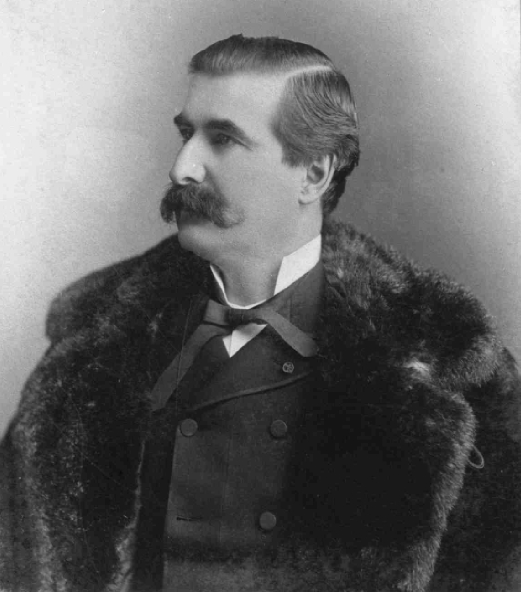

Tarte switched allegiances so often over the course of his career as a politician and journalist that his political rivals often referred to him by the unmistakable nickname of Judas Iscariot. That being said, his numerous and often abrupt political shifts were not opportunistic or cynical, but rather a political and intellectual response to an ever-changing era of tense, complex, and polarized social struggles.

Youth and Education

Tarte did his early schooling in Saint-Joseph-de-Lanoraie. He then continued his studies at the Collège de L’Assomption in 1860, but left after completing rhetoric and only half of his first year of philosophy (see Collège classique). He went on to apprentice as a notary clerk under Louis Archambeault and was admitted as a notary in 1871. He first worked in L’Assomption, and later for a few years in Saint-Lin des Laurentides. In 1872, he became the owner of the newspaper Les Laurentides and a contributor at La Gazette de Joliette. In October 1874, he became an associate editor at Le Canadien, which he bought a few months later, in June 1875, becoming partners with Louis-Georges Desjardins—the influential French Canadian newspaper’s editor-in-chief and a leading figure in the Québec Conservative Party.

Liberal-Conservative

As a Liberal-Conservative in the early 1870s, Tarte was opposed to the Catholic platform. His thinking was in line with moderate Conservative George-Étienne Cartier’s ideology, which was in favour of respecting the Church’s spiritual jurisdiction while limiting its involvement in politics. Cartier’s death in 1873 coincided with Tarte’s emergence as a political journalist, at a time when three social doctrines—liberalism, moderate conservatism, and conservative ultramontanism—were all up against each other. Tarte worked as an organizer to help solidify Hector-Louis Langevin’s newly acquired leadership of the Québec wing of the Conservative Party. He fought the Liberals to his left by painting them as anticlerical (particularly during the Guibord Affair), while fighting the ultramontanists to his right by undermining their platform with his nationalist editorials. His sharp mind and polemic passion made him the most respected journalist of his generation.

Ultramontane Shift

In the spring of 1875, Tarte suddenly began to lean toward ultramontanism and became one of its champions. From 1877 to 1881, he sat on the Conservative bench in the Québec National Assembly. During this time, he drew closer to Honoré Mercier’s Parti national—a coalition of Liberals and Conservatives who were also seeking the clergy’s support. To explain his sudden ideological shift, Tarte invoked his religious beliefs as well as the need to win over Québec voters (an approach that would be used again by the Castors in 1882). Knowing that a vote could go either way, Tarte began to consider that the Catholic Church should contribute its insights in politics. The Québec episcopate agreed with him, until the Vatican reestablished order through Pope Leo XIII’s 1885 encyclical, Immortale Dei, which called for the separation of duties between Church and State.

Liberal Shift

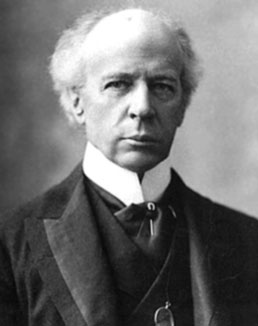

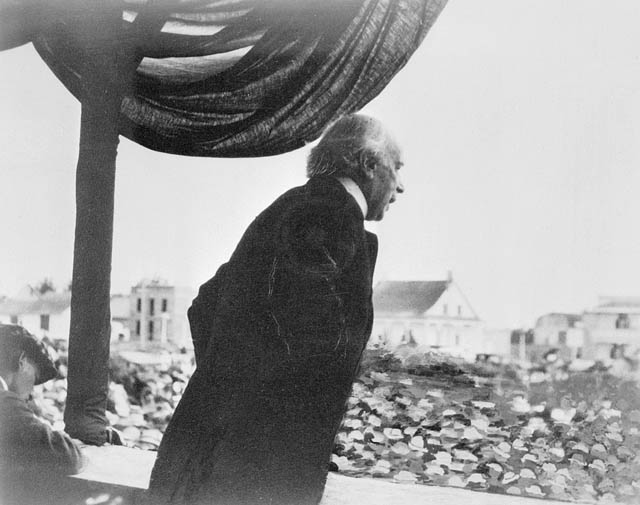

Once the Vatican settled the issue of the clergy’s interference in politics, Tarte returned to a more moderate platform. His finest hour arguably came between 1890 and 1891, when he exposed the McGreevy-Langevin scandal, first in Le Canadien,and then in the House of Commons, to which he was elected in 1891. The scandal forced his former political mentor Hector-Louis Langevin to resign from Cabinet and caused the Conservative Party to lose credibility—leaving Tarte sitting on the Liberal bench. The Manitoba schools question solidified his alliance with the Liberal Party, and Tarte’s success as a campaign manager contributed greatly to Wilfrid Laurier’s triumph in Québec in the election of 1896. Laurier immediately sent Tarte, a seasoned political defector, and Henri Bourassa, a young and successful ultramontane, to negotiate the status of Manitoba Catholic schools with Manitoba premierThomas Greenway and Justice Minister Clifford Sifton. Tarte and Bourassa would become two of the founders of the Laurier-Greenway compromise regarding the Manitoba schools question.

As minister of Public Works in Laurier’s government, Tarte sped up the redevelopment of the St. Lawrence Seaway in order to transport wheat from Western Canada to Europe. He oversaw the construction of the Soulanges Canal (a 23.5 km waterway connecting Lac Saint-François in the west to Lac Saint-Louis in the east) in order to replace the Beauharnois Canal, which was no longer deep enough to accommodate the size of modern ships. He committed resources to repair and widen ports, particularly the port of Montréal, and established a major Eastern Canadian shipyard in Sorel. He also launched public works in the Maritime provinces and in British Columbia. Tarte worked toward building a high-speed rail service between Liverpool, Nova Scotia, and Montréal, and built a railway through Drummondville, connecting the Intercolonial Railway to the Grand Trunk Railway.

Tarte’s position as minister of Public Works also fuelled his electioneering tendencies. He played favourites, strengthened relationships between the Liberals and the Montréal business community, and worked to bring about Laurier’s political progress in Québec. His opinions on controversial subjects were notorious and often contradictory, yet he was outspoken in his defence of them. He was a fierce supporter of British Imperialism, yet he strongly opposed the involvement of Canadian troops in the South African War in 1899. In 1900, he was severely criticized by the conservative press in Ontario for his remarks about Canadian independence. As a man of conviction rather than partisan obedience, who focused more on specific matters than broad political orientations, Tarte made an increasing number of enemies on both sides of the House of Commons.

Return to Conservatism

Finally, in 1902, Tarte’s campaign in favour of imperial economic unity and increased tariff protection lead Laurier to dismiss him, informing him that his new platform revealed a gap in the solidarity of the Liberal Party’s ministers. This marked the end of Tarte’s career in the federal government. He returned to his position as a Conservative campaign manager for a few by-elections. However, as a former Liberal minister, his paradoxical return to the Conservative bench caused controversy and he was quickly forced to give up politics altogether. He returned to journalism and, in a shocking turn of events, came out in support of Wilfrid Laurier’s stance on the North-West schools question in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Tarte died at age 59.

Main Works

Le clergé, ses droits, nos devoirs (1880)

La Prétendue Conférence: les périls de la souveraineté des provinces; l’autonomie canadienne est notre sauvegarde (1889)

Procès Mercier : les causes qui l’ont provoqué, quelques faits pour l’histoire (1892)

Les États-Unis au XXe siècle (1904)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom