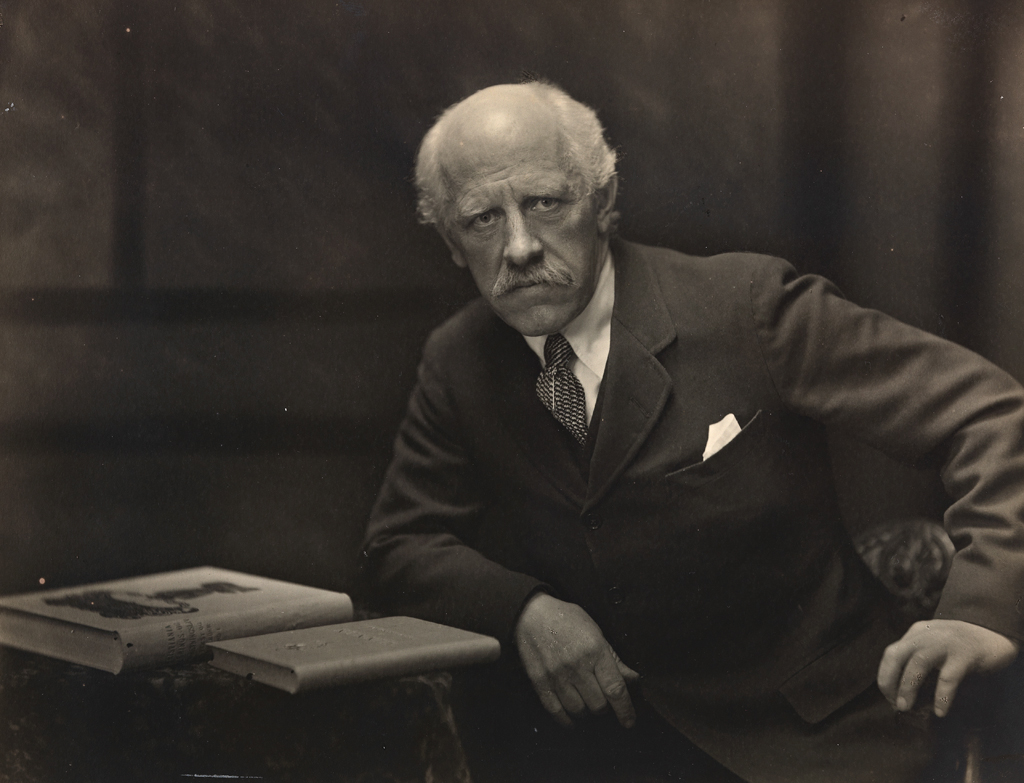

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen, arctic explorer, scientist, artist, author, diplomat, humanitarian (born 10 October 1861 in Christiana [later Kristiana, now Oslo], Norway; died 13 May 1930 at Polhogda, near Oslo, Norway). Nansen was an influential polar explorer, one of several Norwegian adventurers (such as Otto Sverdrup) who explored the arctic. The Nansen sled, which he based on a traditional Inuit design, was used by renowned polar explorer and Geological Survey of Canada glaciologist Roy Koerner and is still in use today. Among his many accomplishments, Nansen won the 1922 Nobel Peace Prize “for his leading role in the repatriation of prisoners of war, in international relief work and as the League of Nations' High Commissioner for refugees.” In 1986, Canada became the first nation to receive the Nansen Refugee Award.

Early Life

Fridtjof Nansen was the elder of the two surviving sons of Baldur Fridtjof Nansen, a lawyer, and Adelaide Wedel-Jarlsberg, the niece of one of the authors of the Norwegian Constitution of 1814. Both Baldur and Adelaide had been married previously, and Nansen had six older half-siblings. Nansen grew up near the Nordmarka forest and enjoyed hunting, fishing and skiing.

Education

In 1881, Fridtjof Nansen began studying zoology at Royal Frederick University in Kristiana (the spelling of the city name changed in 1877). From 1882 until 1886, he served as junior curator of zoology at the museum in Bergen. He became interested in arctic exploration after his scientific work on the Viking seal-hunting ship, which traveled to northern Greenland in 1882. In 1884, Nansen traveled across Norway from Bergen to Kristiana and back on skis. During his time in Bergen, Nansen also took courses in drawing and watercolour painting, learning lithography to create the illustrations in his doctoral dissertation.

Greenland

In 1888, Fridtjof Nansen defended his doctoral dissertation at the University of Kristiana (the first Norwegian doctoral dissertation in neuroscience). Four days later, he departed for Greenland to lead an expedition to traverse the interior. Nansen and his five-man team, which included Otto Sverdrup, became the first Europeans to travel across Greenland overland from east to west, traveling from Umivik to Godthåb (now Nuuk) on skis over a six-week period. During his winter in Godthåb, Nansen studied Inuit culture and technology and wrote an 1891 book about Inuit life, describing them as “highly gifted people, who lived well” and expressing concern about the impact of contact with Europeans on their way of life. The successful crossing of Greenland made Nansen a celebrity, and his 1889 book The First Crossing of Greenland became a bestseller. In 1891, he was awarded the Patron’s Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.

Fram Expedition

From 1893 to 1896, Fridtjof Nansen led an arctic expedition aboard a specially designed ship, the Fram (Norwegian for “forward”). He intended to reach the North Pole by allowing the ship to become trapped in Arctic Ocean ice and then move with the ice along ocean currents over the pole from Siberia to Greenland. In March 1895, Nansen and one of his crew, Hjalmar Johansen, left the Fram in the ice under the command of Otto Sverdrup and traveled north by dog sled. They came within 400 kilometres of the North Pole before ice conditions forced them to turn back. Nansen and Johansen were found on Northbrook Island by British arctic explorer Frederick George Jackson and returned to Norway, where they were reunited with Sverdrup and the rest of the Fram’s crew. Throughout the expedition, Nansen had employed Inuit techniques for traveling in the Arctic, including the use of sled dogs.

Although Nansen did not reach the North Pole, the expedition gathered valuable scientific data, including samples of marine life, meteorological observations, analysis of the northern lights (aurora borealis), the study of ice formation and under ice currents and tests of the depth and salinity of the Arctic Ocean. Nansen established that there was no landmass in the Arctic, as there is in Antarctica. After his return from the Arctic, he became a research professor at the University of Kristiana, publishing six volumes of scientific observations from the Fram Expedition as well as a bestselling book about the voyage, Farthest North.

Marriages and Children

On 6 September 1889, Fridtjof Nansen married Eva Sars (1858–1907), a mezzo-soprano and skier who was one of the first female Norwegian ski jumpers. They had five children: Liv (1893–1959), Kaare (1897–1960), Irmelin (1900–77), Odd (1901–73), and Asmund (1903–13). Nansen married his second wife Sigrund Munthe (1869–1957) in 1919.

Diplomatic Career

Fridtjof Nansen played a crucial role in Norway’s independence from the Swedish Crown in 1905, persuading Prince Charles of Denmark to accept the Norwegian throne as King Haakon VII. From 1906 to 1908, Nansen served as Norway’s ambassador to the United Kingdom. Norway remained neutral during the First World War, and Nansen led a Norwegian delegation to the United States in 1917 to negotiate the shipment of essential foodstuffs through the allied blockade.

Humanitarian Work

In 1920, Fridtjof Nansen became one of the founding delegates in the League of Nations, in charge of repatriating prisoners from the First World War. In 1921, he organized European relief efforts through the Red Cross and Save the Children during the Russian famine of 1921–22. In 1922, Nansen became the first League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. That year, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for "for his leading role in the repatriation of prisoners of war." He had helped more than 400,000 prisoners to return home.

In 1922, at the Council of the League of Nations, Nansen proposed the creation of a document that would allow refugees from the First World War, Russian Civil War and Armenian genocide to cross borders and receive protection from deportation. The Nansen passport for stateless citizens was issued to approximately 450,000 refugees around the world between 1922 and 1938 and recognized by 52 countries. Canada, however, refused to ratify the Nansen passport in the 1920s because the Canadian Department of External Affairs wanted to retain the right to return refugees to their country of origin. In this case, Canada followed the example of the United States (a nation that did not join the League of Nations) rather than the United Kingdom.

Later Life

During his last years, Fridtjof Nansen was the head of a League of Nations delegation charged with finding a safe homeland for Armenian refugees from the former Ottoman and Russian Empires. Armenian refugees were issued Nansen passports, and 7,000 of them were resettled in Soviet Armenia.

Nansen died of a heart attack at his home, Polhogda, at the age of 68.

Legacy

Fridtjof Nansen’s achievements inspired other polar explorers, including Otto Sverdrup, Roald Amundsen, Henrik Larsen, Robert Peary and Ernest Shackleton. Nansen’s home, Polhogda, is now the Fridtjof Nansen institute (FNI), a research foundation specializing in international environmental, energy and resource management politics and law. The FNI collaborates with Canada and the Arctic Council.

Nansen’s inventions continued to be in use long after his death, including the Nansen Bottle for collecting ocean water samples at specific depths and the wooden Nansen sledge on ski runners that he developed in Greenland based on Inuit designs. The Nansen sled was used by Geological Survey of Canada glaciologist Roy Koerner during his ice core studies in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) established the Nansen Refugee Award in 1954 to honour individuals, groups and organizations who have taken extraordinary action to protect refugees as well as internally displaced and stateless people. The people of Canada received the Nansen Award in 1986.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom