Human beings have practised birth control throughout history. However, in 19th-century Canada, this practice was largely forbidden or taboo. It was only in the 1920s that groups of citizens formed to defend birth control. The information, services and products related to this practice became increasingly accessible after the war. During the 1960s, Canada decriminalized contraception and abortion. In the 1970s, the number of organizations and services promoting access to contraception and family planning began to increase. From then on, birth control became an integral part of the public health approach to sexual health.

Beginnings

Throughout history, people have limited the number of births using various methods. These included abstinence, prolonged breastfeeding, pessaries, and abortion-inducing potions. Prior to the colonists’ arrival in Canada, the Indigenous peoples used certain plants to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. Among the colonists, the traditional midwives did the same. In New France, families had seven or eight children during the 17th century and four to six during the 18th. The last third of the 19th century saw the advent of the large French-Canadian families with 10 or more children, a phenomenon based on ethnocultural and religious beliefs.

In 1869, two years after Confederation, Canada passed a law making abortion illegal. In 1892, the first Criminal Code also criminalized both the distribution and sale of contraceptive products and the dissemination of information regarding these products. If the accused could not prove that they were acting for the “public good,” they could be sent to prison for two years. This was why women hid their pregnancies for as long as possible, fearing that they could miscarry and be wrongly accused of having induced an abortion.

The term “birth control” was first used in 1914 and meant the deliberate prevention of conception using mechanical or chemical methods.

Leading Advocates

Prior to the First World War (WWI), some Canadians advocated birth control for health reasons. During the 1920s, groups formed in support of this approach. Following the example of similar groups in Great Britain and the United States, they maintained that a child should be wanted and raised properly. Birth control would allow women to prevent unwanted, annual pregnancies and would reduce the number of illegal abortions. It would help improve marital relationships, as well as the health of mothers and children and the well-being of the family. However, these groups did not go so far as to claim that birth control was the cure for social problems due to poverty.

These groups were generally made up of educated men and women, primarily Protestant anglophones. Some members drew inspiration from the Social Gospel movement, while others were feminists. They came from every walk of life and their political views ranged from socialism to conservatism. Among French-Canadians, religious teachings and public policy dictated that women become pregnant on a regular basis. At the same time, pro-natalist pressure groups from the business, religious and political communities were opposed to birth control. Their attacks against birth control advocates were frequent and often defamatory.

Nevertheless, during the 1920s, research conducted globally in the field of human sexuality generated interest in Canada. The 1892 legislation was challenged and the size of affluent families decreased. Well-informed couples were able to secretly procure commercial contraceptives or resort to more creative measures. However, the pregnancy rate among the disadvantaged classes remained high and the supporters of birth control brought pressure to bear to make contraceptive methods free to everyone who wanted to use them.

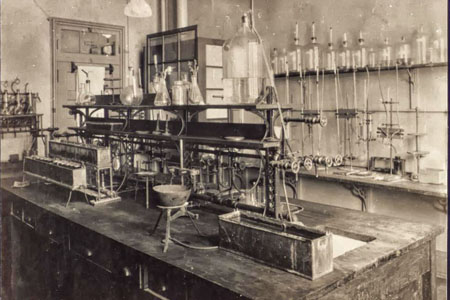

To avoid the issue, the politicians invoked the law. Meanwhile, a very small number of volunteer groups resolutely directed women toward a few courageous doctors or gave information to married women. The first Canadian pro-contraception group was created in Vancouver in 1923. The first birth control clinic opened in Hamilton in 1932, under the leadership of Elizabeth Bagshaw.

Initial Programs

As early as 1930, a birth control program was offered to low-income women by A.R. Kaufman, a philanthropist from Kitchener, Ontario. His parental information office, the Parents’ Information Bureau (PIB), sent contraceptives by mail to families requesting them or arranged consultations with doctors prepared to provide them with diaphragms or to carry out sterilization procedures.

Did you know?

A.R. Kaufman believed in eugenics. He saw contraceptives and sterilization as methods of controlling the demography of the working class, who he deemed “unintelligent” and prone to producing “feeble-minded” children. The same beliefs in eugenics were at the root of the forced sterilization of Indigenous women in the early 20th century. (See Sterilization of Indigenous Women in Canada.)

In 1936, an employee of the PIB, Dorothea Palmer, was arrested and accused of disseminating birth control information and distributing contraceptive materials in a predominantly francophone disadvantaged suburb of Ottawa. Her lawyers obtained her acquittal by pointing out that she was not trying to make a profit, but was acting “for the public good.” The case set a jurisprudential precedent and reassured many other groups advocating birth control.

After the Second World War (WWII) and the baby boom which followed, public opinion became increasingly favourable regarding birth control. In 1955, Rita and Gilles Breault created the Service de régulation des naissances (Serena) in Lachine, Quebec, in order to raise awareness regarding the symptothermal method, a natural method of birth control. Established by lay people, Serena was in keeping with Catholic moral teachings and advocated a primarily Christian view of birth control. The subsequent availability of the birth control pill and intrauterine devices (IUDs), as well as an increasing awareness of the “population explosion,” led to the creation of new volunteer birth control groups.

In 1963, Barbara and George Cadbury, passionate supporters of birth control, established a Canadian federation which brought together the birth control associations in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Hamilton, Toronto and Ottawa. They were successful in having their federation become part of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF). The objectives of the Canadian federation were to empower parents and to inform the public. New groups from Edmonton, Montreal and Calgary also agreed to join it.

The Canadian federation was initially called the Canadian Federation of Societies for Population Planning. In 1967, it was called the Canadian Federation for Family Planning and, in 1975, it became the Planned Parenthood Federation of Canada (PPFC). Some groups in the Vancouver and Winnipeg regions received subsidies from the United Way. From 1967, the Quebec government subsidized the training of francophone specialists and social workers, as well as the Serena organization. In 1969, the government of British Columbia provided subsidies to the province’s Planned Parenthood Association (now known as Options for Sexual Health).

Decriminalization and Developing Programs

During the 1960s, the New Democratic Member of Parliament Robert W. Prittie brought the cause of decriminalizing birth control before Parliament. With unofficial support from the Anglican, Presbyterian, United and Unitarian churches and, later, from the Canadian Home Economics Association and the Salvation Army, the Planned Parenthood Federation of Canada (PPFC) lobbied the federal government to have birth control removed from the Criminal Code. The Canadian Medical Association and other voluntary organizations supported this action. As the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops stated that it was not opposed to the amendment, the law was changed in 1969 under BillC-150, which also decriminalized therapeutic abortion. This relaxation of the 1869 legislation triggered a social crisis which once again raised the thorny issue of birth control and, more specifically, of abortion.

Abortion, now considered a medically necessary health service, was not decriminalized by the Canadian government until 1988. Dr. Henry Morgentaler, accused on a number of occasions of performing abortions, contested the government’s right to prohibit abortion services in Canada. Prior to 1988, the Criminal Code had been invoked to prosecute physicians and other individuals who performed voluntary terminations of pregnancy.

Chronology of Bills to Amend the Criminal Code from 1955 to 1969

1 April 1955: As part of the overhaul of the Criminal Code, the legislature removes the word “illegally” in Section 237 (regarding abortion), which led to a great deal of controversy; physicians feared being convicted even if the abortion was performed for therapeutic reasons. The legislation would remain unchanged until 1969.

10 June 1960: The Canadian government authorizes the sale of the birth control pill solely if its use is intended to regulate the menstrual cycle. Using it for the purposes of birth control remains a criminal act.

15 October 1964: Bill C-48, intended to amend Section 150 of the Criminal Code to allow the dissemination of information regarding birth control and the sale of contraceptives, is introduced.

1 March 1966: The Standing Committee on Health and Welfare begins the reading of private bills C-22, C-40, C-64 and C-71, which are intended to amend the legislation with respect to the dissemination of information regarding birth control and the sale of contraceptives.

3 October 1967: The Standing Committee on Health and Welfare begins studying Bills C-122, C-136 and C-123 as they relate to Sections 237 and 238 regarding abortion.

21 December 1967: Pierre Elliott Trudeau, minister of justice at the time, introduces Bill C-195, proposing numerous amendments to the Criminal Code, notably with respect to abortion.

13 March 1968: Bill C-195 dies on the Order Paper.

19 December 1968: Bill C-150 is introduced. It is almost identical to Bill C-195.

April-May 1969: Bill C-150 is hotly debated in Parliament.

14 May 1969: Bill C-150, amending the Criminal Code and legalizing abortion for therapeutic reasons, is passed on the third reading.

In 1971, the PPFC, subsidized by the Department of National Health and Welfare (known today as Health Canada), decided to act as a catalyst to encourage the government to fund the costs related to birth control information and services throughout Canada. The number of organizations championing the cause or offering their services increased and some provincial governments began offering programs. The PPFC also raised money for the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF).

In 1972, the Department created the Planned Parenthood Funding Program to help the organizations expand their services. From 1972 to 1974, the subsidies awarded to the PPFC and Serena represented, on average, 50.6 per cent of the program’s funds. Birth control education and services became a political issue and, from the 1970s, various public and private programs were introduced to help provide these services. In 2005, the Planned Parenthood Federation of Canada became known as the Canadian Federation for Sexual Health (CFSH), in order to more clearly reflect its goals. The government no longer provided funds to non-profit organizations like Serena and the CFSH.

The Canadian government began responding to requests for aid to developing countries and awarded subsidies to the IPPF and to the United Nations Population Fund for birth control activities.(See also United Nations.) This international aid for birth control is ongoing. Serena is also holding discussions with similar groups abroad, notably in France.

Various groups and government agencies have assumed the responsibility for informing Canadians of the benefits of information regarding pregnancy and responsible sexual behaviour. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) disseminates readily accessible, factual information regarding reproduction and sexuality. The information is designed to be accessible to all Canadians, regardless of their ethnic, cultural or religious background. The mandate of the PHAC is to develop effective, inclusive teaching methods regarding sexual health. In 1994, it designed the first Canadian Guidelines for Sexual Health Education, which were revised in 2003, 2008 and 2019. The amount of easily accessible public information regarding sexuality and birth control has increased substantially since the end of the 20th century, particularly with the availability of Internet services.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom