The music's commercial beginnings, which are of greater relevance to its history in Canada, are usually dated from 1917 — specifically to the recordings (including one of Shelton Brooks's “Darktown Strutters' Ball”) by a white New Orleans quintet, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band.

Since then, jazz has undergone constant and often dramatic change. It has followed several parallel courses and overlapping styles, at times in response to external influences (e.g., those of chamber and symphonic music in the “third stream” of the 1950s, and of rock and R&B in the fusion style originating in the late 1960s), but more often due to internal innovation and transformation. While jazz has exerted a marked influence on other genres of music during its first 100 years, it has itself undergone a degree of internationalization as musicians of other countries, Canada early among them, have taken up, adopted and/or adapted many of its traditions.

By the early 21st century, jazz increasingly found a place on the curricula of many universities and colleges in Canada and elsewhere, but its tradition remains largely aural. It has been assimilated most often by imitation of admired, iconic performers (e.g., Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, etc.), followed by selective refinement of what has been imitated and, finally, evolution into a personal style or form of self-expression.

Four Canadian musicians have moved decisively into this category of admired icon, whereby they have influenced the tradition's larger development or been imitated in turn. Oscar Peterson is widely recognized as one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time, and among the most influential of the postwar era. Paul Bley was a significant figure in the free jazz movement of the early 1960s, and his trios were a model for many American, European and Canadian pianists. The trumpeter Kenny Wheeler developed a distinctive compositional style and lyrical approach to his instrument that have been widely imitated. While initially known as a jazz pianist, Diana Krall introduced jazz to broader audiences and was among the most commercially successful vocalists in any musical genre in the early 2000s.

Other Canadians, such as Ed Bickert, Sonny Greenwich, Claude Ranger, Fred Stone, and Nelson Symonds, Barry Elmes, Al Henderson, Jean Derome, Brad Turner and Phil Nimmons, established local traditions in their respective cities and rivalled the admired US musicians as formative influences on later generations of Canadian players.

Early History in Canada

The earliest jazz musicians in Canada were of American origin and appeared on vaudeville stages and in cabarets in the mid-to-late 1910s. The Original Creole Orchestra, a New Orleans ensemble that included the cornetist Freddie Keppard, toured the Pantages circuit in Western Canada in 1914 and 1916, and Jelly Roll Morton performed in Vancouver cabarets as early as 1919 and as late as 1921. By then, the American pianists James “Slap Rags” White and Millard Thomas had settled in Montréal, where the size and concentration of the city's Black population in St-Henri led to the development of a thriving entertainment scene over the next 35 years (see also Black Music and Musicians in Canada).

Scant evidence survives of the first Canadian jazz bands and musicians. The discographer Jack Litchfield has identified the pianist Harry Thomas as Canada's earliest jazz musician on the basis of the improvisational content of Thomas' ragtime recordings from 1916.

Many Canadian dance, “novelty” or “syncopation” bands in the early- and mid-1920s included American jazz hits of the day as part of broader repertoires. The Gilbert Watson Orchestra of Toronto featured the American trumpeter Curtis Little among its soloists, and included a version of St. Louis Blues among its several 78s made in 1925 and 1926, likely the first by a Canadian band recorded in Canada. Millard Thomas and His Chicago Novelty Orchestra recorded in Montréal in 1924 during a nine-year sojourn in that city. Also in 1924, Guy Lombardo recorded in Richmond, IN, with His Royal Canadians, and in London, ON with his New Princes' Toronto Band. Both records show the influence of jazz.

Musicians in Canada with the improvisatory skills required of the “hot” soloist also included cornetist Jimmy “Trump” Davidson, trombonist Seymour “Red” Ginzler and saxophonist Cliff McKay in Toronto, saxophonists Charlie See and Chick Inge in Vancouver, and saxophonist Adrien “Eddy” Paradis and several American musicians (e.g., the Johnson and Shorter brothers) in Montréal.

Following Millard Thomas's lead, other Black musicians from the US and Canada formed bands during the 1930s, including the saxophonist Myron Sutton (The Canadian Ambassadors), the trumpeter Jimmy Jones (Harlem Dukes of Rhythm) and the drummer Eddie Perkins in Montréal, and the pianist Harry Lucas (Harlem Aces) in Toronto.

Jazz remained an incidental part of Canadian popular music from the 1930s to the 1940s, though several key musicians sustained the form in various regions: McKay, Trump Davidson, Ted Davidson, Bobby Gimby, Bert Niosi, and Pat Riccio in Toronto; Paradis, violinist Willy Girard, pianist Bob Langlois and saxophonist Stan Wood in Montréal; and saxophonist Carl “Beaky” DeSantis, guitarist Ray Norris, and pianists Bud Henderson and Wilf Wylie in Vancouver.

Visiting American big bands in both jazz and swing styles, however, appeared frequently in Canadian dance halls and recordings, and live broadcasts on US radio could be heard in Canada. Bob Smith began to broadcast recordings on CJOR Vancouver as early as 1937, and Byng Whitteker and Elwood Glover were heard by 1941 in Toronto on the CBC's 1010 Swing Club. CBC Radio broadcasts of Oscar Peterson performing in Montréal in the mid-1940s were instrumental in establishing him as Canada's first jazz star.

Traditional and Dixieland

The popularity during the 1940s of two small-band idioms — a revival of traditional New Orleans music and the new style known as bebop — had a pivotal effect on the development of jazz in Canada. Incompatible with the more commercial settings in which jazz previously had been heard, “trad” and bop required its musicians to assert their own autonomy.

Both the traditional music of African Americans in New Orleans and the Dixieland of their white imitators had proponents in many Canadian cities. The concentration of activity in these styles, however, was in Toronto, beginning in the mid-1930s when Trump Davidson's dance band showed a decided Dixieland influence. The international “trad” revival was taken up in Toronto in the late 1940s by Clyde Clarke (pianist and leader of the Queen City Jazz Band, and also a scriptwriter for CJBC's 1010 Swing Club), Ken Dean (cornetist and leader of the Hot Seven) and Michael Snow, among others.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the leading Toronto band was cornetist Mike White's Imperial Jazz Band, which often presented American players as guest soloists. Other popular bands were led by Jimmy Scott and trombonist Bud Hill. The Metro Stompers (led in turn by the bassist Jim McHarg and Jim Galloway) were the most successful band of the mid-1960s (rivalled by Larry Dubin's Big Muddys) and survived through the 1970s before turning to a mainstream, swing style in the 1980s. The Stompers were eventually supplanted as local favourites by the Climax Jazz Band, formed in 1971.

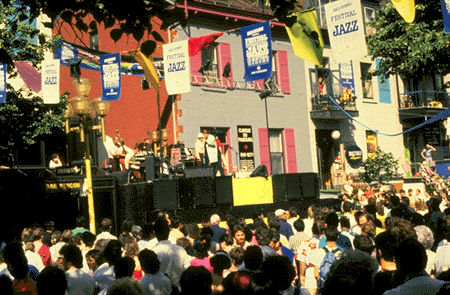

Other cities also had bands or musicians who championed “trad” or Dixieland: Lance Harrison in Vancouver, beginning in 1950; cornetist Peter Power in Halifax during the 1950s; pianist Gordon Bennett's Capital City Jazz Band, formed in Ottawa in the 1950s and rivalled in the early 1980s by the Apex Jazz Band; the Limestone City Jazz Band (late 1950s to early 1960s) in Kingston, ON; and trumpeter Russ Meredith (1940s and early 1950s), the Mountain City Jazz Band (1950s and early 1960s) and the Al Peters Jazz Band (1970s) in Montréal. A younger generation of players was heard in Montréal during the 1980s playing in such groups as Bande à Magoo, Dixieband and Sweet Dixie as part of the street activities of the Festival international de jazz de Montréal (FIJM).

Many veteran “trad” and Dixieland musicians in Toronto are of British or European origin, and include a large contingent of Scottish players, among them Galloway, McHarg, the trombonist Jim Abercrombie (leader of the Vintage Jazz Band), the cornetist Charlie Gall (leader of Dr McJazz), the trumpeter Malcolm Higgins, the clarinetist Al Lawrie (leader of the mainstream Jazz Corporation that also includes the pianist Ian Bargh) and the clarinetist Jim Purdie. The London-born trumpeter Cliff “'Kid” Bastien (leader of the Black Eagle, Magnolia and Camelia jazz bands, as well as the Happy Pals) was influential in the development of many traditional musicians who would later lead their own bands, most notably drummer Dennis Elder of the Silver Leaf Jazz Men, established in 1974.

Bebop

Developed in New York in the early 1940s and first documented on commercial recordings in 1944, this harmonically advanced, rhythmically freer and assertively virtuosic style of jazz made its way to Canada by the late 1940s, as recordings by Moe Koffman and Oscar Peterson attest. Other Canadian “boppers” in the 1940s included: Paul Bley, Willy Girard, pianist Sadik Hakim (an American musician active in Montréal 1949–50 and 1966–76), tenor saxophonist Benny Winestone, pianist Harold “Steep” Wade, trombonist Jiro “Butch” Watanabe, and drummers Billy Graham and Mark “Wilkie” Wilkinson in Montréal; Al Neil and Ray Norris in Vancouver; Herb Spanier on the Prairies; and Norm Amadio, tenor saxophonists Bill Goddard and Dave Hammer, and trumpeter Graham Topping in Toronto.

Bebop remained fundamental to the styles of most of Canada's popular jazz musicians for the next 30 years. The so-called “west coast cool” style, which postdates bebop by about five years but attracted some of its players, was perpetuated in Canada in the mid-1950s by bands led by Ron Collier and Fraser MacPherson, in the 1980s by Rob McConnell, and in the arrangements of Phil Nimmons and other big band writers.

Other notable stylists in the bop tradition included: pianists Wray Downes, Mark Eisenman, Hakim and Maury Kaye; drummers Pete Magadini and Norman Marshall Villeneuve; alto saxophonists Sayyd Abdul Al-Khabyyr, Dale Hillary, Bob Mover, Alvinn Pall, Leo Perron, Bernie Piltch, P.J. Perry, Campbell Ryga and Dave Turner; flutist Bill McBirnie; trumpeter Kevin Dean, and American trumpeters Charles Ellison and Sam Noto (the former in Montréal, the latter intermittently a resident of Toronto after 1975).

Big Bands

The first Canadian big band — 12 to 21 musicians divided into brass, reed and rhythm sections — known to have had an extensive jazz repertoire was the Rex Battle band of Toronto. The band worked in the summer of 1935 at Bob-Lo Island, near Detroit, and was patterned after Bob Crosby's US band. Bert Niosi, Trump Davidson, Cy McLean and Johnny Holmes led dance bands with some jazz leanings during the 1930s or 1940s. However, it was not until the 1950s and the formation of bands by Calvin Jackson, Phil Nimmons and Graham Topping in Toronto, Steve Garrick and “Butch” Watanabe in Montréal, and Dave Robbins in Vancouver that the big band tradition was established firmly in Canadian music. Other bands followed in the 1960s, including those led by trombonist Ray Sikora in Vancouver, by Ron Collier, Pat Riccio and Don Thompson in Toronto, and by Lee Gagnon and Vic Vogel in Montréal.

The rise of the stage band movement in Canadian schools in the early 1970s led to both a growing audience and a new supply of musicians for big bands (with which stage bands share the same instrumentation and repertoire). The Canadian Stage Band Festival (now MusicFest Canada) has been the focus for this activity, and Humber College in Toronto was initially its academic centre. Though essentially student ensembles, three Humber College bands — the “A” and “B” bands, and Ron Collier's Humber Extension — were among the leading big bands in Canada in the late 1970s, rivalled by bands from several other schools beginning in the 1980s.

Other important bands in this period were led by Hugh Fraser, Bob Hales, Doug Parker and Fred Stride (Westcoast Jazz Orchestra) in Vancouver; Tommy Banks and Bob Stroup in Edmonton; Eric Friedenberg (Saturday Pro Band) in Calgary; Kerry Kluner and Ron Paley in Winnipeg; Jim Ahrens (Tribal Unit), Shelly Berger, Jim Galloway (Wee Big Band), Jim Howard, Russ Little, Rob McConnell (Boss Brass), Dave McMurdo, Ted Moses, Brigham Phillips and Fred Stone in Toronto; and Denny Christianson and Andrew Homzy in Montréal.

The format underwent a resurgence in the 1990s with the Neufeld-Occhipinti Orchestra (NOJO; formed in Toronto by pianist Paul Neufeld and guitarist Michael Occhipinti), which frequently featured American guest soloists such as Sam Rivers and Don Byron, and Vancouver’s Hard Rubber Orchestra and New Orchestra Workshop (NOW) Orchestra, the latter of which included vocalist Kate Hammett-Vaughan as an integral component.

In 2005, Vancouver native Darcy James Argue formed the Brooklyn, NY-based Secret Society, which drew on the “steampunk” movement and the influence of arranger-trombonist Bob Brookmeyer, and employed a number of Canadian expatriates including trumpeter Ingrid Jensen and pianist Gordon Webster. In Montréal, saxophonist Christine Jensen formed a big band in 2010; and in 2012, she created the Orchestre National de Jazz de Montréal in conjunction with pianist Marianne Trudel, Andrew Homzy and others.

Variants on the big-band format have included Doug Hamilton's Brass Connection (five trombones plus rhythm section) formed in 1979 in Toronto; the Alberta Jazz Repertory Orchestra, active under a succession of leaders in Edmonton during the mid-1980s; the Toronto new-music/jazz orchestra Hemispheres; and large, free-improvisational ensembles directed by Jean Derome in Montréal (la G.U.M.) and Fred Stone in Toronto.

See also: Dance bands.

Third Stream

This term, introduced in the mid-1950s by the American composer-conductor Gunther Schuller, describes a style that combines elements of classical music (usually form) with those of jazz (improvisation, rhythmic character and tonal colour). The third stream movement flourished in Canada concurrently with activity elsewhere, largely through the efforts of Norman Symonds, Ron Collier and other pupils of Gordon Delamont, all of whom employed fugue, sonata, concerto grosso and other forms as frameworks for improvisation by jazz groups.

Writing in the Dictionary of Contemporary Music about Symonds's Concerto Grosso for jazz quintet and symphony orchestra (1957), John Beckwith described the work as “more natural than such parallel European works as those of Rolf Liebermann, in which the jazz element is more superficially imitated and more crudely contrasted with the concert-symphonic vocabulary.” Symonds continued to work in the idiom throughout the 1960s and completed several works for orchestra and jazz soloist, or jazz group.

Also in the 1960s, the Dave Robbins big band and the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra united for performances of works in this idiom, among them several by Robbins's bassist, Paul Ruhland. A similar collaboration in 1984 found the Boss Brass and the Toronto Philharmonic in a program of commissioned works byLouis Applebaum, Victor Davies, Harry Freedman, Rob McConnell, Ian McDougall, and Rick Wilkins.

Ron Paley wrote and, with his trio or big band, premiered four works with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra (1979–87); Ian Sadler led the Alberta Jazz Repertory Orchestra in a program of original compositions at Jazz City in 1982; and Tim Brady (who has composed in both jazz and new-music idioms) completed Visions, recorded with Kenny Wheeler in 1985. Brady subsequently produced a number of recordings featuring symphonic orchestration and multi-tracked guitar. Vancouver-based clarinetist François Houle — classically trained at McGill University and Yale University, but heavily influenced by jazz musicians Steve Lacy and John Carter — moved readily between forms with his own electro-acoustic recordings, a chamber quintet and the ensemble Standing Wave.

Paul Ruhland, Doug Riley and Don (W.) Thompson have employed the 12-tone row in themes for jazz group or orchestra. Such jazz soloists as saxophonist Bernie Piltch and flugelhorn player Fred Stone (who himself wrote pieces in the third stream idiom) were central figures in the original movement, participating in several premieres (and later performances) of Canadian works. Works from the classical repertoire adapted for jazz group by Moe Koffman and Doug Riley, such as Moe Koffman Plays Bach (1971) and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (1972), enjoyed substantial commercial success in the 1970s. The influence of jazz is also evident in classical works composed by Freedman, Neil Chotem, François Morel, Michel Perrault, and John Weinzweig.

Contemporary

In the 1950s and 1960s, jazz began to move beyond the expanded harmonic framework and to break free of the rhythmic grids so thoroughly explored by bebop. The successive new developments represented by hard-bop, post-bop, modal jazz and other iterations came slowly to Canada, and were initially heard only in the music of Brian Barley, Sonny Greenwich, Lenny Breau, Claude Ranger and relatively few others, all of whom remained outside the conservative Canadian jazz establishment.

Most of the harmonic and rhythmic advancements in jazz were not fully embraced in Canada until the 1980s. Before then, they were championed without recognition by such musicians as Bob Brough, Alvinn Pall, Ron Park, Michael Stuart and John Tank. In the 1980s, the new approaches — as expressed by the iconic American saxophonist John Coltrane — became more commonplace in the music of a younger generation of musicians including Mike Allen, Ron Allen, Ralph Bowen, Patric Caird, Phil Dwyer, Rob Frayne, Kirk MacDonald, Mike Murley, John Nugent, Yannick Rieu, Mike Sim, Simon Stone, Perry White and Mike Zilber.

The influence of another significant American innovator, saxophonist Ornette Coleman, was also not felt until the early 1980s, and then largely through the work of Coleman's rock-influenced harmolodic band, Prime Time. This band was a model for several groups that emerged from Toronto's Queen Street West scene: Whitenoise, Not King Fudge and Noise R Us (all led by alto saxophonist and guitarist Bill Grove); Gotham City (led by saxophonist Nic Gotham); Malcolm Tent (led by trumpeter Jerry Berg); and N.O.M.A. (Northern Organic Musical Associations, led by trombonist Tom Walsh).

Conversely, the avant garde jazz of the 1960s and 1970s had Canadian protagonists almost immediately. The most prominent among them — pianist Paul Bley and trumpeter Kenny Wheeler — worked on an international level. As the bandleader who originally hired trumpeter Don Cherry and bassist Charlie Haden to accompany him at Los Angeles’ Hillcrest Club, Bley was instrumental in launching Ornette Coleman’s career. Bley next became a key member of clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre’s influential trio (with bassist Steve Swallow). Returning to the East Coast accompanied by his wife, composer Carla Bley, he helped form the Jazz Composers Guild, which featured important figures such as Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp and Roswell Rudd.

Wheeler, who moved to England in 1952, balanced his early career between working in mainstream bands and experimenting in live situations with members of London’s burgeoning free jazz scene, including John Stevens and Evan Parker. As a member of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble and the Globe Unity Orchestra, Wheeler helped develop a contemporary language for the trumpet in improvisational units.

Free jazz was introduced to Canada by the Artists' Jazz Band, formed in Toronto in 1962. The pianist and bassist Stuart Broomer led his first bands in Toronto in 1966, while Vancouver’s Al Neil turned from bebop to the new music around the same time. In Montréal, the Quatuor de jazz libre du Québec was founded in 1967.

After a period of relative inactivity, free jazz expanded on several fronts: in Montréal with the Atelier de musique expérimentale, active 1973–75, and the Ensemble de musique improvisée de Montréal, established in 1978; in Toronto with the CCMC and several ensembles led by Bill Smith; in London, ON, with the Nihilist Spasm Band and Eric Stach; in Calgary with Western Music Improvisation Co.; and in Vancouver with the New Orchestra Quintet, formed in 1977.

Originally a pianist, Jane Bunnett turned to soprano saxophone after developing tendonitis and quickly established herself as a distinctive voice — one who cleaved more closely to the sound of Steve Lacy, with whom she studied, rather than the dominant John Coltrane. In the 1980s, she moved onto the international scene with a series of recordings — In Dew Time, New York Duets, and Live At Sweet Basil — that showcased her talent alongside established US artists like pianist Don Pullen and saxophonist Dewey Redman.

Other individual musicians active in free jazz (or alternatively, free improvisation) included: pianists Broomer, Jean Beaudet, Paul Plimley, Michael Snow, Ajay Heble and Casey Sokol; saxophonists Smith, Stach, Maury Coles, Paul Cram, Bruce Freedman (Chief Feature), Nobuo Kubota (CCMC), Robert Leriche, Graham Ord (Free F'All, Garbo's Hat), John Oswald, Lori Freedman and Richard Underhill; violinist David Prentice; guitarists Eugene Chadbourne (a US musician active ca. 1973–76 in Calgary, where he also wrote music criticism for the Calgary Herald), Lloyd Garber, and Randy Hutton; bassists Lisle Ellis, George Koller, Clyde Reed and Claude Simard; and percussionists Roger Baird, Richard Bannard, Larry Dubin, John Heward, Claude Ranger, Jesse Stewart and Gregg Simpson. Ranger and Fred Stone have led important ensembles in this style.

As a relative term, “avant garde” also came in the 1980s to encompass the composed music of Tim Brady, the musique actuelle of Jean Derome, Justine, and René Lussier, the harmolodics of Not King Fudge and N.O.M.A., the orchestral music of Hemispheres and the free-fusion of Lunar Adventures.

While contemporary idioms continued to develop slowly in Canada, mainstream jazz, a melodic and emotionally moderate style that mixed the older swing and bebop traditions, enjoyed consistent popularity. Key Players included tenor saxophonist Eugene Amaro, Peter Appleyard, Ian Bargh, Guido Basso, Ed Bickert, Art Ellefson, Jim Galloway, Oliver Jones, Fraser MacPherson, Rob McConnell, tenor saxophonist Richard Parris, Oscar Peterson, tenor saxophonist Roy Reynolds, Joe Sealy, Brian Browne and Rick Wilkins, among others.

In the 1980s and 1990s — due to a combination of factors, including the increasing presence of Canadian jazz festivals and the development of post-secondary jazz education programs — a growing number of young musicians entered the jazz field. Several of them rose to prominence only after relocating to the US, including: pianists Andy Milne, Jon Ballantyne, John Stetch, Renee Rosnes and D.D. Jackson; trumpeter Ingrid Jensen; saxophonists Seamus Blake, Michael Blake, John Nugent and Andrew Rathbun; guitarist Kevin Breit; bassists Michael Bates and Chris Tarry; and drummers Harris Eisenstadt and Owen Howard.

Others remained in Canada and became influential linchpins in their local communities, including: in Vancouver, trumpeter Brad Turner, violinist Jesse Zubot, cellist Peggy Lee, guitarists Ron Samworth, Gordon Grdina and Tony Wilson, and drummer Dylan van der Schyff; in Toronto, trumpeters Kevin Turcotte and Lina Allemano, saxophonists Phil Dwyer and Kyle Brenders, guitarists Michael Occhipinti and Tim Posgate, bassists Kieran Overs, Andrew Downing and Roberto Occhipinti, and drummers Nick Fraser and Jean Martin; in Ottawa, saxophonist Rob Frayne, guitarist Roddy Ellias and bassist John Geggie; in Montréal, pianists Lorraine Desmarais, François Bourassa, Jeff Johnston, Steve Amireault and Marianne Trudel; trombonist Scott Thomson, saxophonists Christine Jensen and Joel Miller, guitarist Bernard Falaise, bassists Pierre Cartier and Normand Guilbeault, and drummer Pierre Tanguay.

The latter part of the 20th century also saw a number of US-born musicians begin to play important roles in building local or regional jazz scenes in Canada, including: bassist and educator Steve Kirby in Winnipeg; pianist, singer and journalist Bill King, and saxophonist and educator David Mott in Toronto; saxophonists Billy Robinson and Vernon Isaacs in Ottawa; and drummer and educator Jerry Granelli in Halifax.

Most significantly, after 1990, a distinctive Canadian compositional signature began to emerge, distinguished from music created in the US by that characteristic difference between Canadian and American societies: the expression of a multicultural mosaic as opposed to a melting pot. Primary examples among pianists alone included musicians such as John Stetch (who used elements from his Ukrainian heritage in his compositions), Marilyn Lerner (who integrated strains of Jewish klezmer music), D.D. Jackson (who referenced his mother’s Chinese background in equal measure to his father’s African-American heritage) and Andy Milne (who stood out among his fellow Black jazz musicians in New York City for his embrace of such Canadian folk artists as Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Bruce Cockburn — a reflection of his upbringing by his adoptive white family in Southern Ontario).

Fusion, Latin Jazz, World Beat

The “fusion” of the improvisational precepts of jazz with the technology (e.g., amplification, synthesizers, etc.), and rhythms of rock and R&B began in the mid-1960s in such US bands as Blood, Sweat and Tears (see David Clayton-Thomas). It was brought to a head by Miles Davis in 1969 and dispersed in several directions by his sidemen and others in the 1970s. Fusion, which also shows the influence of Latin music, was the most popular sub-style of jazz in the 1970s and 1980s. It was taken up by many bands and players in Canada beginning in the early 1970s with Pacific Salt in Vancouver, Maneige in Montréal, and the groups led by the American pianist and composer Ted Moses in Toronto.

Three bands dominated fusion music in Canada during the 1980s: Manteca, Skywalk, and UZEB. Skywalk and UZEB drew heavily on rock, Manteca on Latin and African rhythms, and all three employed the latest in synthesizer technology. Other notable fusion bands of the 1980s included Barclay Road, the Beards, Five After Four (led by drummer Vito Rezza), Mélosphere (led by violinist Helmut Lipsky), Northland (later, Nortlan), Orchestre Sympathique, Quartz, Purple Changes, Strangeness Beauty (see David Piltch), Synthetic Earth, Tasman, and the ensembles of Ron Allen, keyboard player Aaron Davis, guitarists Brian Hughes, Joey Goldstein, Sylvain Provost and Carlos Lopes, saxophonist Earl Seymour, violinist Hugh Marsh and drummer Mathieu Léger.

Fusion has been particularly popular in Québec, in part due to UZEB's compelling example. In the late 1980s, several musicians moved full circle and reintroduced more traditional elements of jazz into fusion, effectively creating a “post-fusion” style; among them in Canada were bassist Sylvain Gagnon, trumpeter John MacLeod, drummer Barry Romberg and the quintet Creatures of Habit.

In the late 1990s, fusion underwent a significant revivalist movement among younger musicians in New York City’s “Downtown” music scene. Concurrently, the cooperative Vancouver-based quartet Metalwood (consisting of Brad Turner, Mike Murley, Chris Tarry and Ian Froman) dominated the Juno Awards with consecutive recordings (1998–2004).

The fusion of Latin music with jazz predated that of rock with jazz by some 20 years. Jazz musicians began to employ Latin rhythms in the 1940s, and Latin bands have long featured jazz musicians in improvisatory roles. The Cuban singer Chicho Valle led Latin groups (e.g., Los Cubanos) in Toronto for 30 years, while jazz musicians organized Latin-oriented bands (i.e., jazz ensembles with expanded rhythm sections) on occasion in the 1960s (e.g., Émile “Cisco” Normand in Montréal) and 1970s (e.g., Guido Basso and the percussionist Marty Morell in Toronto).

In the late 1970s, Latin ensembles began to proliferate. The Columbian percussionist Guillermo Memo Acevedo introduced his Banda Brava, a salsa orchestra of variable size in Toronto, and became a leading figure in the development of Latin jazz in Canada. Other prominent bands in subsequent years included: in Toronto, Accento Latino, Coconut Groove and the Montuno Police (both led by percussionist Rick Lazar), Orquesta Fantasia and Ramiro Puerta's Ramiro's Orchestra; in Montréal, Arôma, Denis Fréchette Ad Lib, Québa, the Brazilian singer-guitarist Paulo Ramos, and the Brazilian percussionist Assar Santana and her band Chamel #6; in Winnipeg, percussionist Rodrigo Munoz's Papa Mambo and His Gringos; and in Vancouver, keyboard player Kathy Kidd's Afro Latin Sextet, the bands of guitarist Ray Piper and Salsa Ferreras (led by percussionist Salvador Ferreras).

The most significant advancement for Latin music in Canada occurred in 1982, when Toronto saxophonist Jane Bunnett and her trumpeter husband Larry Cramer visited Cuba. The trip shifted Bunnet’s musical focus away from contemporary jazz and toward an exploration of the diverse genres found on the island. Her subsequent trips to Cuba paved the way for a number of exceptional musicians — particularly pianists Hilario Duran and David Virelles, and drummer Dafnis Prieto — to make their way to Canada and eventually the US.

The emergence of world music, or “world beat,” as an influence on popular music in the late 1980s was personified in Canada by Ron Allen (playing the shakuhachi, a Japanese flute), Anoosh (led by the Armenian-Italian Raffi Niziblian), The Flying Bulgar Klezmer Band (later The Flying Bulgars), pianist and kora player Daniel Janke, singer El Kady (a.k.a. Ricardo Pellegrin of Guinea-Bissau), Mecca, pianist Lee Pui Ming and Space Trio, among others, who all combined elements of their respective (or adopted) folk traditions with jazz.

Vocalists

While vocalists historically have been among the most popular performers in jazz, few singers had high profiles in Canada prior to 1990. Eleanor Collins and Phyllis Marshall had pioneering careers on CBC Radio and TV during the 1940s and 1950s, and were followed most notably by Eve Adams, Salome Bey, Don Francks, Anne Marie Moss, Aura (a.k.a. Aura Rully), Arlene Smith and Eve Smith.

The Toronto-based pop-jazz vocalist Holly Cole enjoyed unprecedented popularity among Canadian jazz vocalists in the early 1990s with her albums Girl Talk (1990) and Blame It on My Youth (1992), both issued by the rock label Alert. Others active during this period in a variety of styles included David Blamires, Joanne Desforges, Trudy Desmond, Francks, Kate Hammett-Vaughan (Garbo's Hat), June Katz, Ming Lee, Ranee Lee, Moreen Meriden, Denzil Pinnock, Arlene Smith, Corry Sobol, Tena Palmer and Karen Young.

Meet Eleanor Collins - Canada's first lady of jazz and the first Black person in North America to host a nationally broadcast television series, "The Eleanor Show" which began in 1954.

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

The profile of female vocalists — throughout the jazz world, but particularly in Canada — was heightened dramatically by the widespread success of the Nanaimo, BC pianist and singer Diana Krall. Beginning with her shift from the Canadian label Justin Time to the iconic US jazz label Impulse! (owned by global conglomerate Universal Music Group) in 1995 and culminating in her Grammy and Juno Award-winning albums When I Look in Your Eyes (1999), The Look of Love (2001) and Live in Paris (2003), Krall became something of a style phenomenon, depicted by media outlets as a glamorous throwback to an earlier era. She has sold more than 15 million albums worldwide and achieved an unprecedented level of stardom for a contemporary jazz musician.

In Krall’s wake, both record labels and fans began to seek out other singers to embrace, increasing the attention paid to such Canadian female vocalists as Kellylee Evans, Nikki Yanovsky, Carol Welsman, Amy Cervini, Sophie Milman, Emilie-Claire Barlow, Laila Bialli, Molly Johnson and Jill Barber.

Krall’s influence was also seen in the popularity of two male singers: Michael Bublé — who, significantly, caught the attention of influential Canadian music business veterans Paul Anka and David Foster — and Matt Dusk. Although both actively pursued pop music, they also displayed the influence of jazz-based singers such as Tony Bennett and Frank Sinatra.

Canadian Musicians Abroad

The most celebrated Canadian-born musicians in jazz are Krall, Oscar Peterson, Paul Bley, Kenny Wheeler and the arranger-composer Gil Evans (born Ian Ernest Gilmore Green), who earned his standing through his innovative writing for the Claude Thornhill Orchestra (1941–42, 1946–48), and his collaborations with Miles Davis (on Miles Ahead, 1957; Porgy and Bess, 1958; Sketches of Spain, 1959) and Cannonball Adderley (on Pacific Standard Time, 1959).

Other Canadian-born musicians with notable careers in the US prior to the 1990s (many of whom, like Evans, left Canada while very young) include: Georgie Auld, a prominent swing-era (1930s and 1940s) tenor saxophonist; saxophonist Ralph Bowen; pianist Dave Bowman, who was active 1937–54 with many Dixieland greats in New York; vibraphonist Warren Chiasson; trumpeter Maynard Ferguson; bassist Hal Gaylor, who moved to New York in 1956 and subsequently worked with Chico Hamilton, Kai Winding, Paul Bley, Benny Goodman and others; pianist and arranger Buster Harding, who wrote for Teddy Wilson, Coleman Hawkins, Count Basie, Earl Hines and others ca. 1940; vibraphonist Hagood Hardy; pianist Lou Hooper; Kenny Kersey, who played for Red Allen, Andy Kirk, and 1946–49 for Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts; guitarist Peter Leitch; Al Lucas, bassist with Eddie Heywood (1943–46 and in the 1950s), Duke Ellington (1946) and Illinois Jacquet (1947–53); singer Anne Marie Moss; pianist Hartzell Strathdee (Tiny) Parham, who led bands in Chicago during the late 1920s; Bob Rudd, bassist with Noble Sissle, Lucky Thompson and others in Los Angeles in the 1940s, and in Montréal after 1950; trumpeters Herb Spanier and Fred Stone; and the flutist Alexander Zonjic, originally of Windsor, ON, and active in fusion jazz during the 1980s and early 1990s.

Other Canadian-born musicians worked in US big bands, among them the saxophonists Abe Aarons, Gordon Evans, Moe Koffman, Stuart MacKay and Don Palmer, the guitarists Arnold “Red” McGarvey and Danny Perri, and the trumpeters Chico Alvarez, Jimmy Reynolds and Al Stanwyck.

Canadian-born musicians who were active in British jazz included: Bob Burns, a saxophonist in big bands and studio orchestras after the 1950s; Diz Disley, a guitarist with Stéphane Grappelli during the 1970s and 1980s; Art Ellefson; Wally Fawkes, a clarinetist with post-war British “trad” bands (and who, like Diz Disley, was also a noted cartoonist, drawing “Flook” for the London Daily Mirror for more than 40 years); Max Goldberg, the “hot” trumpet soloist in British dance and jazz bands of the 1930s; trombonist Ian McDougall; John Warren of Montréal, a composer and saxophonist noted for Tales of the Algonquin (1971), whose big band toured widely in continental Europe in the 1970s; and Kenny Wheeler. The pianists Wray Downes and Milt Sealey, and the bassist Lloyd Thompson worked extensively in Europe in the mid-1950s; the Montréal pianist Fred Henke and the Toronto alto saxophonist Mike Segal were prominent there in the late 1980s.

Media

Jazz has had limited television exposure in Canada. There were Timex-sponsored programs on CBC TV in the 1950s and later CBC specials (including those devoted to Mingus and Ellington), CTV's Oscar Peterson Presents in 1974, the syndicated Peter Appleyard Presents (1977–80), and concert performances filmed during the 1980s at the FIJM. In 2000, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) issued a licence to Winnipeg-based Canwest Media to create CoolTV, a cable channel devoted to jazz music videos, concerts and films with jazz content. The station began broadcasting in 2003, but ceased operations in 2008.

On radio, CBC has produced a number of programs, many of which have featured specially recorded performances by Canadian musicians. These have included: 1010 Swing Club (1941–48) and its successor Jazz Unlimited (1948–65, with Dick MacDougal as host until his death in 1957, and then with Phil MacKellar); Jazz at Its Best (1950–76, with Ted Miller in Montréal); Jazz Workshop (1954–65), featuring bands from various cities; Jazz Canadiana (1965–71); Jazz Radio-Canada (1974–80), from Winnipeg with Mary Nelson and Lee Major; After Hours (1993–2001), from Winnipeg with Ross Porter; Jazz Beat (1983–2003), from Montréal with Katie Malloch; and Tonic, initially with Malloch and Tim Tamashiro alternating as hosts, and then just the latter after the former’s retirement in 2012. For many years CBC Montréal's Jazz en liberté, produced at the Ermitage, presented weekly half-hour concerts by the city's leading musicians.

In the private sector, Ted O'Reilly (CJRT-FM, Toronto), Ron Sweetman and Jacques Emond (both at CKCU-FM, Ottawa) and Len Dobbin (FM 96, Montréal) had long-running jazz radio programs. A commercial jazz station, CJAZ, flourished briefly in Vancouver during the early 1980s. In 2001, Toronto’s CJRT-FM adopted a full-time jazz format, broadcasting under the name JAZZ.FM91 and featuring a number of jazz musicians as hosts, including singers Heather Bambrick and Jaymz Bee, pianist Joe Sealy and guitarist Jeff Healey. From 2003 to 2007, Winnipeg-based Canwest Media operated CoolFM as an adjunct to its CoolTV cable TV station.

There have been five Canadian magazines devoted to jazz: Ad Lib (Toronto, 1944–47); Jazz Panorama (Toronto, 1946–48, edited by Helen McNamara and Marion Madghett, and briefly by Patrick Scott); Coda (Toronto, 1958–2009, founded by John Norris, and subsequently edited by Bill Smith, David Lee, Stuart Broomer, Daryl Angier and Andrew Scott); The Jazz Report (Toronto, 1987–2006, with the pianist Bill King as publisher and Greg Sutherland as editor); and Planet Jazz (Montréal, 1997–2003, edited by Carol Robertson). Various flyers, newsletters and other promotional ephemera have been published by jazz societies across the country — e.g., the Coastal Jazz and Blues Society's Looking Ahead, the Edmonton Jazz Society's Yardbird Suite Jazz, Jazz Winnipeg’s Dig! and the Jazz Association of Montréal's JAM Session.

Canadian journalists and/or critics working internationally in the field have included: Greg Buium (DownBeat), James Hale and Michael Chamberlain (DownBeat and Signal To Noise), and John Kelman (AllAboutJazz.com).

Within Canada, jazz journalists have included: Bob Smith (Vancouver Sun); Renee Doruyter (Vancouver’s The Province); Alex Varty (Vancouver’s Georgia Straight); James Adams and Roger Levesque (The Edmonton Journal); Peter Stevens (Windsor Star); Helen Palmer, Alex Barris, Patrick Scott, Jack Batten, Mark Miller, Stuart Broomer and J.D. Considine (The Globe and Mail); Peter Goddard, Val Clery and Geoff Chapman (The Toronto Star); Helen McNamara (Toronto’s Telegram); Lois Moody, Peter Hum and Doug Fischer (Ottawa Citizen); Len Dobbin, Juan Rodriguez and the journalist Paul Wells (Montréal Gazette); Gilles Archambault (Montréal’s Le Devoir); Alain Brunet (Montréal’s La Presse[AM14] ); Andrew Jones (Option, Jazziz); Marc Chenard (Coda, Jazz Podium, etc.); and Barry Tepperman (Coda, and Eric Dolphy, a Bio-Discography, Washington 1974, written with Vladimir Simosko). The US-based writers Gene Lees and Helen Oakley Dance (originally of Toronto) have also been active as critics and authors.

Recording Companies

Few commercial recordings of Canadian jazz musicians were made in Canada before 1980. Only Sackville Recordings (see also Coda) and its affiliated Onari label (see Bill Smith) concentrated on jazz, and Sackville's roster was largely comprised of US musicians. Other Canadian labels showed sporadic interest in jazz musicians during this period: Arc Records (Pat Riccio); Attic Records (Boss Brass, pianist Joel Shulman); Capitol Records (Lee Gagnon, vibraphonist Yvan Landry); Chateau (Trump Davidson); Canadian Talent Library Trust (CTL) (Norm Amadio, Ron Collier, and others); GRT (Moe Koffman, Doug Riley's Dr. Music); Hallmark Recordings (Mike White's Imperial Jazz Band); and Umbrella (Boss Brass and Humber College).

The New Jersey jazz label, PM, released seven LPs by Canadians 1975–79. Many other LPs in the late 1970s were financed and produced by the musicians themselves. The largest collection of recorded Canadian jazz to 1980 was that of RCI, whose approximately 500 albums included some 45 by jazz musicians. The CBC's LM recorded sound series also included jazz albums.

Several new record labels devoted to jazz or improvised music were introduced in the 1980s: Innovation (1981), Unisson (1985) and Unity (1988, see John MacLeod) in Toronto; Parkwood (1983) in Windsor; Justin Time (1983), Ambiances magnétiques (1985) and Amplitude (whose jazz releases began in 1989) in Montréal; and Victo (1987) from the Festival international de musique actuelle de Victoriaville. Also of significance was the interest in Canadian musicians shown by four California labels: Concord (see A & M); its affiliate The Jazz Alliance (introduced in 1991 under the direction of Phil Sheridan, formerly of Innovation); Nine Winds; and Music & Arts. Unity in particular allowed musicians to record free of pressures to conform with the commercial trends of the day.

On the other hand, RCI, the stalwart of jazz recording in Canada for many years, shuttered its music activities in 1991 by devoting the final release in its Anthology of Canadian Music series to jazz, drawing the 51 tracks from its own holdings and from commercial catalogues.

Beginning in the 1990s, the widespread adoption of digital technologies opened the door to many new labels, some of them sole proprietorships in service to a single musician or group. As traditional labels began to see their revenues decline due to digital downloading, jazz rosters at the major labels shrank, and a number of experienced record company executives started small, boutique labels. Some of these labels found international audiences through distribution licensing agreements or digital delivery. Among those that found some success were Songlines, Maximum Jazz, Drip Audio, Cellar Live, Barnyard Records, True North and Cornerstone.

Jazz Education

Lagging behind the growth of jazz education in the US by about a decade, formal post-secondary programs with a jazz focus in Canada were championed primarily by veteran band leader Phil Nimmons. Himself a product of classical music programs at the Julliard School and the Royal Conservatory of Music, Nimmons joined with pianist Oscar Peterson and bassist Ray Brown in 1960 to launch the short-lived Advanced School of Contemporary Music, which operated out of Peterson’s Toronto home.

In 1969, Nimmons took on the role of director of jazz studies at the University of New Brunswick, and the following year he and Peterson co-founded the summer jazz institute at the Banff School of Fine Arts (now the Banff Centre for the Arts; the program is now called the Banff International Workshop in Jazz and Creative Music). Nimmons subsequently began teaching jazz techniques at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music in 1973. Forty years later, he continued to be semi-active within the program as director emeritus of Jazz Studies, a position he assumed in 1991, shortly after the university began offering a degree in jazz. Nimmons also founded a jazz program at the University of Western Ontario (now Western University).

By the 1990s, several of Canada’s largest universities were offering jazz courses as part of a comprehensive music program, but Bachelor of Music degree programs in jazz did not become widespread until the 2000s. Driving this growth were a number of former community colleges that had their charters altered to become full-fledged universities, including Malaspina College (now Vancouver Island University) in Nanaimo, Grant MacEwan College (now MacEwan University) in Edmonton, and the Ryerson Institute of Technology (now Ryerson University) in Toronto. Still other colleges, including Capilano College in North Vancouver and Humber College in Toronto, were offering jazz diploma programs that emphasized the business and technical sides of developing a career in music.

By 2013, the jazz programs at the University of Manitoba, York University, the University of Toronto, Concordia University and McGill University (which offered the most prominent of the degree programs) were attracting students from many foreign countries, including the US, where tuition fees were generally much higher.

Jazz Venues and Festivals

Characteristically an urban music, jazz has had centres of support in most major Canadian cities. Its domain, beginning in the 1950s, has traditionally been the nightclub — e.g., The Cellar and the Glass Slipper in Vancouver; the Yardbird Suite (through several incarnations) in Edmonton; the Colonial and Town taverns, George's Spaghetti House, Bourbon Street, the Montréal Bistro, The Rex and Top O' The Senator in Toronto; Take Five and After Eight in Ottawa; Rockhead's Paradise, Café St-Michel, La Jazztek, Le Jazz Hot, the Rising Sun and Biddle's in Montréal; and the Hotel Clarendon in Québec City.

Support for live music across all genres dwindled following the rise of digital media in the late 1990s and early 2000s. By 2013, only Vancouver’s Cellar, Edmonton’s Yardbird Suite and Toronto’s The Rex remained from those that had flourished through 1990. The failure of existing establishments outpaced the introduction of new clubs, although notable newcomers include Jazz Bistro in Toronto, Upstairs and l’Astral in Montréal, and Largo in Québec City.

Summer jazz festivals began to flourish in the late 1970s, with events in Edmonton, Montréal and Ottawa launching within a year of one another. More joined the trend, with varying degrees of success. The most successful among them, the FIJM, became arguably the largest of its kind in the world within a decade of its founding. The eight largest festivals, stretching from Victoria to Halifax, took a major step forward in 2002 when they secured long-term funding (to 2014) from TD Bank Financial Group. This sponsorship permitted the festivals in smaller markets like Ottawa and Saskatoon to share headline artists with the festivals in Vancouver, Toronto and Montréal. Each of these festivals gave a substantial number of performance opportunities to Canadian artists, and created national touring opportunities and exposure to larger audiences. Smaller festivals also grew in less-populous communities, including Pender Harbour, BC, Guelph, ON, Rimouski, QC and Québec City.

A version of this entry originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom