Garden River First Nation refers to both an Anishinaabe community and a reserve. The reserve, legally known as Garden River 14, consists of over 20,700 hectares of land, located along the St. Mary’s River in Ontario (see also Reserves in Ontario; First Nations in Ontario). The community and reserve are named after a tributary of the St. Mary’s River. The Anishinaabe planted gardens at the mouth of the tributary. As of September 2024, Garden River has a total registered population of 3,558 people, with 2,234 residing off reserve. It is governed by an elected Chief and council under the terms of the First Nations Elections Act.

History

Officially, Garden River First Nation reserve was created with the signing of the 1850 Robinson-Huron Treaty and demarcated in an 1852 survey. Although the history of the reserve may have technically begun in 1850, the Anishinaabe presence in the region stretches back millennia. For many generations, the mouths of the various tributaries that fed the St. Mary’s River served as places to grow crops, such as corn and beans. The various tributaries, including the Garden River, also served as access points for family hunting territories generally located upstream. French missionaries called the area Rivière au Désert which was translated to Garden River by English speakers. These names derived from the Anishinaabe name for the area, Ketegaunseebee.

Anglican and Catholic missionaries established a presence at Garden River by the early 1840s. Initially, the missions were located in Sault Ste Marie until the Anishinaabe relocated to the Garden, Root and Echo Rivers post-1838, where their gardens were located. The move was undertaken to distance the community from Métis liquor dealers, find space to grow crops and live at arm’s length from Indian agents and missionaries. Additionally, Chief Shingwaukonse planned to develop an Ojibwe homeland at Garden River for the Great Lakes Anishinaabe. The United States and British-Canadian government policies ensured that the homeland would not be created. Shingwaukonse’s vision for an Anishinaabe homeland also contained the idea for a ‘Teaching Wigwam’ where Anishinaabe and European knowledge would be taught. This portion of the vision, continued by his son Ogista, was transformed into the Shingwauk Residential School in 1871 (see also Residential Schools in Canada).

In 1849, Shingwaukonse and two other chiefs led a group of Anishinaabe and Métis to the copper mine at Mica Bay on Lake Superior (see Mica Bay Incident). This event was undertaken in response to British-Canadian governmental failure and seeming unwillingness to undertake a treaty that would allow mining, other resource extraction and settlement. Ultimately, this led to the signing of the Robinson-Huron and Robinson-Superior Treaties in 1850 (see Robinson Treaties of 1850). The Chiefs surrendered a tract of land stretching from "Penetanguishene to Sault Ste Marie, and thence to Batchewanaung Bay on the northern shore of Lake Superior; together with the islands." Garden River was included within the treaty’s schedule of reserves. Garden River reserve lost two-thirds of its original treaty area under the 1859 Pennefather Treaty. Other surrenders, leases and right-of-ways eroded Garden River’s land base from the 1860s to the 1960s. For instance, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), in 1897, acquired lands for a station and ballast pit. The CPR ballast pit was subsequently expanded in 1912 and again in 1914. In 1850, the reserve was approximately 52,600 hectares. After numerous treaties and land appropriations, the size of the reserve was reduced to approximately 12,950 hectares by 1989.

Garden River has consistently defended its rights to the land, specifically those guaranteed under treaty. Since at least the 1970s, after the renewal of the land claim process under Prime Minister Pierre E. Trudeau, the Chief and Council of Garden River First Nation have sought to rectify concerns surrounding the 1852 reserve boundary survey, 1859 lands surrender, various right-of-ways, railway ballast pits and other surrenders. For instance, from the 1970s until the early 1990s, negotiations for the return of the lands surrendered in 1859 and the highway right-of-way were paramount. Some of these issues were resolved in July 1994 under the Lands and Highway Settlement, which returned approximately 10,500 hectares of land. Additionally, this agreement led to the Trans-Canada Highway 17 bypass, which relocated the main highway from the centre of the community. In 2010, following disputes with the provincial government over the Harmonized Sales Tax, Garden River indicated it would implement tolls on Highway 17. This led to backlash by some residents and vandalism of the public notices posted at the edge of the reserve, some of which included racist statements.

Also in 2010, as part of the Robinson-Huron Treaty Litigation Fund, Garden River sought compensation from both the provincial and federal governments for their failure to abide by the annuity terms of the 1850 treaty. In 2023, the Fund agreed to $10 billion in compensation, to be divided amongst the 21 First Nations in 2024. Garden River and Atikameksheng Anishnawbek are pursuing a court application against the lawyers for the Fund. The application claims that the lawyers’ fees are excessive and wants the courts to reduce them. Lastly, the Fund and its lawyers are continuing to negotiate for an increase in individual annuities for all signatory nations.

Garden River has also served as a key site for Anishinaabe politics. Shingwaukonse, recognized by the British as the leader of the Anishinaabe from Lake Huron to Lake Superior, led treaty negotiations in 1850 that were meant to protect Anishinaabe lands and people. In 1919, Fred O. Loft, hosted by Garden River, spoke in Sault Ste Marie about the need for a united organization for First Nations in Canada, known as the League of Indians (see also Indigenous Political Organizations and Activism in Canada). Garden River leaders were often outspoken during the Grand General Indian Council of Ontario meetings from 1870 to 1936. In 1928, the Council met at Garden River to discuss the Indian Act and other concerns. More recently, Garden River acts as a hub for revitalizing Anishinaabe culture, language, spirituality and sovereignty (see also Anishinaabemowin: Ojibwe Language). During his lifetime, Dan Pine was a healer and traditionalist. He was also known for his work in promoting and defending Anishinaabe rights across Turtle Island.

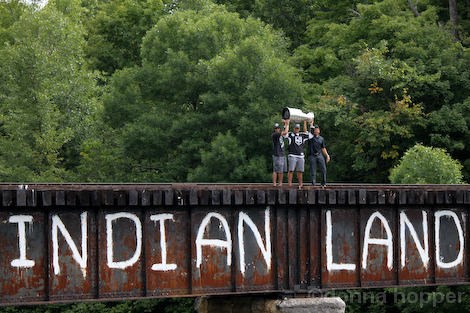

In 1973, Bob, Darrell, Keith and Willie Boissoneau, along with Andre and Scott Lesage painted ‘This is Indian Land’ on the Garden River train bridge. The action, meant as an act of political resistance, is a simple and bold statement that everyone is on Indigenous land (see also Indigenous Territory). The bridge is considered iconic among First Nations across Turtle Island. Indigenous and non-Indigenous people stop and take pictures of and selfies with the bridge.

Economy

Government services through the First Nation’s Band Office are a major employer on Garden River reserve. Nevertheless, there are a number of notable businesses in and around the community not affiliated with the band office, such as Bell’s Point Campgrounds, Family Tree-Native Crafts, Big Arrow Variety, Perreault’s Gas Station, Turtle Concepts and Smoke Signal’s, as well as various forestry or logging operations. Additionally, the Anishinabek Police Services headquarters are located in the community. Many people also work off-reserve in the nearby communities of Echo Bay or Sault Ste Marie.

Culture

Between 1900 and 1969, and again from 2006 to 2008, Garden River performed the Hiawatha Play, which was derived from Henry W. Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha. This play was in turn loosely based on stories collected from the Anishinaabe and published by H. R. Schoolcraft. The first performance of the play was held during Alice Longfellow’s trip to the region in 1900. Alice Longfellow was the daughter of Henry W. Longfellow. Initially performed in Desbarats, Ontario, the play was moved to Garden River. During its run, the Hiawatha Play was also performed in Sault Ste Marie (Ontario and Michigan), Toronto, Montreal, Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh and Plattsburg in North America, as well as in London, Portsmouth, Amsterdam and Antwerp in Europe. From 1900 to 1969, performances were undertaken in Anishinaabemowin with a mix of stereotypical costuming, such as Plains-style headdresses, and cultural items from Garden River, such as Shingwaukonse’s pipe and treaty medals. The performances from 2006 to 2008 were largely conducted in English and generally derived from the original script, drawing heavily from contemporary experiences and stories. In addition to the Hiawatha performances, the Garden River actors undertook other cultural and ‘historic’ plays to celebrate local history. These performances were about entertaining tourists from across North America and Europe while exhibiting Anishinaabe culture, language and pride in being Indigenous.

Today, Garden River is better recognized as the home of well-known sports figures including former National Hockey League (NHL) coach Ted Nolan, former NHL players and Shoresy actors Jordan and Brandon Nolan and fastball pitcher Darren Zack. Well-known spiritual figures include Shingwaukonse and Dan Pine. Important cultural figures include author Lesley Belleau, storyteller and actor Dillan Chiblow and carver Phil Jones. The Dan Pine Healing Lodge is also nationally known and respected as a traditional spiritual and healing centre.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom